Two of my greatest music score bargain finds have been Richard Strauss. Back in my Tanglewood days, a field trip to a used book store in northern Connecticut yielded a four-dollar Boosey vocal score of

Salome. And a few years back, I rescued this two-dollar treasure from a discard sale at the Boston Conservatory library.

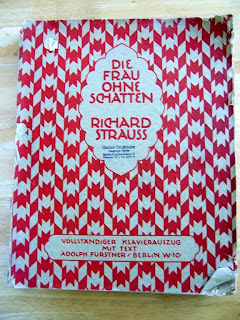

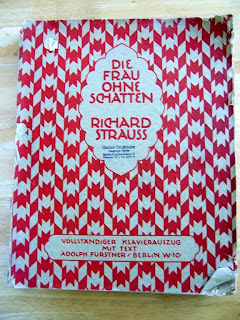

That's an original Fürstner piano-vocal score of

Die Frau ohne Schatten. I can see why the library was getting rid of it, as it's rather beat up: the spine is falling apart, the pages are brittle, most of the corners are cracked and disintegrating. For cheap score study, though, it's perfectly serviceable.

Actually, I'm not sure this particular copy ever any shelf time at all. Imagine my surprise when I opened it up at home and this came tumbling out:

The Staatsoper Berlin performed

Die Frau on June 22, 1940, and the previous owner of the score, a man named Gustav Grossmann, saw fit to hang on to the program. I'm not sure why—he doesn't appear among the personnel:

(Click on the image to enlarge. The only names I knew are Torsten Kalf and Walter Grossmann; no doubt opera buffs will recognize many more.) Grossmann did work for the Staatsoper, however. He stamped the score with his address:

Based on the markings in the score I'd guess he was either an assistant conductor or a

répétiteur. The only thing I've been able to learn about him is that he conducted the German premiere of Zemlinsky's opera

Der Kreidekreis in 1934, shortly before Zemlinsky left Germany forever. (The performance was repeatedly disrupted by a

claque of brownshirts.) No reference books, English or German, mention him. He must have survived the war—the score has pencilled notes regarding either a performance or a broadcast of the opera in 1959, conducted by Karl Böhm. (The singers mentioned seem to be the same as those on Böhm's 1955 Decca recording.)

I could probably find out more about him if I really tried; maybe someday I will. Right now, though, I don't

want to know more about him. For me, the power of this particular artifact lies in its mystery. I don't know what Grossmann's personal or professional connection with this particular piece was. I don't know what he did or didn't do during the war. I don't know why he kept the program—an innocent souvenir? A rueful reminder? Secret pride?

Most importantly, I don't know by what path this score, with its potent accessory, ended up in Boston, Massachusetts. And because I don't know, I'm forced to imagine, which inevitably leads to a consideration of what I would have done had I been in Grossmann's place, in any of the numerous scenarios, charged or benign, that could have transpired. It brings up the very real possibility that, in certain situations, I may not have been as heroic or courageous as I would like to imagine.

I've been revisiting the life and music of Anton Webern over the past few months. Webern's relationship to the Nazis was, to put it mildly, an unfortunate combination of naïveté, patriotism, and opportunism. He deplored the anti-Semitism, but was entranced by the strong German nationalism, the prospect of German culture once again taking the lead after the disaster of World War I. As his Jewish friends were forced into leave, Webern never could bring himself to denounce the Nazis. Maybe he thought that

Kristallnacht and the like was just a phase, that cooler heads would prevail, and everyone would come back. They never did, and the break with his former colleagues (particularly Schoenberg, who had been like a father) must have been distressing. One of the sadder episodes in Webern's life involves the solo piano

Variations, written in 1936: Webern dedicated the piece to the Jewish pianist Edward Steuermann as a token of friendship. Steuermann, shortly to flee Europe, never acknowledged the gift, disgusted by Webern's refusal to speak out.

Of course, Webern's pain is trivial compared with those who were exiled or who perished in the camps. But still, I get the sense that I would have rather liked Webern as a person, and I want to go back in time, shake him by the shoulders, and tell him,

convince him, that these people aren't who he thinks they are, that they're not going to change, and that he has to take a stand, that even remaining silent is a stain that he'll never be able to wash away. And then I wonder what someone from fifty years in the future would be shaking my shoulders about. One of the most amazing things about that 1940 program is that it contains absolutely no hint that there's a war on. In the face of even that epochal conflagration, the urge to maintain the façade of a normal, everyday life must have kept many people from refusing to recognize what was going on until it was too late. That's why I hang on to the program, to remind myself that the right thing to do isn't usually the convenient thing, that a path through life that avoids unpleasant obstacles is liable to lead one down dark, dead-end streets. Sunlight can burn, but the alternative is living in perpetual shadow.