They certainly didn't make it easy on themselves, but the Chicago Cubs, my favorite team, finally clinched the National League Central Division championship a couple hours ago. Now, my hands-on experience with baseball was limited to a brief and abysmal Little League career; nonetheless, honesty and the ghost of my North Sider grandfather compel me to trumpet my own not insignificant part in this championship. For it was on June 28th, on this very blog, that it was revealed that the Cubs' main competition down the stretch, the Milwaukee Brewers, were doomed.

If you recall, the discussion concerned Milwaukee's long-time classical music radio station WFMR, which the owners had decided, after more than 50 years, to switch to a—shudder—smooth-jazz format. At the time, I tried to caution against the dire consequences of such a move:

You Milwaukeeans should be more careful with your civic institutions: the Brewers are having their best season since 1982. The last thing they need is a curse.Did WFMR's management heed this warning and amend their easy-listening ways? No. The result? In the three months since, the then-first-place Brewers have gone a dismal 35-46, coughing up a 7½-game lead, surrendering the division to the Cubs. The Cubs, mind you. Anger not the gods of classical music.

(I should mention that I have no particular animus towards Brewers fans, who I remember as being an unusually discerning lot. The last time I saw the team was in 1998, when some brothers and sisters and I journeyed to old Miller Park for a Cubs-Brewers contest, hoping to fill up on bratwurst and beer before they tore the place down. This was late in the Sammy Sosa-Mark McGwire modern-medical-miracle home-run chase; needless to say, everyone was on their feet whenever Sosa came up to bat. But the highlight of the game was when Mickey Morandini, a veteran infielder who had come over to the Cubs from the Phillies, I think, beat out an infield single with a head-first slide. The crowd went bananas, demonstrating that, far from succumbing to the louche blandishments of the long ball, they remained connoisseurs of the true National League style of play.)

In order to promote the spread of Cub Fever (WARNING: Cub Fever is hazardous to your health), here's a few musical souvenirs of the last time the Cubs won the World Series—that would be 1908, thanks for asking—that I found deep within the online bowels of the Library of Congress.

First is "The Glory of the Cubs," dedicated to the "World's Champion Base Ball Team"—a somewhat pedestrian number (sample lyric: "That's why I'm going to sing this song to you / For I know it is true / The Cubs have won the champion game," etc., etc.) mainly notable for being a comparatively unsyncopated effort from Arthur Marshall, one of the early masters of ragtime. A protégé of Scott Joplin, Marshall wrote some of the best rags in the older, folk-like Missouri style, so I won't begrudge him cashing in on a topical novelty. Obligatory inside Cubs joke: hey, that bear on the cover throws a lot like Trachsel, doesn't he?

First is "The Glory of the Cubs," dedicated to the "World's Champion Base Ball Team"—a somewhat pedestrian number (sample lyric: "That's why I'm going to sing this song to you / For I know it is true / The Cubs have won the champion game," etc., etc.) mainly notable for being a comparatively unsyncopated effort from Arthur Marshall, one of the early masters of ragtime. A protégé of Scott Joplin, Marshall wrote some of the best rags in the older, folk-like Missouri style, so I won't begrudge him cashing in on a topical novelty. Obligatory inside Cubs joke: hey, that bear on the cover throws a lot like Trachsel, doesn't he? Next we have "Cubs on Parade," a march and two-step by the otherwise unknown H.R. Hempel. The publisher's name would seem to indicate that the piece originated from Chicago's significant German immigrant population, who provided the meat-packed foundation for that most sublime of culinary delights, the Chicago hot dog. This one is cool because the scan is actually of a full set of parts for a theatre-pit-sized orchestra. Plus, the bear winding up in the box there would be an absolutely righteous bit of tattoo flash, wouldn't it? If they go all the way, I'm seriously considering it.

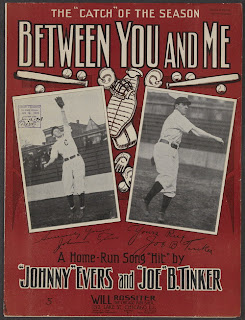

Next we have "Cubs on Parade," a march and two-step by the otherwise unknown H.R. Hempel. The publisher's name would seem to indicate that the piece originated from Chicago's significant German immigrant population, who provided the meat-packed foundation for that most sublime of culinary delights, the Chicago hot dog. This one is cool because the scan is actually of a full set of parts for a theatre-pit-sized orchestra. Plus, the bear winding up in the box there would be an absolutely righteous bit of tattoo flash, wouldn't it? If they go all the way, I'm seriously considering it. And finally, this oddity: "Between You and Me," a non-baseball-related love song credited to Johnny Evers and Joe Tinker, two-thirds of the most famous double-play combination in baseball history. Highly unlikely—Tinker and Evers hated each other, as a result of Evers abandoning his teammates in a hotel lobby and taking a cab for himself on one 1905 occasion. The two didn't speak to each other for the next 23 years, including the championship 1908 season. I think we chalk this one up to some enterprise on the part of the publisher, Will Rossiter (another significant name in the world of ragtime, by the way: at one time or another, he published works by most of the style's leading exponents).

And finally, this oddity: "Between You and Me," a non-baseball-related love song credited to Johnny Evers and Joe Tinker, two-thirds of the most famous double-play combination in baseball history. Highly unlikely—Tinker and Evers hated each other, as a result of Evers abandoning his teammates in a hotel lobby and taking a cab for himself on one 1905 occasion. The two didn't speak to each other for the next 23 years, including the championship 1908 season. I think we chalk this one up to some enterprise on the part of the publisher, Will Rossiter (another significant name in the world of ragtime, by the way: at one time or another, he published works by most of the style's leading exponents).Anyway, depending on how many tie-breakers the rest of the Senior Circuit needs to sort everything out, I should get about a week's reprieve before this team starts giving me daily angina again. Hey, for a Cub fan, that's like a lifetime.

Image at top from a 1932 Cubs program, lifted from this excellent site. Look, the Red Sox clinched, too!