Reviewing Collage New Music.

Boston Globe, January 31, 2008.

One historical note: music director David Hoose, introducing Berio's 1959 Differences, speculated that Monday's performance might have been the U.S. premiere, but the piece has been heard in America at least once before, in Philadelphia in 1972.

January 31, 2008

January 30, 2008

Eifersucht und Stolz

A brief moment of remembrance for Margaret Truman Daniels, who died this week at the age of 83. The daughter of Harry S Truman, before becoming a bestselling author, was a classical singer who ended up on the receiving end of one of the most famous bad reviews in history. "Miss Truman is a unique American phenomenon with a pleasant voice of little size and fair quality. She is extremely attractive on stage," wrote Washington Post critic Paul Hume in December of 1950. "Yet Miss Truman cannot sing very well. She is flat a good deal of the time—more so last night than at any time we have heard her in past years."

Then-President Truman didn't find that terribly illuminating, and fired off an intemperate response to Hume: "I've just read your lousy review of Margaret's concert. It seems to me that you are a frustrated old man who wishes he could have been successful," &c., &c. After Truman's letter became public, mail to the White House was reported to run 80-20 in the President's favor.

In that other 20 percent was a letter from Mr. and Mrs. William Banning of Connecticut:

Then-President Truman didn't find that terribly illuminating, and fired off an intemperate response to Hume: "I've just read your lousy review of Margaret's concert. It seems to me that you are a frustrated old man who wishes he could have been successful," &c., &c. After Truman's letter became public, mail to the White House was reported to run 80-20 in the President's favor.

In that other 20 percent was a letter from Mr. and Mrs. William Banning of Connecticut:

Mr. Truman,Enclosed with the letter was a Purple Heart. Truman kept the letter and the medal in his desk drawer for many years.

As you have been directly responsible for the loss of our son's life in Korea, you might just as well keep this emblem on display in your trophy room, as a memory of one of your historic deeds. One major regret at this time is that your daughter was not there to receive the same treatment as our son received in Korea.

On a rainy day, switching CDs, from a Handel opera to a Tippett one

Wring the Swan's Neck

Wring the swan's neck who with deceiving plumage

inscribes his whiteness on the azure stream;

he merely vaunts his grace and nothing feels

of nature's voice or the soul of things.

Every form eschew and every language

whose processes with deep life's inner rhythm

are out of harmony . . . and greatly worship

life, and let life understand your homage.

See the sapient owl who from Olympus

spreads his wings, leaving Athene's lap,

and stays his silent flight on yonder tree.

His grace is not the swan's, but his unquiet

pupil, boring into the gloom, interprets

the secret book of the nocturnal still.—Enrique González Martínez (1871-1952),

trans. Samuel Beckett

January 29, 2008

Manifold intake

Reviewing the Boston Modern Orchestra Project.

Boston Globe, January 29, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 29, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

January 28, 2008

Think of all you'll derive just by being alive

I ran across this line in a review this morning:

We all crave the illusion of a well-rounded life; we can't bear the thought of dying without the opportunity to give the prospect a conscious look in the eye. So we carve out the last ten, twenty years of an artist's life and file any and all works as "late style," giving a satisfying three-act structure to the meandering path of individual artistic evolution. Never mind that the works themselves often prove a disorderly leave-taking. Beethoven, possessor of the most famous late style in Western musical history, refused to play by the future's rules: those last string quartets, right up to the disorienting finale of the "Grosse Fuge," didn't sum up his legacy in a tidy way, but instead left his aesthetic estate in contentious probate for generations. The story of Brahms contemplating a Ragtime-influenced piece shortly before his death, as related in Robert Haven Schauffler's The Unknown Brahms, is, like much else in that entertaining volume, historically suspect, but its musical plausibility, in light of rhythmic ideas in Brahms' late instrumental works, at least demonstrates that even the historically-minded Brahms wasn't completely looking backwards at the end of his life.

Nonetheless, Brahms could be an exemplar of the stereotypical "late" style as well. Here's one of his most tender farewells, bringing down the curtain with an extraordinary empathetic depth (click to enlarge).

Those are the final two of the Variations on a Theme of Robert Schumann, op. 9. Brahms wrote it when he was 21. Most composers, in fact, develop the necessary technique for a sentimental deathbed scene pretty early on. Edward Elgar is a paragon of the valedictory, with his two later concerti, for violin and cello, held up as sterling examples. Elgar, though, had mastered the style by the time he was 40: both the "Enigma" Variations (age 42) and The Dream of Gerontius (age 43) have it in spades. Those works are hardly less elegiac because Elgar had the temerity to survive for another thirty years.

In the end (ha, ha), the whole perception of "late style" owes more to the imaginative needs of the audience than the creator. A couple of years ago, a series of lectures and compiled thoughts by the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said was published under the title On Late Style. Said admitted that his attraction to the subject was a personal one, having been diagnosed with leukemia in 1991. His chosen subjects were those creators, like Beethoven, whose late work was more of a challenge than a benediction. Reviewing the book in The New York Times, Edward Rothstein was miffed that Said seemed only interested in reinforcing his own intellectual biases.

The point is not that Rothstein is wrong—his characterization of late Beethoven is certainly more plausible than the AARP-centric reading of Brahms' 4th that sparked this ramble—but that the way he hears late Beethoven has far more to do with him than with Beethoven. And much of that is due to the coincidence of chronology: Rothstein's description of late Beethoven, for example, could just as easily describe Fidelio. But since we know that Fidelio is middle-period, not late-period, we don't look for intimations of mortality in it.

In fact, there's more than a few composers who did know that they were not long for the world, whether due to age or disease, and went out of their way to avoid the usual late-style trappings. Benjamin Britten, who had already produced a perfect farewell with Death in Venice, followed it up with the violent immediacy of Phaedra. Michael Tippett closed his final work, The Rose Lake, with a wink, the plop of a frog into the water. Verdi wrote Falstaff. Rossini set loose his "Sins of Old Age." Elliott Carter, who continues to cheat the actuarial tables at the age of 99, has become a fount of energetic, bracing, quirky works that defiantly insist on being encountered on their own terms, rather than through the prism of their composer's age. It's those of us who think we have a fair amount of time left that are concerned with stage-managing our exit; closer to the deadline, it seems that the best revenge is often just to keep on keeping on.

Similarly, though Brahms was nearing the "little blue pill" stage of his life when he wrote the Fourth Symphony, [the conductor] was determined that the composer come off as at the height of his musical virility and ready to wade into the trenches in the aesthetic wars between late-19th-century progressives and conservatives (Brahms being the reigning classicist).This displays two of our favorite qualities here at Soho the Dog HQ: it's 1) funny, and 2) wrong, but in an interesting way. Even if Brahms intended his last symphony as a conscious summing-up of his symphonic thinking, it's hardly a wistful farewell. (Besides, the man was only 52 at the time.) But the temptation to consider a composer's late output as related to some sort of dying of the light is near-irresistible.

We all crave the illusion of a well-rounded life; we can't bear the thought of dying without the opportunity to give the prospect a conscious look in the eye. So we carve out the last ten, twenty years of an artist's life and file any and all works as "late style," giving a satisfying three-act structure to the meandering path of individual artistic evolution. Never mind that the works themselves often prove a disorderly leave-taking. Beethoven, possessor of the most famous late style in Western musical history, refused to play by the future's rules: those last string quartets, right up to the disorienting finale of the "Grosse Fuge," didn't sum up his legacy in a tidy way, but instead left his aesthetic estate in contentious probate for generations. The story of Brahms contemplating a Ragtime-influenced piece shortly before his death, as related in Robert Haven Schauffler's The Unknown Brahms, is, like much else in that entertaining volume, historically suspect, but its musical plausibility, in light of rhythmic ideas in Brahms' late instrumental works, at least demonstrates that even the historically-minded Brahms wasn't completely looking backwards at the end of his life.

Nonetheless, Brahms could be an exemplar of the stereotypical "late" style as well. Here's one of his most tender farewells, bringing down the curtain with an extraordinary empathetic depth (click to enlarge).

Those are the final two of the Variations on a Theme of Robert Schumann, op. 9. Brahms wrote it when he was 21. Most composers, in fact, develop the necessary technique for a sentimental deathbed scene pretty early on. Edward Elgar is a paragon of the valedictory, with his two later concerti, for violin and cello, held up as sterling examples. Elgar, though, had mastered the style by the time he was 40: both the "Enigma" Variations (age 42) and The Dream of Gerontius (age 43) have it in spades. Those works are hardly less elegiac because Elgar had the temerity to survive for another thirty years.

In the end (ha, ha), the whole perception of "late style" owes more to the imaginative needs of the audience than the creator. A couple of years ago, a series of lectures and compiled thoughts by the late Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said was published under the title On Late Style. Said admitted that his attraction to the subject was a personal one, having been diagnosed with leukemia in 1991. His chosen subjects were those creators, like Beethoven, whose late work was more of a challenge than a benediction. Reviewing the book in The New York Times, Edward Rothstein was miffed that Said seemed only interested in reinforcing his own intellectual biases.

But the reason we care about these works is not that they express irreconcilable contradictions or exile. Rather, each constructs an alternative universe in which something is actually being understood about our world: some things are rejected, some are accepted, some are greeted with horror, some with resignation. Beethoven's late music, for example, embraces incongruities because — we are convinced — that is precisely what it means to see the world whole. There is accumulated knowledge here: recognition and reconciliation, not just "intransigence" or "unresolved contradiction."But that analysis is an expression of Rothstein's bias: he no more knows what Beethoven was really thinking than Said, or you, or I do. It's his own wish for a certain all-knowing equanimity in the face of death that causes him to read that equanimity into the music. Later, Rothstein takes to task Said's analysis of Jean Genet, who, like more than a few aging artists at the end of their alotted span, was inspired to adopt the revolutionary ideals of a younger generation. Rothstein lays out a series of rhetorical questions:

But wouldn't a "late style" have some sense of irony about this romanticization of violence? Or some notion about precisely what these light, sparkling, open figures were intending? Wouldn't it require being more attuned to the precise character of the contradictions so warmly embraced? Doesn't late style require some scrupulous self-reflection, some sense of how earlier perceptions might themselves require revisiting and revising? Wouldn't something similar have even helped Said's own late style?Answers: not necessarily; not necessarily; not necessarily; not necessarily; but then it wouldn't have been Said's style. Rothstein is unwittingly painting a portrait of how he would like to be remembered: a thoughtful realist, sympathetically but firmly dismantling the folly of youth with hard-won wisdom. Said, who spent his own career delineating the ways in which scholars projected their own worldview into their supposedly dispassionate analyses, would have appreciated the irony.

The point is not that Rothstein is wrong—his characterization of late Beethoven is certainly more plausible than the AARP-centric reading of Brahms' 4th that sparked this ramble—but that the way he hears late Beethoven has far more to do with him than with Beethoven. And much of that is due to the coincidence of chronology: Rothstein's description of late Beethoven, for example, could just as easily describe Fidelio. But since we know that Fidelio is middle-period, not late-period, we don't look for intimations of mortality in it.

In fact, there's more than a few composers who did know that they were not long for the world, whether due to age or disease, and went out of their way to avoid the usual late-style trappings. Benjamin Britten, who had already produced a perfect farewell with Death in Venice, followed it up with the violent immediacy of Phaedra. Michael Tippett closed his final work, The Rose Lake, with a wink, the plop of a frog into the water. Verdi wrote Falstaff. Rossini set loose his "Sins of Old Age." Elliott Carter, who continues to cheat the actuarial tables at the age of 99, has become a fount of energetic, bracing, quirky works that defiantly insist on being encountered on their own terms, rather than through the prism of their composer's age. It's those of us who think we have a fair amount of time left that are concerned with stage-managing our exit; closer to the deadline, it seems that the best revenge is often just to keep on keeping on.

January 26, 2008

Horseplay

Off-topic for the weekend, a gem from my e-mail spam folder. Subject line: "A Token of My Love." The purported sender: "doncorleone24."

January 24, 2008

Searching for Love

Cultural economics has come a long way since Baumol and Bowen first started poking around, but the fact remains that it still revolves around money—the delicate dance of legal tender among producers, sellers, and buyers. More so than other goods, there's almost always a disconnect between the price of a work of art and its value, and traditional market economies are notoriously slow and inefficient at minding that gap; while the art market as a whole can give a reasonably predictable return on investment, the market for individual works or categories of art can be dauntingly volatile. And that's the plastic arts, something you can take home and display. Music? Even cloudier.

So here's a thought experiment: what if, instead of cash, one considered curiosity as the main currency of culture? Curiosity drives cultural consumption. We keep looking until we find what we like, or what we think we like—maybe we come across a style or repertoire that seems to be enough of what we like that we consider any further search too expensive, in terms of curiosity. In this scheme, art that is harder to find is more "expensive"—and consumers who are more curious spend more. (Note that what is about to follow is laughable as economics—how do you quantify curiosity? Think of it more as a metaphor on steroids.)

In terms of curiosity, popular culture is very cheap indeed—almost free, in fact. (Try to resist applying favorable or unfavorable connotations to "cheap" and "expensive" for this one.) Popular culture comes to you via the mass media. If that's what you like, or what you decide you like, you haven't had to spend very much curiosity at all. Whereas, if what you really like is avant-garde tape-manipulation music from early-1970s Scandanavia, but you don't know that yet, you're going to have to spend a considerable amount of curiosity to find it.

The interesting thing about this goofy scheme is how, under it, one would interpret the impact of the Internet. You could argue that, back in the pre-tubes dark ages, music was actually cheaper in curiosity terms, but there was a greater chance of having to settle for less than you were prepared to "pay" for. There was whatever was being pumped out over the mass media, but beyond that, you were limited to whatever record companies were willing to record and distribute, or whatever happened to be performed near where you lived. For recordings, once you stepped into a record store, the curiosity price of anything that happened to be in the store would be pretty much the same, but if it wasn't there, you weren't very likely to find it without a huge jump in curiosity price. Live performance would be so balkanized by geography—New York? cheap; central Nebraska? not so cheap—that comparing curiosity spending would be almost apples to oranges. (Hopping on the subway=low curiosity price; moving to New York=high curiosity price.)

With the Internet, though, all music (or at least enough information to know whether it's what you want) is available, theoretically with near-immediacy—that is, if you know where to look, or, more probably, you have the time and curiosity to sift through the much wider array on offer. Has this made music cheaper or pricier in terms of curiosity? Back in the Reagan era, sifting through the bins at my local record store would take me, at most, a couple hours. A couple hours on the Internet, and I've barely scratched the surface. With greater variety comes greater investment of time, effort, judgement. (It's the same reason I can shop for shoes exponentially faster than my lovely wife, since, at size 14, my selection is usually limited to one or two pair.) Has the increased digital availability of culture, paradoxically, raised its curiosity price across the board?

As the economist Alfred Marshall once pointed out, artistic styles don't usually have diminishing marginal utility—once we find what we like, we can like the same thing pretty much forever. The thing is, most people, even music lovers, are going to decide they like some kind of music and stop spending their curiosity earlier than than those of us sufficiently obsessed with the stuff to blog about it. When curiosity prices were fixed and relatively low (i.e., record store), the chance of a given outlay of curiosity leading into jazz, classical, world music, showtunes—basically anything not served up free by the mass media—was not all that variable, once you walked in the door. (The downside? Opportunity costs, that is, the amount you give up by making a decision one way or another, were relatively high.) If curiosity prices have become higher with the advent of the Internet, the chance of a given outlay leading to a specific category is just that: a chance. It's much more of a crapshoot. There's a greater chance of stumbling on something you didn't expect, but an equal or greater chance of missing what you really want—or giving up before you find it. It all depends on how hard you want to look.

So in terms of the curiosity expended to find it, the initial price barrier to culture has gone way down, but the average price of the wanted cultural experience has, perhaps, gone up. Inflation, in other words. Is it a valid trade-off? I think so: since the resources aren't scarce—it's all out there somewhere, at the click of a mouse—opportunity costs go down. For now, the increased opportunity to at least stumble on what isn't expected seems to be raising the tide for all kinds of boats. The question is whether the way people are able to search for music on the Internet will evolve towards a more sophisticated, Pandora-like guided journey, or whether the old corporate categories will re-assert themselves, leading to more dead-end or prematurely stifled spending of curiosity.

The former, most likely. Here's why, although I admit it's a bit of a stretch. The previous way of buying and selling music was based on a certain assumed valuation of curiosity. If that curiosity is going through inflation? All bets are off. Inflation has the power to mutate economic systems at the genetic level. It's why central banks throughout the Capitalist Era have never stopped worrying about it. Here's how John Maynard Keynes put it, in The Economic Consequences of the Peace:

So here's a thought experiment: what if, instead of cash, one considered curiosity as the main currency of culture? Curiosity drives cultural consumption. We keep looking until we find what we like, or what we think we like—maybe we come across a style or repertoire that seems to be enough of what we like that we consider any further search too expensive, in terms of curiosity. In this scheme, art that is harder to find is more "expensive"—and consumers who are more curious spend more. (Note that what is about to follow is laughable as economics—how do you quantify curiosity? Think of it more as a metaphor on steroids.)

In terms of curiosity, popular culture is very cheap indeed—almost free, in fact. (Try to resist applying favorable or unfavorable connotations to "cheap" and "expensive" for this one.) Popular culture comes to you via the mass media. If that's what you like, or what you decide you like, you haven't had to spend very much curiosity at all. Whereas, if what you really like is avant-garde tape-manipulation music from early-1970s Scandanavia, but you don't know that yet, you're going to have to spend a considerable amount of curiosity to find it.

The interesting thing about this goofy scheme is how, under it, one would interpret the impact of the Internet. You could argue that, back in the pre-tubes dark ages, music was actually cheaper in curiosity terms, but there was a greater chance of having to settle for less than you were prepared to "pay" for. There was whatever was being pumped out over the mass media, but beyond that, you were limited to whatever record companies were willing to record and distribute, or whatever happened to be performed near where you lived. For recordings, once you stepped into a record store, the curiosity price of anything that happened to be in the store would be pretty much the same, but if it wasn't there, you weren't very likely to find it without a huge jump in curiosity price. Live performance would be so balkanized by geography—New York? cheap; central Nebraska? not so cheap—that comparing curiosity spending would be almost apples to oranges. (Hopping on the subway=low curiosity price; moving to New York=high curiosity price.)

With the Internet, though, all music (or at least enough information to know whether it's what you want) is available, theoretically with near-immediacy—that is, if you know where to look, or, more probably, you have the time and curiosity to sift through the much wider array on offer. Has this made music cheaper or pricier in terms of curiosity? Back in the Reagan era, sifting through the bins at my local record store would take me, at most, a couple hours. A couple hours on the Internet, and I've barely scratched the surface. With greater variety comes greater investment of time, effort, judgement. (It's the same reason I can shop for shoes exponentially faster than my lovely wife, since, at size 14, my selection is usually limited to one or two pair.) Has the increased digital availability of culture, paradoxically, raised its curiosity price across the board?

As the economist Alfred Marshall once pointed out, artistic styles don't usually have diminishing marginal utility—once we find what we like, we can like the same thing pretty much forever. The thing is, most people, even music lovers, are going to decide they like some kind of music and stop spending their curiosity earlier than than those of us sufficiently obsessed with the stuff to blog about it. When curiosity prices were fixed and relatively low (i.e., record store), the chance of a given outlay of curiosity leading into jazz, classical, world music, showtunes—basically anything not served up free by the mass media—was not all that variable, once you walked in the door. (The downside? Opportunity costs, that is, the amount you give up by making a decision one way or another, were relatively high.) If curiosity prices have become higher with the advent of the Internet, the chance of a given outlay leading to a specific category is just that: a chance. It's much more of a crapshoot. There's a greater chance of stumbling on something you didn't expect, but an equal or greater chance of missing what you really want—or giving up before you find it. It all depends on how hard you want to look.

So in terms of the curiosity expended to find it, the initial price barrier to culture has gone way down, but the average price of the wanted cultural experience has, perhaps, gone up. Inflation, in other words. Is it a valid trade-off? I think so: since the resources aren't scarce—it's all out there somewhere, at the click of a mouse—opportunity costs go down. For now, the increased opportunity to at least stumble on what isn't expected seems to be raising the tide for all kinds of boats. The question is whether the way people are able to search for music on the Internet will evolve towards a more sophisticated, Pandora-like guided journey, or whether the old corporate categories will re-assert themselves, leading to more dead-end or prematurely stifled spending of curiosity.

The former, most likely. Here's why, although I admit it's a bit of a stretch. The previous way of buying and selling music was based on a certain assumed valuation of curiosity. If that curiosity is going through inflation? All bets are off. Inflation has the power to mutate economic systems at the genetic level. It's why central banks throughout the Capitalist Era have never stopped worrying about it. Here's how John Maynard Keynes put it, in The Economic Consequences of the Peace:

Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency.... Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.I wonder if the Internet is really what changed things—or if a decrease in available musical variety in the years just before the Internet caused a change in the way people allocated and expended their curiosity, and the resulting, imperceptible disintegration of the traditional recording industry was already underway when the Web came along to accelerate it. Most revolutions, after all, are as much a culmination of historical trends as an instigator of them. That causality is probably a stretch, too, but how else do you explain how the record companies were caught so flat-footed? Corporate stupidity is hardly rare, but when an entire industry is still playing catch-up a dozen years on, deeper shifts become more plausible. Did the recording industry shoot themselves in the foot just before the Internet came along to stomp on it? Curious.

January 22, 2008

When in Rome

Reviewing Teatro Lirico d'Europa's Tosca.

Boston Globe, January 22, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 22, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

Deep covers

One big difference between books and sheet music: nowadays, any reasonably experienced musician can identify the publisher of a piece of sheet music from about twenty feet away. The pale-green-plus-giant-composer-name design of Peters; the yellowish-beige-sans-serif-small-caps of G. Schirmer; the flush-right-lower-case-bold-black-and-white of Universal Edition, etc., etc. Even a Dover score, with its clip-art-plus-white-text aesthetic, can usually be spotted on a podium stand from the second balcony.

Which is why I still love hunting down antique scores. As my lovely wife will confirm with a roll of her eyes, I love old stuff, and that includes sheet music. Popular sheet music, of course, is extremely collectible on account of eye-catching covers, but there was a time when classical wasn't that far behind. Here's five favorites I pulled from my shelves.

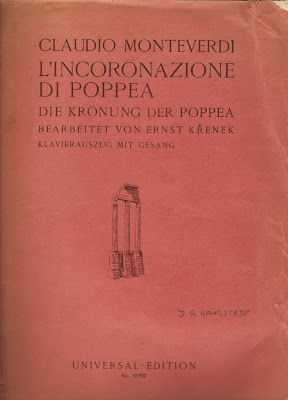

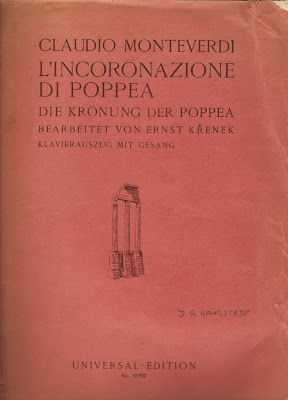

Monteverdi/Krenek: L'Incoronazione di Poppea (Universal Edition, 1937). Pure neo-classicism, by way of Napoleonic archeological surveys. I picked this up at a Boston Conservatory library sale; from the library of Ingrid Kahrstedt Brainard, the early dance historian, which is pretty cool.

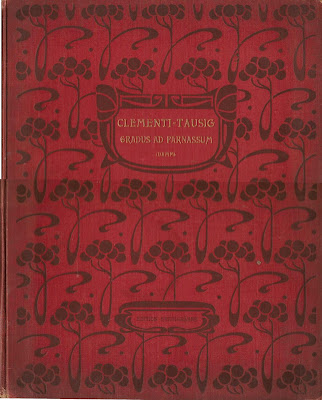

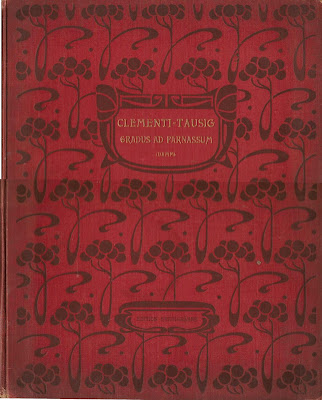

Clementi/Tausig: Gradus ad Parnassum, ed. Gustav Damm (Steingräber-Verlag, n.d.). No date, but I'm guessing sometime before absinthe became illegal. I can imagine Alma Mahler wallpapering her bathroom with that pattern.

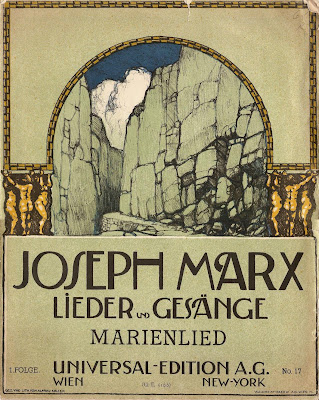

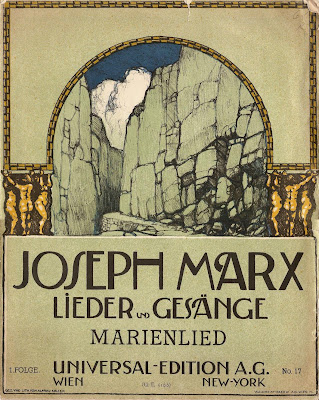

Joseph Marx: Marienlied (Universal Edition, 1925). The lithograph is by Alfred Keller. I don't know what Rubenesque nudes holding up a proscenium arch in front of craggy landscape has to do with the song, and I don't care.

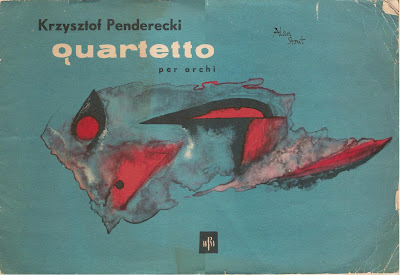

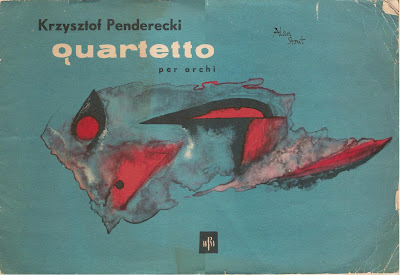

Penderecki: Quartetto per archi (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1963). A classic piece of abstract expressionism from the Polish state music publisher, who opted for these sorts of far-out covers quite a bit. Purchased at a used-book sale in Chicago many years ago—the previous owner was composer Alan Stout, which I initially thought to be an amazing coincidence, until I realized that there were probably at most a couple dozen copies of this in all of Chicago.

Janáček: The Cunning Little Vixen (Universal Edition, 1924 [reprint]). This is such a fantastic cover that it's criminal there's no artist credit. (And I looked—it does seem to be the same artist who did the cover for UE's edition of Krenek's Jonny Spielt Auf). It's been years and years since I saw an album cover or movie poster that good. In some ways (not many, but some), the old days were better.

Which is why I still love hunting down antique scores. As my lovely wife will confirm with a roll of her eyes, I love old stuff, and that includes sheet music. Popular sheet music, of course, is extremely collectible on account of eye-catching covers, but there was a time when classical wasn't that far behind. Here's five favorites I pulled from my shelves.

Monteverdi/Krenek: L'Incoronazione di Poppea (Universal Edition, 1937). Pure neo-classicism, by way of Napoleonic archeological surveys. I picked this up at a Boston Conservatory library sale; from the library of Ingrid Kahrstedt Brainard, the early dance historian, which is pretty cool.

Clementi/Tausig: Gradus ad Parnassum, ed. Gustav Damm (Steingräber-Verlag, n.d.). No date, but I'm guessing sometime before absinthe became illegal. I can imagine Alma Mahler wallpapering her bathroom with that pattern.

Joseph Marx: Marienlied (Universal Edition, 1925). The lithograph is by Alfred Keller. I don't know what Rubenesque nudes holding up a proscenium arch in front of craggy landscape has to do with the song, and I don't care.

Penderecki: Quartetto per archi (Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1963). A classic piece of abstract expressionism from the Polish state music publisher, who opted for these sorts of far-out covers quite a bit. Purchased at a used-book sale in Chicago many years ago—the previous owner was composer Alan Stout, which I initially thought to be an amazing coincidence, until I realized that there were probably at most a couple dozen copies of this in all of Chicago.

Janáček: The Cunning Little Vixen (Universal Edition, 1924 [reprint]). This is such a fantastic cover that it's criminal there's no artist credit. (And I looked—it does seem to be the same artist who did the cover for UE's edition of Krenek's Jonny Spielt Auf). It's been years and years since I saw an album cover or movie poster that good. In some ways (not many, but some), the old days were better.

January 21, 2008

Trying to get home

It's Martin Luther King Jr. Day here in the United States. Given the persistence of human nature, the quotation I posted last year will no doubt remain apt for many years to come.

Counter service

Reviewing David Daniels.

Boston Globe, January 21, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 21, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

January 19, 2008

The undiscover'd country

A composer's faith rewarded. On Elgar and The Dream of Gerontius.

Boston Globe, January 20, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 20, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

January 18, 2008

You probably think this song is about you

The scholars of the week here at Soho the Dog HQ are psychologists Brian P. O'Connor and Jamie Dyce, of Lakehead University and Concordia University, respectively. Back when both were at Lakehead, they wanted to test a particular model of self-perception called the looking-glass self chain. Previous tests of the model had focused on the role of the opinions and perceived opinions of peers and colleagues; O'Connor and Dyce were looking to build on more recent work that had factored in the opinions of significant others. What they needed was a situation in which both sets of opinions would be in play.

Actual appraisals: what other people really think of you. Feedback given: what other people tell you they think of you. Feedback received: what you hear when other people tell you what they think of you. Reflected appraisals: what you think other people really think of you. Self-appraisal: what you think of yourself.

Two particular criticisms of the looking-glass self chain could then be evaluated. O'Connor and Dyce again:

O'Connor and Dyce took the opportunity to have the same 171 musicians complete Inter-personal Adjective Scale-Big Five (IASR-B5) measures of personality. Their findings?

Felson (1989) found that the actual and reflected appraisals of parents affected childrens' self-appraisals of academic and athletic ability, and to a lesser degree self-appraisals of physical attractiveness and popularity. Edwards and Klockars (1981) and Schafer and Keith (1985) exmined the perceptions of marriage partners and found significant relationships among actual, reflected, and self-appraisals. One purpose of our study was to replicate these findings using a very different sample of subjects: musicians in bar bands.As they reported in their 1993 study "Appraisals of Musical Ability in Bar Bands: Identifying the Weak Link in the Looking-Glass Self Chain" (published in Basic and Applied Social Psychology), O'Connor and Dyce surveyed 171 bar band musicians, having them rate, on a scale of 1 to 5, their own perceptions of all five steps in the looking-glass self chain:

Two particular criticisms of the looking-glass self chain could then be evaluated. O'Connor and Dyce again:

The communication-barriers hypothesis suggests that the weakest link is between actual appraisals and feedback given by significant others. People do not communicate their true perceptions to self-appraisers. In contrast, the cognitive-processes hypothesis suggests that the weak link is between feedback given by significant others and individuals' perception of that feedback. Information is lost on the way from sender to receiver.Any wagers? The researchers found that musicians, in fact, say what they think—but only hear what they want to.

Of particular interest in this study is the finding that the correlation between actual appraisals and feedback given (r =.62) and the correlation between feedback given and feedback received (r =.38) were both significant, but the actual appraisals-feedback given correlation was significantly stronger according to the formula for comparing dependent correlations recommended by Cohen and Cohen (1983, p. 56), t =3.61, p <.01, two-tailed. This indicates that the weakest link in the looking-glass self chain is between feedback given and feedback received, and not between actual appraisals and feedback given.Brutally blunt to others, stubbornly pleased with ourselves—sounds like most musicians.

O'Connor and Dyce took the opportunity to have the same 171 musicians complete Inter-personal Adjective Scale-Big Five (IASR-B5) measures of personality. Their findings?

The results suggest that [popular] musicians tend to be more arrogant, dominant, extroverted, open to experience and neurotic than university males. However, no significant differences were found among singers, guitarists, bass players and drummers.Just remember, if you argue with the results, you're further undermining the weak link in the looking-glass self chain. Those scientists—always thinking two moves ahead.

January 16, 2008

Picture-in-picture

Reviewing the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra.

Boston Globe, January 16, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 16, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

January 15, 2008

Jetzt immer Schnee

High 60s last week, a foot of snow this week. Here's how screwy the climate has been in New England this winter: while Critic-at-Large Moe and I were on this hike, we saw a mosquito fly by.

January 14, 2008

Someone to watch over me

Today's fun fact:

The Malkin Conservatory seems like a great topic for study, incidentally—it was only in existence for a decade, yet attracted such students and faculty as Schoenberg, Roger Sessions, Ernst Krenek, Nicolas Slonimsky, Conlon Nancarrow, Harold Shapero, and Arthur Fiedler. Imagine those convocations.

*Update (1/15): Or had he? A murky minor mystery of history—see comments.

Mrs. A. Lincoln Filene of Boston, music patron and philanthropist, and George Gershwin, American composer, are among those who have contributed towards scholarships with Arnold Schönberg, internationally famous musician and teacher, who will come here next month to teach at the Malkin Conservatory of Music in Boston. Schönberg is an exile from Germany.From a September 26, 1933 New York Times report. (That's Filene as in Filene's Basement, by the way.) Most of us Schoenberg fans know of his one-year stint at the Malkin Conservatory, before he left for California on the grounds of, depending what you read, health or disappointingly poor students (probably both). I'd even run across mention of Gershwin's support. But his remarks were new to me.

Gershwin's gift to the Schönberg scholarship fund was made as soon as he was informed of the great modernist's coming to the United States. Himself an exponent of the use of the modern, native idiom in composition, Gershwin was delighted to come to the aid of the man who has been one of the most daring musical experimenters of our time.Time magazine also covered Schoenberg's arrival.

"America may well consider herself fortunate," Gershwin said yesterday, "to have so distinguished a composer and teacher choose this country for his home. It is my sincere hope that Schönberg will stay a long, long time. His teaching at Boston cannot fail to stimulate and better musical expression here.

"Furthermore, it will once more prove to Germany our intense disapproval of its tyranny and bigotry. Germany's loss will be this country's musical gain."

He has upset conservative concertgoers more than any other modern composer. Philadelphia and New York have not forgotten the harrowing chromatics in Die Glückliche Hand, which Leopold Stokowski gave three years ago. The much talked-of Wozzeck, which the Philadelphia Grand Opera Company put on, is a Schönberg stepchild. His pupil Alban Berg wrote it.It's interesting that at this point, Gershwin had not actually met Schoenberg;* most likely Gershwin's enthusiasm stemmed from his 1928 meeting with Alban Berg in Vienna. Also note Schoenberg's high reputation in the press—even in Time, which doesn't think much of the music—contrasting with the prophet-in-the-wilderness perception of Schoenberg's arrival on these shores (a perception cultivated not a little by Schoenberg himself). Gershwin's comments, assuming they reflect his thinking (the quote does sound a bit like a press release), show him on the cutting edge for 1933, both culturally and politically; this is, after all, only a few months after the Reichstag fire, and still prior Hindenburg's death.

Three weeks ago Arnold Schönberg landed in the U. S., surprised everyone by being a shy, mild little man not a bit fierce or radical in his comments on music or German politics....

...

Critics took the stand that in his effort to develop something new Schönberg had lost his real inspiration and become a hard-headed mathematician.... But no one has denied his genius as a teacher. In Europe where he had the facilities he took his pupils into his home to live, helped them study Bach and Beethoven, then let them write the kind of music which came naturally to them. His U. S. pupils will have to go through the same fundamental training. The one thing he will not encourage is imitation Schönberg.

The Malkin Conservatory seems like a great topic for study, incidentally—it was only in existence for a decade, yet attracted such students and faculty as Schoenberg, Roger Sessions, Ernst Krenek, Nicolas Slonimsky, Conlon Nancarrow, Harold Shapero, and Arthur Fiedler. Imagine those convocations.

*Update (1/15): Or had he? A murky minor mystery of history—see comments.

January 11, 2008

You Don't Know Me

Today's top story is this very odd one out of the Czech Republic, via Norway. Czech composer Barbara Skrlova was arrested in Norway after impersonating a 13-year-old boy named "Adam." As it turns out, Skrlova has been wanted in her home country as a witness in a child-abuse case.

In other, lighter news, it appears that Bollywood has found its own Jay Greenberg.

For his part, a film musical has inspired Norman Lebrecht to linguistic invention:

Finally, fellow church music director Frank Pesci points out this MSN story in which the seventh-fastest growing salary in America is revealed to be that paid to "music directors and composers". (We're tied with agricultural inspectors! We're at least as important to the economy as detecting whether that turnip is really organic or not!) And I see by the average that some of you bourgeois pigs out there are making 50 grand a year at this. No kidding! Next time I'm out with other composers, they're buying—and I'm ordering good beer.

Norwegian police detained Skrlova on January 5 in the northern town of Tromso thinking that they had finally located a 13-year-old runaway Czech boy named Adam, whom they believed was being abused.Skrlova had apparently previously impersonated a teenage girl named "Anna," who had been adopted by a woman named Klara Mauerova. Back in the spring, that deception was unmasked when Mauerova and her sister were arrested under bizarre circumstances for child-abuse; authorities suspect the sisters, and possibly Skrlova, are members of a breakaway faction of the Grail Movement, dedicated to the individualist teachings of Oskar Ernst Bernhardt, a.k.a. Abd-ru-shin, a German mystic who died in 1941. (A representative of the Grail Movement in the Czech Republic stated that the movement had cut ties with the sisters "after they added to the Grail Message with their own imaginings and fantasies".) At this point, no one is quite sure whether Skrlova was one of the abusers or one of the abused. The case is being called "one of the strangest in Czech criminal history".

At the time, police had no inclination that they had ended an eight-month-long manhunt for a 33-year-old crown witness in a bizarre and intricate child-abuse case in a distant Central European country.

Skrlova, who was escorted to the Czech Republic and placed in custody earlier this week, had pretended to be Adam for four months. She even went to school in the Norwegian capital Oslo under her new identity.

In other, lighter news, it appears that Bollywood has found its own Jay Greenberg.

A ninth standard student from Kerala is all set to achieve a rare distinction by becoming the music composer for a feature film at the age of 13 years.This is probably actually a bigger deal than Greenberg—Bollywood music composers are celebrities in their own right, rivaling the films' stars in both billing and tabloid attention.

"I am very happy to get a chance to compose songs in the Malayalam movie 'Plavilla Police'," a jubilant Ramatheerathan told PTI after the 'pooja' for recording of songs at a studio here.

For his part, a film musical has inspired Norman Lebrecht to linguistic invention:

Sweeney Todd the musical is, of course, famously indestructible. I have seen it raise the roof at the Royal Opera House and in half-rehearsed college productions, with full choreography and in John Doyle’s compact version for nine singing instrumentalists. Sweeney never fails. Getting it onto screen, though, was fraught with ibstgacles.Fraught with WAIT A MINUTE I DON'T THINK THOSE LETTERS ARE SUPPOSED TO BE ALL NEXT TO EACH OTHER THAT WAY. I like it! It's like visual onomatopoeia—you're reading along, and then your eyes stumble over ibstgacles like, well, an insurmountable ibstgacle. Update (1/11): alas, they've fixed it online. Good thing I took a screenshot:

Finally, fellow church music director Frank Pesci points out this MSN story in which the seventh-fastest growing salary in America is revealed to be that paid to "music directors and composers". (We're tied with agricultural inspectors! We're at least as important to the economy as detecting whether that turnip is really organic or not!) And I see by the average that some of you bourgeois pigs out there are making 50 grand a year at this. No kidding! Next time I'm out with other composers, they're buying—and I'm ordering good beer.

January 09, 2008

A quoi ça sert l'amour?

The president of France apparently has a thing for the progeny of composers. If you recall, back in October, President Nicolas Sarkozy announced that he had divorced his second wife, Cécilia Ciganer-Albéniz, a great-granddaughter of the Spanish composer-pianist Isaac Albéniz. Now, a mere three months later, rumors are swirling that Sarkozy is about to marry his new girlfriend, the model-turned-singer Carla Bruni.

Bruni is the stepdaughter of the late Italian composer Alberto Bruni Tedeschi (1915-1996), who divided his time, Ives-like, between composing and running CEAT (Cavi Electrici Affini Torino), the tire and cable company founded by his father. (Bruni Tedeschi sold CEAT to the Italian tire giant Pirelli in the 1970s, but the brand lives on via its Indian subsidiary, founded in 1958.) From 1959 to 1971, he was also sovritendente of the Teatro Regio di Torino (where the current music director is the increasingly in-demand Gianandrea Noseda). Bruni Tedeschi's music is mostly in a romantic-modernist style reminiscent of Dallapiccola; there's a plethora of recordings and videos on his posthumous website. Still, his leading passion seems to have been collecting—art, furniture, houses, all manner of stuff.

Carla Bruni got her start as a model for Guess jeans back in the 80s, and, as every single news article about her never fails to mention, has at one time or another dated Eric Clapton, Donald Trump, Kevin Costner, and, most infamously, Mick Jagger, driving Jagger's wife Jerry Hall to distraction for the better part of a decade. Until recently, she was married to the philosopher Raphaël Enthoven, who she began an affair with while she was still in a relationship with Enthoven's father; the younger Enthoven's wife at the time, Justine Lévy (daughter of the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy), later wrote a thinly-diguised roman-á-clef about the whole scandal. Did you follow that? Then again, Sarkozy met his second wife when, as mayor of Neuilly, he officiated at her wedding to somebody else. They sound like they were made for each other.

But even the normally tolerant French find the quick turnaround a little unseemly—the latest polls show that Sarkozy's approval rating has dropped nearly 20 points since the summer, and 7 points in the last month alone. It should be noted that Sarkozy's disinclination to keep his private life private—the couple took a well-publicized Christmas trip to Egypt—is in stark contrast with his predecessors, who have traditionally been discreet with their amorous activities while in office. The problem is not the affair, in other words, but that, in flaunting it, Sarkozy is coming off as a bit gauche—a danger for someone whose predilection for the luxuries offered by his wealthy friends and supporters have already earned him the derisive title of le Président Bling-Bling.

But this is a music blog, after all, so let's get to the real question: can Carla Bruni sing? Well, she has better pitch than Rex Harrison, at least. Personally, I don't go in for ultra-wispy breathiness (except from Blossom Dearie in one of her sly moods), but more than a few Europeans do, based on the success of her 2004 debut single, "Quelqu'un m'a dit." She gets this sincere compliment: she's the polar opposite of American Idol.

January 07, 2008

In the corners of my mind

The weekend's non-required reading was Daniel Goldmark's Tunes for 'Toons: Music and the Hollywood Cartoon. Goldmark does some breakdown of compositional practice in the Golden Age of Hollywood animation, but the focus is mostly on cultural studies: what the way that music was used in cartoons tells us about how various types of music were viewed and referenced at the time. It's a fun, fun book, although you get the feeling that Goldmark has simplified his analysis somewhat in order not to scare off a non-specialist audience. You're a college professor—go ahead and write that tome! Still, a welcome addition to a library category that remains scandalously small.

Goldmark, inevitably, spends a chapter analyzing the Chuck Jones-directed Bugs Bunny Wagner parody "What's Opera, Doc?". If you're one of the four people who have never seen the cartoon, you can watch it here. (For my money, "Rabbit of Seville" is funnier. But I digress.) "What's Opera, Doc?" has become such a staple that it's taken on a life of it's own, beyond parody—as I was reading, I realized that uses of "Ride of the Valkyries" in TV or advertising over the past couple decades or so are probably referring just as much to the cartoon as to the original opera. In other words, it's taking advantage not of our collective knowledge of Die Walküre, but of our collective knowledge of Elmer Fudd singing "Kill the wabbit."

That's a fairly odd state of affairs, even given the way popular culture appropriates anything it can get its hands on. You can compare another warhorse, the "Ode to Joy" from Beethoven's Symphony no. 9. The "Ode" has made its way through pop culture, probably most famously in the Bruce Willis Die Hard franchise. (A grungy guitar version turns up in the trailer to last year's Live Free or Die Hard.) Yet the piece remains stubbornly fixed in its Ninth-Symphony context.

Over Christmas (hence, you may have missed it), the Slovenian philosopher/iconoclast Slavoj Žižek made a surprise visit to the New York Times, ruminating on the European Union's adoption of the "Ode to Joy" as their anthem, in light of his own idiosyncratic hearing of the original. Jonathan at "Dial 'M'" didn't think much of the article—me, I rather enjoyed it. But regardless of whether you buy Žižek's argument or not, the point is, his intellectual strategy was dead-on. The EU chose the Beethoven for their anthem precisely because they wanted to appropriate the perceived qualities of the original: a paean to freedom and brotherhood. Žižek, looking to poke mischievous holes in the EU's self-image, knew that muddling the original context of the "Ode" would be the best way to undermine the EU's use of it. Goldmark, on the other hand, barely mentions the original context of the Wagner selections in "What's Opera, Doc?"—he correctly points out that the cartoon instead follows a generic operatic narrative for which Wagner's music serves merely as a signal. The music has become so shorn of its original context that even someone who has no knowledge of the Ring responds to it in a semiotically particular way. (Here's another way to think about it: if the late Karlheinz Stockhausen had created Hymnen, his electronic national-anthem kaleidoscope, in the past five years rather than the late 60s, he would have been faced with the decision whether to include the EU anthem or not: a recognizable bit of the "Ode to Joy" would almost certainly be heard as a comment on Beethoven's Ninth rather than the EU, or nationalism in general.)

Why is this? I don't know. It could be that more people have experienced the Beethoven in its original context—performances of the Ninth are certainly more common, and readily accessible, than performances of the Ring. It could be that more people have actually sung the Beethoven, probably in the form of Henry Van Dyke's hymn "Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee"—perhaps that's fixed the "Ode" as a specifically musical experience instead of a more generically "cultural" one. It could be a sign of the success that propagandists had in associating Wagner with the Nazis in World War II—and, in turn, disassociating it from the actual operas. (Goldmark points out that much of the imagery of "What's Opera, Doc?" is foreshadowed in a WWII-era anti-Nazi Bugs Bunny short, "Herr Meets Hare"—although the music in that one was, curiously, Strauss waltzes.) It could be the more stylized (read: more easily parodied) aspects of opera vs. concert music. Or it could, after all, just be one of those quirks of history—I actually gravitate towards this one, since the idea of a piece of music having a biography as wayward and rich as a person appeals to me.

Of course, I haven't yet mentioned the most famous post-Bugs use of Wagner, the helicopter assault in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (the "Ride" begins around the 3:20 mark).

This is an absolutely fascinating use of the music because the movie gets to have it both ways. No doubt Coppola and his screenwriter, John Milius, were fully aware of the plot of Die Walküre, the ingenious portrayal of the helicopter gunships as modernized, mechanized Valkyries—the music both romanticizes combat and wryly points out the absurdity of ancient notions of chivalry in a war where the killing is almost industrialized. But Coppola also gets the benefit of the general, vague familiarity with the piece, giving the scene an almost banal overtone that works in counterpoint with the intense violence.

The most intriguing detail of the use of the music is that it's diagetic, that is, it actually exists within the movie. We hear the "Ride" because the soldiers are hearing it: Col. Kilgore (Robert Duvall) explains its presence, gives the "psyops" order, and we see the reel-to-reel tape begin to play. It's a way to massage the surrealism of the soundtrack, and I think it's very subtly aided by the shared 20th-century music-appreciation-via-cartoon that "What's Opera, Doc?" epitomizes. The film's creators may have familiarized themselves with the mythology of the Ring, but the surfing Army lifer Col. Kilgore? He probably learned it from Bugs Bunny.

Goldmark, inevitably, spends a chapter analyzing the Chuck Jones-directed Bugs Bunny Wagner parody "What's Opera, Doc?". If you're one of the four people who have never seen the cartoon, you can watch it here. (For my money, "Rabbit of Seville" is funnier. But I digress.) "What's Opera, Doc?" has become such a staple that it's taken on a life of it's own, beyond parody—as I was reading, I realized that uses of "Ride of the Valkyries" in TV or advertising over the past couple decades or so are probably referring just as much to the cartoon as to the original opera. In other words, it's taking advantage not of our collective knowledge of Die Walküre, but of our collective knowledge of Elmer Fudd singing "Kill the wabbit."

That's a fairly odd state of affairs, even given the way popular culture appropriates anything it can get its hands on. You can compare another warhorse, the "Ode to Joy" from Beethoven's Symphony no. 9. The "Ode" has made its way through pop culture, probably most famously in the Bruce Willis Die Hard franchise. (A grungy guitar version turns up in the trailer to last year's Live Free or Die Hard.) Yet the piece remains stubbornly fixed in its Ninth-Symphony context.

Over Christmas (hence, you may have missed it), the Slovenian philosopher/iconoclast Slavoj Žižek made a surprise visit to the New York Times, ruminating on the European Union's adoption of the "Ode to Joy" as their anthem, in light of his own idiosyncratic hearing of the original. Jonathan at "Dial 'M'" didn't think much of the article—me, I rather enjoyed it. But regardless of whether you buy Žižek's argument or not, the point is, his intellectual strategy was dead-on. The EU chose the Beethoven for their anthem precisely because they wanted to appropriate the perceived qualities of the original: a paean to freedom and brotherhood. Žižek, looking to poke mischievous holes in the EU's self-image, knew that muddling the original context of the "Ode" would be the best way to undermine the EU's use of it. Goldmark, on the other hand, barely mentions the original context of the Wagner selections in "What's Opera, Doc?"—he correctly points out that the cartoon instead follows a generic operatic narrative for which Wagner's music serves merely as a signal. The music has become so shorn of its original context that even someone who has no knowledge of the Ring responds to it in a semiotically particular way. (Here's another way to think about it: if the late Karlheinz Stockhausen had created Hymnen, his electronic national-anthem kaleidoscope, in the past five years rather than the late 60s, he would have been faced with the decision whether to include the EU anthem or not: a recognizable bit of the "Ode to Joy" would almost certainly be heard as a comment on Beethoven's Ninth rather than the EU, or nationalism in general.)

Why is this? I don't know. It could be that more people have experienced the Beethoven in its original context—performances of the Ninth are certainly more common, and readily accessible, than performances of the Ring. It could be that more people have actually sung the Beethoven, probably in the form of Henry Van Dyke's hymn "Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee"—perhaps that's fixed the "Ode" as a specifically musical experience instead of a more generically "cultural" one. It could be a sign of the success that propagandists had in associating Wagner with the Nazis in World War II—and, in turn, disassociating it from the actual operas. (Goldmark points out that much of the imagery of "What's Opera, Doc?" is foreshadowed in a WWII-era anti-Nazi Bugs Bunny short, "Herr Meets Hare"—although the music in that one was, curiously, Strauss waltzes.) It could be the more stylized (read: more easily parodied) aspects of opera vs. concert music. Or it could, after all, just be one of those quirks of history—I actually gravitate towards this one, since the idea of a piece of music having a biography as wayward and rich as a person appeals to me.

Of course, I haven't yet mentioned the most famous post-Bugs use of Wagner, the helicopter assault in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (the "Ride" begins around the 3:20 mark).

This is an absolutely fascinating use of the music because the movie gets to have it both ways. No doubt Coppola and his screenwriter, John Milius, were fully aware of the plot of Die Walküre, the ingenious portrayal of the helicopter gunships as modernized, mechanized Valkyries—the music both romanticizes combat and wryly points out the absurdity of ancient notions of chivalry in a war where the killing is almost industrialized. But Coppola also gets the benefit of the general, vague familiarity with the piece, giving the scene an almost banal overtone that works in counterpoint with the intense violence.

The most intriguing detail of the use of the music is that it's diagetic, that is, it actually exists within the movie. We hear the "Ride" because the soldiers are hearing it: Col. Kilgore (Robert Duvall) explains its presence, gives the "psyops" order, and we see the reel-to-reel tape begin to play. It's a way to massage the surrealism of the soundtrack, and I think it's very subtly aided by the shared 20th-century music-appreciation-via-cartoon that "What's Opera, Doc?" epitomizes. The film's creators may have familiarized themselves with the mythology of the Ring, but the surfing Army lifer Col. Kilgore? He probably learned it from Bugs Bunny.

January 05, 2008

Everything the traffic will allow

Reviewing the Boston Pops' new CD.

Boston Globe, January 6, 2008.

Boston Globe, January 6, 2008.

Labels:

Globe Articles

January 04, 2008

What a movie

Psst... hey, Hollywood:

Sean Penn as Leonard Bernstein. Just a suggestion.

Sean Penn as Leonard Bernstein. Just a suggestion.

Penn photo by the Associated Press. Bernstein photo by Jack Mitchell.

Update (1/4): Our good friend Mark Meyer works the requisite celluloid magic:

Sean Penn as Leonard Bernstein. Just a suggestion.

Sean Penn as Leonard Bernstein. Just a suggestion.Penn photo by the Associated Press. Bernstein photo by Jack Mitchell.

Update (1/4): Our good friend Mark Meyer works the requisite celluloid magic:

Who is the partisan whose deeds are unsurpassed?

Kim [Il-Sung] described his father as a young man consumed by patriotism who exhorted his schoolmates: "Believe in a Korean God, if you believe in one!" After the family moved to Manchuria, his father went to every service at a local chapel and sometimes led the singing and played the organ, teaching his son to play also. But this, insisted Kim, was just a chance to spread anti-Japanese propaganda.Kim Il-Sung, the authoritarian ruler of North Korea for over forty years, started out as a church organist? Explains an awful lot, actually.

...

By 1947, [Kim] had become the center of a personality cult, modeled on Stalin's, in which he was pictured as wise, strong, compassionate—and energetic enough to involve himself in virtually every significant decision. He was reported to have supervised closely even the composition of the national anthem. Perhaps calling upon his experience as a church organist, he urged the committee involved to insert a refrain between the verses, to "improve the rhythm and harmony of the music [and] add to the solemnity of the song as a whole, and inspire the singer with national pride and self-confidence." According to an official biography, "none of the poets and composers assembled there had thought of this until he pointed it out."—Bradley K. Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly

Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty (pp. 16, 59)

January 02, 2008

Come Fly With Me

The death of Oscar Peterson on Christmas Eve caused a brief spike in what I think to be one of the most fascinating tropes in music reception: the reflexive mistrust of virtuosity. Peterson, was, of course, one of the greatest virtuosos of the past hundred years. A lot of the coverage of his passing, even that in a favorable tone, still cast a qualified eye towards all that technique.

In other words, I never thought that Peterson was letting his technique go on autopilot; rather, he was always putting his technique at the service of the rhythm. A lot of the critical ambivalence towards Peterson may have also had to do with another 20th-century trope, the idea that harmonic innovation is more important than rhythmic innovation. (I sometimes think that, a hundred years from now, the real importance of atonality will not be its supposed emancipation of dissonance, but that its abandonment of specifically harmonic tension and resolution enabled explosive growth in the field of rhythmic possibility.) Peterson's allegiance to blues-based harmonies was simply a result of his creativity being more fully engaged in sculpting the rhythmic flow. Peterson's rhythm is often compared to Count Basie's, that hard, rock-solid swing, but Peterson's technique let him keep that swing in more fluid, moment-to-moment play. It's telling that, when I went from Peterson to Thelonious Monk, it didn't seem all that big a jump to me. To my ear, Monk was using silence and accents the way Peterson used streams of notes and flourishes.

The difference, though, was that the basic building blocks of Monk's vocabulary were the basic building blocks of sound: hard attack, soft attack, loud sound, soft sound, no sound. For Peterson, one of the main components of his vocabulary was his virtuosity, in the same way as a Chopin or a Liszt: technical difficulty, and the overcoming of technical difficulty, as an expressive resource in and of itself. Nowadays, whether out of a need for some sense of "authenticity," or some inability to connect the craft with the art, or maybe even simply the lack of widespread instrumental musical experience as a frame of reference, Monk's style (which, it should be pointed out, was just as much constructed and polished and practiced as Peterson's) is held up as more "emotional", "soulful", "communicative"—insert your own word. I like Monk and Peterson, in large part because I don't regard virtuosity as a sort of second-class musical element. But a lot of people do.

So why this distrust of virtuosity, this assumption that somehow, if your technique is astonishingly good, your emotional connection with the music must necessarily suffer? I think it has to do with the similarity between music and magic. (I've talked about this before; it's one of my favorite pet ideas.) And, by extension, the connection between magic and outright chicanery. Magic is, after all, a benign con; at a certain point, the patter becomes so smooth and faultless that we instinctively start to protect our valuables. With virtuosity, too—it's that omnipresent fear of looking like a rube or a fool. So instead of the natural reaction, which is to just let one's jaw drop all the way to the floor, we try and assert some control over the situation, establish some parameter where we can at least seem to be engaging the experience on equal terms with the performer. And a big part of that is dismissing what the performer does that we can't as impressive but somehow irrelevant to what really matters. (Professional athletes get this a lot. Yeah, but he's still just throwing a ball.)

In Peterson's case, this was exacerbated by the fact that the emotional content of much of his music-making was built around one of the most basic but uncomplicated emotions there is: joy. I don't think it was a case of cynicism resisting that joy, just that it was so obvious that perhaps a critical exploration of it didn't seem necessary, or didn't seem to go beneath the surface. But that joy was powerful stuff, indeed. Every day, Oscar Peterson, a high-school dropout from suburban Toronto, the son of black immigrants, sat behind the piano and did things that nobody else on the planet could do. If you don't think that there's a deeply profound statement about the human condition right there, you're just not paying attention.

Though Peterson has sometimes been criticised as a musician in thrall to his own runaway technique, he remained a great virtuoso of piano jazz, and an equally effective populariser of the music among those who might otherwise not have encountered it.I wasn't going to bother with my own obituary of Peterson, since I figured it would simply be a lot of fanboy gushing: Peterson was the first jazz pianist I ever heard (via record albums appropriated from my dad—thanks, Dad), he pretty quickly became my favorite, and he never really relinquished the crown, although I fully admit I never had the time to keep up with his fearsomely prodigious output of recordings. If I'm going to talk about his virtuosity, though, it might be helpful to briefly analyze just what it was that set Peterson's playing apart. Lots of pianists play fast; some of them play extremely fast. But Peterson played extremely fast and swung very hard, which is kind of a violation of piano physics. It's relatively easy for fast passagework to either float above the beat or get you from a particular beat A to beat B. (This is why I've always thought the phrases in bebop tunes are always beginning and ending on odd parts of the bar—it delineates the outline of the swing without necessarily having to swing itself. It's very cool in an op-art sort of way.) Peterson could judiciously vary the touch, tone, and weight of every one of those many notes so that the swing was embedded within the passagework. It was simultaneously solo and rhythm section. Pianists know how amazing this is; it's the same as practicing a Scarlatti sonata for hours on end, trying to even out the sixteenth notes, then hearing Horowitz do it with such preternatural smoothness that you just throw up your hands. I never met another pianist who didn't regard Peterson with awe. We'd tried it. We knew how hard he had worked to be able to do what he did.—John Fordham in The Guardian

Accolades followed him everywhere, but Peterson always had to fend off some critics who believed his technical prowess outweighed his ability to express emotion on the keyboard.—Jeffrey Jones for Reuters

The critical ambivalence was typified in 1973 by a review of a Peterson performance by John S. Wilson of The Times. Mr. Wilson wrote: “For the last 20 years, Oscar Peterson has been one of the most dazzling exponents of the flying fingers school of piano playing. His performances have tended to be beautifully executed displays of technique but woefully weak on emotional projection.”

The complaints evoked those heard in the 1940s about the great concert violinist Jascha Heifetz, who was occasionally accused of being so technically brilliant that one could not find his or the composer’s heart and soul in the music he played.—Richard Severo in The New York Times

In other words, I never thought that Peterson was letting his technique go on autopilot; rather, he was always putting his technique at the service of the rhythm. A lot of the critical ambivalence towards Peterson may have also had to do with another 20th-century trope, the idea that harmonic innovation is more important than rhythmic innovation. (I sometimes think that, a hundred years from now, the real importance of atonality will not be its supposed emancipation of dissonance, but that its abandonment of specifically harmonic tension and resolution enabled explosive growth in the field of rhythmic possibility.) Peterson's allegiance to blues-based harmonies was simply a result of his creativity being more fully engaged in sculpting the rhythmic flow. Peterson's rhythm is often compared to Count Basie's, that hard, rock-solid swing, but Peterson's technique let him keep that swing in more fluid, moment-to-moment play. It's telling that, when I went from Peterson to Thelonious Monk, it didn't seem all that big a jump to me. To my ear, Monk was using silence and accents the way Peterson used streams of notes and flourishes.

The difference, though, was that the basic building blocks of Monk's vocabulary were the basic building blocks of sound: hard attack, soft attack, loud sound, soft sound, no sound. For Peterson, one of the main components of his vocabulary was his virtuosity, in the same way as a Chopin or a Liszt: technical difficulty, and the overcoming of technical difficulty, as an expressive resource in and of itself. Nowadays, whether out of a need for some sense of "authenticity," or some inability to connect the craft with the art, or maybe even simply the lack of widespread instrumental musical experience as a frame of reference, Monk's style (which, it should be pointed out, was just as much constructed and polished and practiced as Peterson's) is held up as more "emotional", "soulful", "communicative"—insert your own word. I like Monk and Peterson, in large part because I don't regard virtuosity as a sort of second-class musical element. But a lot of people do.

So why this distrust of virtuosity, this assumption that somehow, if your technique is astonishingly good, your emotional connection with the music must necessarily suffer? I think it has to do with the similarity between music and magic. (I've talked about this before; it's one of my favorite pet ideas.) And, by extension, the connection between magic and outright chicanery. Magic is, after all, a benign con; at a certain point, the patter becomes so smooth and faultless that we instinctively start to protect our valuables. With virtuosity, too—it's that omnipresent fear of looking like a rube or a fool. So instead of the natural reaction, which is to just let one's jaw drop all the way to the floor, we try and assert some control over the situation, establish some parameter where we can at least seem to be engaging the experience on equal terms with the performer. And a big part of that is dismissing what the performer does that we can't as impressive but somehow irrelevant to what really matters. (Professional athletes get this a lot. Yeah, but he's still just throwing a ball.)

In Peterson's case, this was exacerbated by the fact that the emotional content of much of his music-making was built around one of the most basic but uncomplicated emotions there is: joy. I don't think it was a case of cynicism resisting that joy, just that it was so obvious that perhaps a critical exploration of it didn't seem necessary, or didn't seem to go beneath the surface. But that joy was powerful stuff, indeed. Every day, Oscar Peterson, a high-school dropout from suburban Toronto, the son of black immigrants, sat behind the piano and did things that nobody else on the planet could do. If you don't think that there's a deeply profound statement about the human condition right there, you're just not paying attention.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)