I finished a piece last night—a short song cycle on a few of Sandburg's "Chicago Poems"—and already this morning my peripatetic brain has moved on to greener pastures. I find this happening to me all the time: as soon as a project is done, the next project immediately moves in and evicts all trace of the previous tenant.

I guess a certain amount of creative restlessness is a good thing, but I wonder if other composers/writers/creative types have this problem. And it is a problem, particularly for a composer. We're supposed to be out there, self-promoting, getting performers interested in our work, etc., etc., but as soon as the work's on paper, it takes a fair amount of effort for me to remain interested in it. How am I supposed to get other people excited about a piece that I hardly think about? (Just last night, this blog's muse and better half happened to mention a string quartet I wrote seven or eight years ago. Nice piece, I think—she reminded me that I should send it around to a few groups. Which I might have done, had a single conscious awareness of its existence crossed my mind since the last time I chanced upon a copy.) It's a contradiction: the composer side of me has to be dissatisfied enough to always be pushing ahead, while the career side of me needs to, in effect, wallow in alleged past glories. (I err on the former side, which the state of my career can attest to.)

In fact, as I was proofreading this latest piece, I realized that, in looking at the first song I wrote, I've already forgotten where a fair share of those notes came from, compositionally speaking. This is partially due to the habit I have of using fairly schematic methods to jump-start a piece, and then, once I have a critical mass of sounds I like, letting intuition take over. But one of my greatest fears (I suppose it's not all that objectively great; I'm pretty foolhardy) is that someone will ask me to talk about a piece of mine from a theoretical/craft point of view, and I'll have nothing to say. (And the few times I've set a piece aside and then come back to it a few months later? An awful lot of rope-pulling to get that mower started again.) Maybe I should do like that guy in "Memento"—I can end up with matrices and key relationships and generating motives tattooed all over myself.

(By the way, if all you know of Carl Sandburg are the same four poems that are anthologized everywhere, you're missing out on one of the greats. Quality work avoidance begins here.)

August 31, 2006

August 30, 2006

Booty Call

Now this looks like serious fun. "PLAY.orchestra" is an outreach project by the Philharmonia Orchestra over in the UK. They've set up an outdoor courtyard with 58 boxes like this one:

Each box represents an instrument, and the boxes are laid out like an orchestra. Sit on the box, and it starts playing that instrument's individual part in a piece. Bring a mob, and you can hear the whole band. The boxes loop two new pieces a week: something from the standard rep, and a commissioned piece from a young composer. (This week's premiere is Flux by Fung Lam.)

I don't know what kind of response it's getting, but the orchestra is certainly giving it a go. There's weekly "guided tours" of the virtual orchestra, to which you can add your own real instruments—all the commissioned pieces have extra parts suitable for amateurs. And there's technical types there to show you how to record the resultant sounds as a cellphone ringtone.

This is so brilliantly goofy that I'm currently researching what kind of burnt offerings I need to make to get it across the Atlantic. Can you imagine setting loose a gaggle of kids on these things? You could fill up Boston Common with them and do Mahler 8. You could stuff the technology into seat cushions and make everyone at Fenway park it for the national anthem. This is perfect for people who are supposedly too put off, intimidated, whatever, to go into a concert hall. It's out in the open and effortless—all you need is your butt. I wonder how "Song to the Moon" would sound.

Each box represents an instrument, and the boxes are laid out like an orchestra. Sit on the box, and it starts playing that instrument's individual part in a piece. Bring a mob, and you can hear the whole band. The boxes loop two new pieces a week: something from the standard rep, and a commissioned piece from a young composer. (This week's premiere is Flux by Fung Lam.)

I don't know what kind of response it's getting, but the orchestra is certainly giving it a go. There's weekly "guided tours" of the virtual orchestra, to which you can add your own real instruments—all the commissioned pieces have extra parts suitable for amateurs. And there's technical types there to show you how to record the resultant sounds as a cellphone ringtone.

This is so brilliantly goofy that I'm currently researching what kind of burnt offerings I need to make to get it across the Atlantic. Can you imagine setting loose a gaggle of kids on these things? You could fill up Boston Common with them and do Mahler 8. You could stuff the technology into seat cushions and make everyone at Fenway park it for the national anthem. This is perfect for people who are supposedly too put off, intimidated, whatever, to go into a concert hall. It's out in the open and effortless—all you need is your butt. I wonder how "Song to the Moon" would sound.

August 29, 2006

Product, Pricing, Promotion, Pompousness

The New York Times reports today that the Metropolitan Opera, realizing that it's almost the 1980's, for gosh sakes, has unveiled an advertising campaign. Images promoting their upcoming production of "Madama Butterfly" are gracing subway stations, buses, and the like as we speak.

It's a tectonic shift for the Met, who have historically disdained such self-promotion, correctly reasoning that their subscriber base hasn't left the house since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Peter Gelb wants to change all that, though, taking square marketing aim at, in the Times' words, "younger people who may find opera remote and intimidating." (Actually, the ads are still a little too square. Can't they borrow a cup of shameless sensationalism from the Post? HARA-KIRI FOR SORDID SAILOR'S GORGEOUS GEISHA. You know, something like that.)

I suppose it's good that the Met is finally emerging, blinking and squinting, from their gilded cage. (Although I love the fact that even their advertising campaign has a wealthy patron.) But that's just me.

Fallacy #1: "Highbrow" can't be "popular." Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Fallacy #2: "The young are not necessarily the hip." You're the one segregating by hipness, Leon—the Met is going after young people period. A good move, too: the nerd demographic has both greater numbers and earning potential.

Fallacy #3: (Ignoring Fallacy #2 for a minute.) "The hip" is not going to sell out the Met? The Met has 4,000 seats. Assume they actually did put on something "hip." You don't think there's 4,000 hip people in New York? There's probably at least 4,000 opera singers in New York. (Heck, for Turandot, I think the Met crams 4,000 people on the stage.) I would question the fundamental issue of how hip the Met can make itself, but the demographics have got to be working against Wieseltier here.

Gawker says it best: "Yeah, we want to drop three hundred bucks to sit next to that guy." Worry not, friend—if Leon goes to the Met at all, he sits up in the boxes and leaves in a snit after the first act because he can't stop orating and everyone keeps shushing him. Take my advice: get a walk-up ticket and sneak in a flask of cheap port and some Raisinets. And if you end up next to me, I promise that, if I do use the phrase "pharaonically large", I'll at least try to make it sound like a double entendre.

It's a tectonic shift for the Met, who have historically disdained such self-promotion, correctly reasoning that their subscriber base hasn't left the house since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Peter Gelb wants to change all that, though, taking square marketing aim at, in the Times' words, "younger people who may find opera remote and intimidating." (Actually, the ads are still a little too square. Can't they borrow a cup of shameless sensationalism from the Post? HARA-KIRI FOR SORDID SAILOR'S GORGEOUS GEISHA. You know, something like that.)

I suppose it's good that the Met is finally emerging, blinking and squinting, from their gilded cage. (Although I love the fact that even their advertising campaign has a wealthy patron.) But that's just me.

“Opera will never again be a popular taste, and coaxing masses of young people into highbrow pleasures isn’t easy. The young are not necessarily the hip, and the hip is not necessarily what will sell out a pharaonically large venue.”The twenty-five-cent words of Leon Wieseltier, pontificating at the end of the Times article (hey, for once they buried the trash, and not the lede). Putting aside from his annoying use of hip as a noun (he's probably one of those people who refers to "the gay"), this sentence is still a mess.

Gawker says it best: "Yeah, we want to drop three hundred bucks to sit next to that guy." Worry not, friend—if Leon goes to the Met at all, he sits up in the boxes and leaves in a snit after the first act because he can't stop orating and everyone keeps shushing him. Take my advice: get a walk-up ticket and sneak in a flask of cheap port and some Raisinets. And if you end up next to me, I promise that, if I do use the phrase "pharaonically large", I'll at least try to make it sound like a double entendre.

August 28, 2006

August 25, 2006

What fools these mortals be

I'm playing a wedding this weekend. It's the first wedding gig I've had in a couple years, and I realized this morning that I'd lost my copy of the Bridal Chorus from Wagner's Lohengrin. So I figured I'd pull it off the web; it's in the public domain, it's out there somewhere.

I found it in about a minute—but the search also turned up a number of church wedding music guidelines that expressly forbid it. Why?

1. "Part of the problem is that [its] use is a Hollywood invention." No, actually, the first use of the "Bridal Chorus" in an actual ceremony was in 1858, at the wedding of Queen Victoria's daughter.

2. "[In the opera,] we watch as suspicion triumphs over love, and the marriage celebrated ends before it begins." Well, they do at least get through the vows. And suspicion does dissolve the couple, but only because the husband won't tell his wife his freakin' name... that seems a little extreme even for James Dobson. (And how many weddings have been similarly graced with "One Hand, One Heart"? Anybody remember how that one ends?)

3. "This instrumental piece originated from theatrical, operatic repertoire." Flip through a hymnal and ask yourself if the church really wants to start going down that road.

4. "The impression created by this piece is that the focus is on the bride alone." Guess what, guys: when she's coming up the aisle—it is. Even if you play "The Lady is a Tramp." (Or even "Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus.")

What really got me was not the reasons they chose, which seem to me to be on the same level as early Puritan debates over infant baptism (try those for your next bout of insomnia), but that they conspicuously ignore the one good reason for keeping Wagner out of the church: namely, that he was an anti-Semitic jerk. Then again, this is a Unitarian wedding I'm playing—maybe surrounding the tune with all those everybody's-welcome-here vibes will stick in Richard's purgatorial craw. Serves him right.

And the title of this post? Well, I also get to play the "Wedding March" from Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream music. Sure, it's the warhorse to end all warhorses, but I love it, and I'll program it at the drop of a hat. (The man starts on a ii-half-diminished of iii, and somehow gets back to tonic within three bars. It's like music theory porn.) Turns out that this one's no good, either—that "Hollywood" thing again (nope; used in ceremonies as early as 1847), and then this:

I found it in about a minute—but the search also turned up a number of church wedding music guidelines that expressly forbid it. Why?

1. "Part of the problem is that [its] use is a Hollywood invention." No, actually, the first use of the "Bridal Chorus" in an actual ceremony was in 1858, at the wedding of Queen Victoria's daughter.

2. "[In the opera,] we watch as suspicion triumphs over love, and the marriage celebrated ends before it begins." Well, they do at least get through the vows. And suspicion does dissolve the couple, but only because the husband won't tell his wife his freakin' name... that seems a little extreme even for James Dobson. (And how many weddings have been similarly graced with "One Hand, One Heart"? Anybody remember how that one ends?)

3. "This instrumental piece originated from theatrical, operatic repertoire." Flip through a hymnal and ask yourself if the church really wants to start going down that road.

4. "The impression created by this piece is that the focus is on the bride alone." Guess what, guys: when she's coming up the aisle—it is. Even if you play "The Lady is a Tramp." (Or even "Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus.")

What really got me was not the reasons they chose, which seem to me to be on the same level as early Puritan debates over infant baptism (try those for your next bout of insomnia), but that they conspicuously ignore the one good reason for keeping Wagner out of the church: namely, that he was an anti-Semitic jerk. Then again, this is a Unitarian wedding I'm playing—maybe surrounding the tune with all those everybody's-welcome-here vibes will stick in Richard's purgatorial craw. Serves him right.

And the title of this post? Well, I also get to play the "Wedding March" from Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream music. Sure, it's the warhorse to end all warhorses, but I love it, and I'll program it at the drop of a hat. (The man starts on a ii-half-diminished of iii, and somehow gets back to tonic within three bars. It's like music theory porn.) Turns out that this one's no good, either—that "Hollywood" thing again (nope; used in ceremonies as early as 1847), and then this:

The Mendelssohn march was written for the marriage of a young woman to a satyr—half man and half horse!No, it wasn't, you dimwit, it was written for the triple marriage that's celebrated in Act V. Does anybody even know how to crack open a book anymore? Yeesh.

August 24, 2006

Who's Looking Out for You?

A couple things:

Mea culpa: Mere hours after I asserted that only classical music fans make a fuss when their radio station changes format, soul and gospel fans are raising a fuss over the sale of WILD-FM here in Boston. With good reason: Entercom Communications plans to use WILD's frequency (heretofore a stream of soul, neo-soul, and classic R&B) to simulcast WAAF, a cookie-cutter classic-rock affair. (Again: they're buying the frequency so thay can broadcast the exact same thing in two places on the dial.) So radio listeners in the predominantly African-American neighborhoods of Dorchester and Roxbury (as well as suburban soul fans like yours truly) are being screwed in favor of the presumably more advertiser-friendly South Shore frat boy demographic. The only other station that could be euphemistically classified as "urban" in Boston is "Jam'n" 94.5, which limits its playlists to whatever passes for hip-hop these days. (Yeah, I'm even a rap snob. What did you expect?)

In other news, the Music Publishers' Association and the National Music Publishers' Association (yeah, they're two different organizations; so much for the efficiency of free markets) are going after Internet sites that post guitar tabulatures—amateur transcriptions of the guitar parts for pop and rock songs. To put it another way: music publishers apparently aren't making enough money, so they're taking legal action against their own customer base. That'll teach the little ingrates. (And do check out the photo of the head of the Music Pulishers' Association. That has got to be the most Freudian, over-compensatory SUV of a tuba I've ever seen. You think this guy reads Forbes?)

About the only mildly impressive thing I can do on a guitar is play "Day Tripper." I didn't buy the music; I didn't even buy the record. I did essentially what a guitar tab site does: I learned it from another guitarist. Is that really illegal? Am I to live in fear of the giant tuba?

What do these stories have in common? To my thinking, it's two instances of government organizations—here, the Federal Communications Commission and the United States Congress—completely screwing the pooch as custodians of culture. The FCC could theoretically have blocked the WILD sale as not being in the public interest, but since 1981, they've been content to let market forces determine the public interest, and only get up from in front of the tube long enough to pull an Olin Blitch every now and again. Congress could have theoretically ignored gazillions of dollars' worth of lobbying and not passed the DMCA, or at least could risk ticking off some corporate types by clarifying "fair use" guidelines in light of the Internet, but... well, they just aren't going to do that, now are they?

So who's watching out for the public cultural interest at the federal level? Nobody. (Even the NEA seems more content to promote that noted American playwright William Shakespeare and spend money to translate the literature of other nations, presumably so future generations of Americans won't have to suffer the indignity of learning a foreign language.) What this country needs is a cabinet-level Secretary of Culture, with dominion over not just the arts and humanities endowments, but the FCC, the Copyright Office, and, for good measure, the Marine Band (and you thought they were just a harmonica). Send me to Congress, and I promise you... oh, wait, that's right, I'm unelectable—I used to carry a copy of the Communist Manifesto around as a teenager. Anybody else want to handle this one?

Mea culpa: Mere hours after I asserted that only classical music fans make a fuss when their radio station changes format, soul and gospel fans are raising a fuss over the sale of WILD-FM here in Boston. With good reason: Entercom Communications plans to use WILD's frequency (heretofore a stream of soul, neo-soul, and classic R&B) to simulcast WAAF, a cookie-cutter classic-rock affair. (Again: they're buying the frequency so thay can broadcast the exact same thing in two places on the dial.) So radio listeners in the predominantly African-American neighborhoods of Dorchester and Roxbury (as well as suburban soul fans like yours truly) are being screwed in favor of the presumably more advertiser-friendly South Shore frat boy demographic. The only other station that could be euphemistically classified as "urban" in Boston is "Jam'n" 94.5, which limits its playlists to whatever passes for hip-hop these days. (Yeah, I'm even a rap snob. What did you expect?)

In other news, the Music Publishers' Association and the National Music Publishers' Association (yeah, they're two different organizations; so much for the efficiency of free markets) are going after Internet sites that post guitar tabulatures—amateur transcriptions of the guitar parts for pop and rock songs. To put it another way: music publishers apparently aren't making enough money, so they're taking legal action against their own customer base. That'll teach the little ingrates. (And do check out the photo of the head of the Music Pulishers' Association. That has got to be the most Freudian, over-compensatory SUV of a tuba I've ever seen. You think this guy reads Forbes?)

About the only mildly impressive thing I can do on a guitar is play "Day Tripper." I didn't buy the music; I didn't even buy the record. I did essentially what a guitar tab site does: I learned it from another guitarist. Is that really illegal? Am I to live in fear of the giant tuba?

What do these stories have in common? To my thinking, it's two instances of government organizations—here, the Federal Communications Commission and the United States Congress—completely screwing the pooch as custodians of culture. The FCC could theoretically have blocked the WILD sale as not being in the public interest, but since 1981, they've been content to let market forces determine the public interest, and only get up from in front of the tube long enough to pull an Olin Blitch every now and again. Congress could have theoretically ignored gazillions of dollars' worth of lobbying and not passed the DMCA, or at least could risk ticking off some corporate types by clarifying "fair use" guidelines in light of the Internet, but... well, they just aren't going to do that, now are they?

So who's watching out for the public cultural interest at the federal level? Nobody. (Even the NEA seems more content to promote that noted American playwright William Shakespeare and spend money to translate the literature of other nations, presumably so future generations of Americans won't have to suffer the indignity of learning a foreign language.) What this country needs is a cabinet-level Secretary of Culture, with dominion over not just the arts and humanities endowments, but the FCC, the Copyright Office, and, for good measure, the Marine Band (and you thought they were just a harmonica). Send me to Congress, and I promise you... oh, wait, that's right, I'm unelectable—I used to carry a copy of the Communist Manifesto around as a teenager. Anybody else want to handle this one?

August 23, 2006

Alcindoro: La convenienza...il grado...la virtù...

Every now and again, I feel a faint regret that I decided on a career in music rather that corporate finance or something like that. I'm a smart guy, I think. I could have made a lot of money. Money is nice.

How do I break out of this funk? Easy; I pick up a copy of Forbes.

In their latest issue, America's favorite Fabergé-egg-hot-air-balloon-and-flat-tax-supporting philanthropy reminds us all that, by gum, nobody's happy when the pants-wearing in the house is on the distaff side. (Article via Boing Boing.) Yes, "if some social scientists are to be believed" (not just one of them, buddy—some of them! So pay attention!) having a wife with a successful career means you're more likely to end up a childless, cuckolded divorcé living in your own filth.

Or not. Let's take a quick gander at a couple of these articles. This is the one that says men get depressed when their better halves are bringing home more bacon. From the abstract:

What does this have to do with music? Well, gosh—having a spouse who makes more than you? Isn't that every composer's dream? I can't think of a single professional musician in this situation who isn't tickled pink that his wife makes more than he does. Could it be that perhaps we're more secure in our manhood? Just askin'.

Virgil Thomson nailed this way back in 1939:

(As long as we're referencing academics, you should consult the estimable Tyler Cowen of George Mason University, who, among other arts-related economic things, has done a fair amount of work on composers and inherited/married wealth. But that's a future post.)

How do I break out of this funk? Easy; I pick up a copy of Forbes.

In their latest issue, America's favorite Fabergé-egg-hot-air-balloon-and-flat-tax-supporting philanthropy reminds us all that, by gum, nobody's happy when the pants-wearing in the house is on the distaff side. (Article via Boing Boing.) Yes, "if some social scientists are to be believed" (not just one of them, buddy—some of them! So pay attention!) having a wife with a successful career means you're more likely to end up a childless, cuckolded divorcé living in your own filth.

Or not. Let's take a quick gander at a couple of these articles. This is the one that says men get depressed when their better halves are bringing home more bacon. From the abstract:

Increases in married women's absolute income generally have nonsignificant effects for married men. However, married men's well-being is significantly lower when married women's proportional contributions to the total family income are increased. The likelihood of divorce is not significantly affected by increases in married women's income. Nevertheless, increases in married women's income may indirectly lower the risk of divorce by increasing women's marital happiness. [emphasis added]So low-income husbands (I do love the stock photo of the schlub they have to accompany the article) may be feeling low, but those marriages are better than ever? Not so fast, says our distinguished magazine: this study, again, is the one that supposedly says no, those upwardly mobile hussies are more likely to call that lawyer. From the abstract:

First, the authors predict change in wives’ employment between the two waves using marital happiness and other Time 1 characteristics. The results show that shifting into full-time employment is more likely for unhappily married than for happily married wives. Second, they examine how changes in wives’ employment between Times 1 and 2 influence marital stability and changes in marital happiness. The authors find that contrary to frequently invoked social and economic theories, wives’ full-time employment is associated with greater marital stability. [emphasis added]Say howdy? Either Forbes is misrepresenting the second article, or that last word is a typo. And if they really did mean to write "instability," wouldn't that be the result of a methodological flaw? It seems from the abstract that they're drawing their conclusions from the pool of women who were stay-at-home wives, but later moved into full-time careers. That's right, the ones whose marriages were more unstable to begin with.

What does this have to do with music? Well, gosh—having a spouse who makes more than you? Isn't that every composer's dream? I can't think of a single professional musician in this situation who isn't tickled pink that his wife makes more than he does. Could it be that perhaps we're more secure in our manhood? Just askin'.

Virgil Thomson nailed this way back in 1939:

A surprisingly large number of composers are men of private fortune. Some of these have it from papa, but the number of those who have married their money is not small. The composer, in fact, is rather in demand as a husband. Boston and New England generally are noted for the high position there allotted to musicians in the social hierarchy and for the number of gifted composers who have in consequence married into flowery beds of ease. I don't know why so many composers marry well, but they do. It is a fact.And hey, with proper and extensive training, we might even do some of the housework.(from the wonderfully titled "How Composers Eat, or Who Does What to Whom and Who gets Paid")

(As long as we're referencing academics, you should consult the estimable Tyler Cowen of George Mason University, who, among other arts-related economic things, has done a fair amount of work on composers and inherited/married wealth. But that's a future post.)

August 22, 2006

Mi, a name I call myself

An interesting story via the BBC's "Newshour" this morning: some Britons are concerned that immigrant British Muslims are increasingly self-segregating with regards to their media consumption, eschewing the mainstream UK television channels in favor of satellite programming from Pakistan, India, and the Middle East. The fear is that, in doing so, they're "not becoming attuned to British ideas" and are thus more susceptible to radicalization.

I think that analysis is both simplistic and overblown (with an important caveat; see below)—I've always considered mass media to be resultant phenomenon, not a causal one—but it got me thinking: what would a similar self-censorship in favor of classical music do to somebody's worldview? My sense is that classical music fans tend to forsake other styles to a greater extent than other entertainment consumers; I mean, nobody raises much of a fuss when a top 40 radio station changes its format, but tamper with a classical station, and fans organize like communists (with a distressingly similar success rate).

Like most practicing musicians, I'm demographically odd in that I'll listen to just about any style. But let's say, for the sake of argument, that I limited my recorded media menu to the glories of German Romanticism—Schumann, Brahms, Wagner, Strauss, Mahler, etc. What would that aesthetic nutrition information panel look like?

Using aphoristic rhetoric to approach the sublime (Schumann) Projecting individual emotional crises onto the physical environment (Schumann, Brahms, and Mahler) Using strict constraints to intensify emotional experience (Brahms) Putting the exceptional individual beyond the strictures of conventional society (Strauss and Mahler) Equating the aesthetic validity of order and chaos (Schumann and Mahler) Equating the respective emotional catharses of love and death (all of them, to varying degrees) World domination (Wagner)

Now there's a profile that'll land you on the no-fly list. But of course it doesn't work that way—which is another reason why trying to draw sociological conclusions from entertainment predilictions is a tricky business. Even the most "passive" viewer/listener brings a host of individual assumptions and emotional experiences to the process of seeing and/or hearing, making all but the most innocuous generalizations risky. From another angle: sure, some of those British Muslims pulling Al Jazeera off the satellite dish might be ripe for radicalization, but that's not going to change just because you convince them to watch "EastEnders" instead.

Hey, what about that caveat? Well, one of the consequences of the unstoppable advance of technology has been the fragmentation of mass media. As such, I think the power of television, radio, the movies, you name it, to be some sort of societal common ground has been diminished. What still alleviates that is our everyday interactions with the outside world and other people—but, given the proliferation of cell phones, instant messaging, and always-on internet connections, it's not hard to imagine a society where every interaction is mediated electronically. And if that happens... that loner down the block who always blasts "Ride of the Valkyries"? I'm keepin' my eye on him.

I think that analysis is both simplistic and overblown (with an important caveat; see below)—I've always considered mass media to be resultant phenomenon, not a causal one—but it got me thinking: what would a similar self-censorship in favor of classical music do to somebody's worldview? My sense is that classical music fans tend to forsake other styles to a greater extent than other entertainment consumers; I mean, nobody raises much of a fuss when a top 40 radio station changes its format, but tamper with a classical station, and fans organize like communists (with a distressingly similar success rate).

Like most practicing musicians, I'm demographically odd in that I'll listen to just about any style. But let's say, for the sake of argument, that I limited my recorded media menu to the glories of German Romanticism—Schumann, Brahms, Wagner, Strauss, Mahler, etc. What would that aesthetic nutrition information panel look like?

Now there's a profile that'll land you on the no-fly list. But of course it doesn't work that way—which is another reason why trying to draw sociological conclusions from entertainment predilictions is a tricky business. Even the most "passive" viewer/listener brings a host of individual assumptions and emotional experiences to the process of seeing and/or hearing, making all but the most innocuous generalizations risky. From another angle: sure, some of those British Muslims pulling Al Jazeera off the satellite dish might be ripe for radicalization, but that's not going to change just because you convince them to watch "EastEnders" instead.

Hey, what about that caveat? Well, one of the consequences of the unstoppable advance of technology has been the fragmentation of mass media. As such, I think the power of television, radio, the movies, you name it, to be some sort of societal common ground has been diminished. What still alleviates that is our everyday interactions with the outside world and other people—but, given the proliferation of cell phones, instant messaging, and always-on internet connections, it's not hard to imagine a society where every interaction is mediated electronically. And if that happens... that loner down the block who always blasts "Ride of the Valkyries"? I'm keepin' my eye on him.

August 21, 2006

Of Thee I Sing, Baby

Driftwood: Well, I uh, I want to sign him up for the New York Opera Company. Do you know America is waiting to hear him sing?Alex Ross has a column in the latest New Yorker that makes passing reference to the quixotic quest for "The Great American Opera." (This entire concept amuses me no end. Do you think music panjandrums in, say, France waste valuable time seeking out "The Great French Opera"? Germany? Well, maybe in Germany.)

Fiorello: Well, he can sing loud, but he can't sing that loud.

Driftwood: Well, I think I can get America to meet him half-way.—The Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera

There isn't a great American opera, of course, and there probably never will be. Blame it all on the venerable idealists who first booted the natives out of my adopted state of Massachusetts. There's a Puritanical streak in the history of American opera. And any of the fundamental concerns of the operatic stage (presented here in alphabetical order) would be a Puritan's nightmare:

(For example: I don't know exactly what my ten favorite operas would be, but three definites: Don Carlos, a conflict of power; Carmen, a conflict of sex; and Turandot, a conflict between people who can't tell the difference. Murders in all three, for those keeping score at home.)

Why should this be? Great swaths of American culture are gleefully vulgar. That is: great swaths of commercial culture. Mind you, all of this flamboyant salaciousness would be fine if opera actually turned a hefty profit, but it doesn't, so it instead falls under the category of tasteful things that are supposedly good for you, in other words, bluestocking fodder.

I bring it up because I think the whole idea of a "Great American Opera" undermines the viability of opera in America, which is a rather different thing. On the face of it, opera seems inherently well-suited to the American media landscape: bigger than life, melodramatic as hell, packed to the gills with spectacle. Trying to take that and make it an Important Artistic Statement On The American Condition is just overloading it with baggage. Can't we just let opera be grand and ruthlessly entertaining?

This may sound like an endorsement of the popular-musicalization of classical music. I admit that opera is the most populist meat in the classical music stew, but that doesn't mean it's pop music. Indeed, I think this obsession with artistic meaningfulness in opera has let pop music move in and take over the cultural role of expressing those emotions that are at the core of opera. I don't think the problem with American opera is that it's not presented as pop music, it's that it's not presented as what it actually is: the familiar territory of pop music exponentially raised to a power that pop music can only dream of.

(Incidentally, if I had to pick a "Great American Opera" [at gunpoint, say] my vote would be Nixon in China—but I think most Americans' reaction to that piece must be a kind of nervous recognition, like the way you wince when you hear a recording of your own voice.)

August 17, 2006

Critic's Corner

In which Moe, our critic-at-large, reviews what's on Matthew's record player.

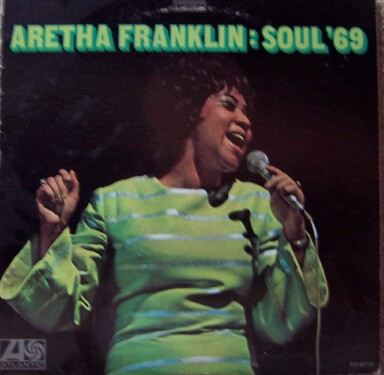

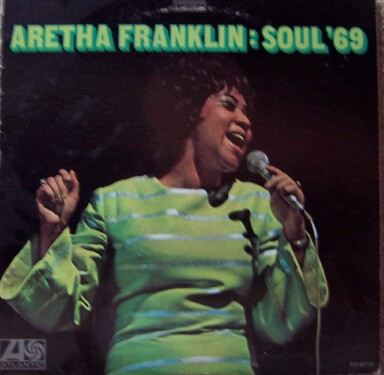

Aretha Franklin: Soul '69

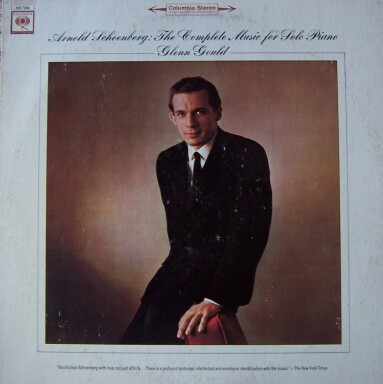

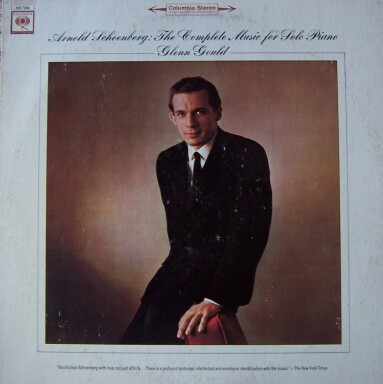

Glenn Gould: Arnold Schoenberg: The Complete Music for Solo Piano

Aretha Franklin: Soul '69

Glenn Gould: Arnold Schoenberg: The Complete Music for Solo Piano

August 16, 2006

Dichter(kein)liebe

In case you didn't know, our local paper here, the Globe, has started running blogs on its entertainment site. (I suppose it's good that they're trying, but if they have money for this sort of thing, I wish they'd spend it on some actual column inches for classical music once in a while, considering how much of it goes on in their alleged metropolitan area. But I digress.)

Anyways, Geoff Edgers has been posting an episodic interview with Ted Libbey, who's just written a tome called The NPR Listener's Encyclopedia of Classical Music. (Apparently NPR plays other types of music than the annoying fake-world-music baby-boomer-guilt-assuaging acoustic trash it uses for bumpers on "Morning Edition." But I digress.)

Anyways, Part 3 of this interview is up, and there's a bit in it that really made me narrow my eyes. Asked what composers he's personally sick of, Libbey says:

Schumann can be a tough nut to crack for performers (it was for me, anyway, but once I got through the shell, yum), but it's significant that singers, who deal with words on a daily basis, love him almost without reservation. So I'm a little suspicious of any writer who doesn't like Schumann, just as I'd be a little suspicious of any painter who couldn't appreciate Debussy, or any pastry chef who didn't care for Strauss, or any mad megalomanaical supervillian without a jukebox full of Wagner.

Anyways, Geoff Edgers has been posting an episodic interview with Ted Libbey, who's just written a tome called The NPR Listener's Encyclopedia of Classical Music. (Apparently NPR plays other types of music than the annoying fake-world-music baby-boomer-guilt-assuaging acoustic trash it uses for bumpers on "Morning Edition." But I digress.)

Anyways, Part 3 of this interview is up, and there's a bit in it that really made me narrow my eyes. Asked what composers he's personally sick of, Libbey says:

Of the canonic "great" composers, Robert Schumann is surely the most overrated. That doesn't mean I'm sick of him...yet.Everybody's got their own tastes, of course, but when a writer on classical music disses Schumann, the most logophilic composer out there, my eyebrow goes up. Schumann not only is an unparalleled master of text-setting, but is one of the only composers to successfully create instrumental works with convincing literary structures—musical short stories and novels that can favorably compare with their word-based counterparts. (Check out the Davidsbündlertänze, an uncanny musicalization of a set of linked descriptive vignettes... and I, at least, am convinced that the Eichendorff-Liederkreis is an embedded meta-narrative in the style of Schumann's favorite novelist, Jean Paul.)

Schumann can be a tough nut to crack for performers (it was for me, anyway, but once I got through the shell, yum), but it's significant that singers, who deal with words on a daily basis, love him almost without reservation. So I'm a little suspicious of any writer who doesn't like Schumann, just as I'd be a little suspicious of any painter who couldn't appreciate Debussy, or any pastry chef who didn't care for Strauss, or any mad megalomanaical supervillian without a jukebox full of Wagner.

August 15, 2006

Great tastes that taste great together

Over at the Globe this morning, Richard Dyer seems to be in an unusually dialectical mood in reviewing a couple of last week's Tanglewood concerts. Historically informed performance vs. unrelieved Romanticism, celebrity vs. musicality, big picture guy vs. micromanager—it's all here, a mouth-watering Hegelian smorgasbord.

And then (referring to said micromanager) Dyer tosses in one last either-or:

Yeah, those things never go together.

And then (referring to said micromanager) Dyer tosses in one last either-or:

He is a truly formidable musician, but an unsmiling one, and there is no room for playfulness or charm in an approach built on precision and power.

Yeah, those things never go together.

August 14, 2006

Follow the money

Now and again, whenever I feel like my blood pressure's not high enough, it's fun to go read some of the blogs over at ArtsJournal. I haven't been doing this on a regular basis, though, so it's only now that I've caught up with Greg Sandow's latest evangelizing for making classical music more like popular music. (There's plenty more where this came from, all well-written and worth perusing.)

The germ of Sandow's argument is that the future health of classical music depends on its maintaining a presence in popular consciousness. He thinks the best way to do this is to package and market it like popular music, encourage more crossover endeavors, and abandon the mindset that classical music is deeper and more artistically meaningful than popular music. I think he's wrong.

Simply put, if you put classical music in competition with popular music on popular music's turf, it loses every time. Popular music has become the prevalent musical culture of our time because there's a lot of money to be made; nobody will ever get (comparatively) rich doing classical music. It's become a commonplace argument that the "decline" of classical music in the second half of the 20th century happened because classical artists abandoned their audience via (take your pick) stuffy formality, over-intellectualization, non-communicative serial music, etc., etc. My own sense is that, outside of the popular media, there's just as much classical music going on today as there was fifty years ago. Classical music isn't on the wane, it's just that popular culture has waxed to an unprecedented degree. And the reasons for that are economic.

Here's my alternate narrative: popular music didn't really become the cash cow it is now until the 1950's—suddenly, post-WWII, teenagers had a lot of disposable income for the first time. They were spending it on popular music (as teenagers have always done), but now, the amount of money they were spending was large enough to attract the attention of individuals and companies who had no inherent interest in the artistic value of the music. They got into the business to make a buck, pure and simple, and that became the driving force in the industry.

In other words, up until the war, all types of music were on a relatively level playing field, financially speaking; there was money to be made, but a) not in a sufficiently unbalanced way to drive entrepreneurs into one type of music over another, and b) not in sufficient amounts to attract non-music-loving capitalists. But once the money became serious, popular music won out. The overhead is less (fewer players means fewer people to pay, as well as cheaper recording costs), the marketing is easier (3-minute blocks of music are an easier sell to advertising-based media than 20-minute blocks), and the possibility for economic exploitation is greater (a far greater emphasis on young, "entry-level" performers translates into a greater corporate share of the profits).

There's also the fact that popular music has lyrics, which means that it's far easier to write and talk about than instrumental classical music. Even today, the vast majority of rock and pop critics can't write about the music in a particularly inspiring way, but they don't have to—they just analyze the words. (I wouldn't mind this if all lyrics were on a Dylan-esque level, but let's face it, not even close.)

Sandow keeps saying that he doesn't want classical music to "dumb down," but all the virtues of classical music—subtlety, intricacy, intellectual engagement, and a grandeur that takes longer than three minutes to build and realize—are at odds with the lowest-common-denominator aesthetic that's the holy grail of popular marketing. Sure, there's popular-style music out there that has a lot of similar virtues, but, like classical music, it's a niche market. And, taken collectively, I think classical music's current niche market is probably larger.

I don't underestimate the need for classical music organizations to market to younger audiences. (Let's just say that the collective accumulated wisdom of a Friday-afternoon Boston Symphony audience is no doubt considerable.) And certainly younger demographics are more media-savvy consumers than classical marketers are used to. But that brings with it a need for the classical world to be that much more honest about what they're offering; if you try and market classical music like popular music, that younger demographic is going to see right through it. At the same time, there's the danger that, in pursuit of a pop-music-sized audience, classical organizations will cross the line between popular marketing and popular aesthetics. The problem with using the marketing trappings of popular culture is that it brings with it the tendency to measure success in the same way: quantity and profitability vs. quality and meaningfulness. Popular culture is beholden to the free market, and the free market is great for determining price, but it's lousy at determining value.

The germ of Sandow's argument is that the future health of classical music depends on its maintaining a presence in popular consciousness. He thinks the best way to do this is to package and market it like popular music, encourage more crossover endeavors, and abandon the mindset that classical music is deeper and more artistically meaningful than popular music. I think he's wrong.

Simply put, if you put classical music in competition with popular music on popular music's turf, it loses every time. Popular music has become the prevalent musical culture of our time because there's a lot of money to be made; nobody will ever get (comparatively) rich doing classical music. It's become a commonplace argument that the "decline" of classical music in the second half of the 20th century happened because classical artists abandoned their audience via (take your pick) stuffy formality, over-intellectualization, non-communicative serial music, etc., etc. My own sense is that, outside of the popular media, there's just as much classical music going on today as there was fifty years ago. Classical music isn't on the wane, it's just that popular culture has waxed to an unprecedented degree. And the reasons for that are economic.

Here's my alternate narrative: popular music didn't really become the cash cow it is now until the 1950's—suddenly, post-WWII, teenagers had a lot of disposable income for the first time. They were spending it on popular music (as teenagers have always done), but now, the amount of money they were spending was large enough to attract the attention of individuals and companies who had no inherent interest in the artistic value of the music. They got into the business to make a buck, pure and simple, and that became the driving force in the industry.

In other words, up until the war, all types of music were on a relatively level playing field, financially speaking; there was money to be made, but a) not in a sufficiently unbalanced way to drive entrepreneurs into one type of music over another, and b) not in sufficient amounts to attract non-music-loving capitalists. But once the money became serious, popular music won out. The overhead is less (fewer players means fewer people to pay, as well as cheaper recording costs), the marketing is easier (3-minute blocks of music are an easier sell to advertising-based media than 20-minute blocks), and the possibility for economic exploitation is greater (a far greater emphasis on young, "entry-level" performers translates into a greater corporate share of the profits).

There's also the fact that popular music has lyrics, which means that it's far easier to write and talk about than instrumental classical music. Even today, the vast majority of rock and pop critics can't write about the music in a particularly inspiring way, but they don't have to—they just analyze the words. (I wouldn't mind this if all lyrics were on a Dylan-esque level, but let's face it, not even close.)

Sandow keeps saying that he doesn't want classical music to "dumb down," but all the virtues of classical music—subtlety, intricacy, intellectual engagement, and a grandeur that takes longer than three minutes to build and realize—are at odds with the lowest-common-denominator aesthetic that's the holy grail of popular marketing. Sure, there's popular-style music out there that has a lot of similar virtues, but, like classical music, it's a niche market. And, taken collectively, I think classical music's current niche market is probably larger.

I don't underestimate the need for classical music organizations to market to younger audiences. (Let's just say that the collective accumulated wisdom of a Friday-afternoon Boston Symphony audience is no doubt considerable.) And certainly younger demographics are more media-savvy consumers than classical marketers are used to. But that brings with it a need for the classical world to be that much more honest about what they're offering; if you try and market classical music like popular music, that younger demographic is going to see right through it. At the same time, there's the danger that, in pursuit of a pop-music-sized audience, classical organizations will cross the line between popular marketing and popular aesthetics. The problem with using the marketing trappings of popular culture is that it brings with it the tendency to measure success in the same way: quantity and profitability vs. quality and meaningfulness. Popular culture is beholden to the free market, and the free market is great for determining price, but it's lousy at determining value.

August 13, 2006

"So I can't give you back my heart completely..."

...and I reserve the right to change my mind. The cheatin' hearts in this case belong to a smattering of members on the Nashville Metropolitan Council, who seem to be getting cold feet as the Nashville Symphony's new Schermerhorn Symphony Center walks up the aisle to its scheduled opening. See, the city of Nashville contributed five million dollars a year to the Center last year, and is scheduled to do the same for the next two years, but now said council members are looking to bail on the future part of that commitment. (Article via Arts Journal.) In the words of council member John Summers:

Extra fun! Do a quick 'n' dirty calculation of the economic impact of a local arts organization. (I plugged in some numbers for Nashville, and it would seem that this unsourced claim of a 20-million-dollar impact in the Center's first year is not that pie-in-the-sky.)

“I think the amount of money that’s been committed to the Symphony is excessive, and I think that the administration has not been forthcoming with what their commitment was."—which raises the question of just how forthcoming he would like it to be. I found the commitment clearly spelled out on page 47 of Nashville's 2006-07 proposed Capital Improvements Budget (long PDF from an FTP server that seems to crash Safari; use Firefox). (For perspective, the CIB also has five million dollars earmarked for new concession stands at the Nashville Coliseum.) Here's the kicker: the budget was unanimously approved by the Nashville Metropolitan Council on June 13, 2006. That's right—the naysayers voted for the funding only two months ago. My fickle friend, the summer wind.

Extra fun! Do a quick 'n' dirty calculation of the economic impact of a local arts organization. (I plugged in some numbers for Nashville, and it would seem that this unsourced claim of a 20-million-dollar impact in the Center's first year is not that pie-in-the-sky.)

August 10, 2006

"Yes? Is it about the hedge?"

Comments are always welcome here, but only one can be first; and the guy who claimed Soho the Dog's comment maidenhead has a blog of his own, which anyone reading this should go visit right now. He's a funeral director; if you happen to join the choir invisible in the Southeastern United States, he's your man. (I actually toyed with the idea of being a coroner when I was a kid, so I'm tickled to, well, you know, that my first commenter is an undertaker.)

August 09, 2006

How to make concerts not boring

I was thinking about a piece of music today, and thought I'd procrastinate by trying to track it down. It was a piece my teacher in grad school, Lukas Foss, used to bring up as a good example of a composer being "naughty." ("Naughty" was always a compliment coming from him.)

I did find it -- an 1972 orchestral number called "...No Longer Than Ten (10) Minutes" by the dean of Canadian composers, R. Murray Schafer. The joke was, at least as far as I knew, that the title was taken straight from the legalese in the commission, so Schafer made that the title and, of course, made the piece longer than ten minutes.

Well, that ain't the half of it. This piece, at least on paper, sounds seriously awesome. The Toronto Symphony's practice at the time was to put new music at the beginning of the concert, so subscribers could take comfort in being fashionably late. As Schafer writes:

Needless to say, the result was commotion. Schafer says that, after a couple of rounds from a pre-planted claque, the audience actually caught on to the joke, and kept triggering new crescendos from the percussion. Finally the conductor reappeared and plunged the orchestra into the next piece (not the Brahms; management had gotten wind of Schafer's scheme and rearranged the program). Let Schafer have the last word:

(Quotes are from Schafer's own PDF compendium of program notes for all his works. It's long -- "No Longer Than Ten (10) Minutes" notes start on page 33.)

I did find it -- an 1972 orchestral number called "...No Longer Than Ten (10) Minutes" by the dean of Canadian composers, R. Murray Schafer. The joke was, at least as far as I knew, that the title was taken straight from the legalese in the commission, so Schafer made that the title and, of course, made the piece longer than ten minutes.

Well, that ain't the half of it. This piece, at least on paper, sounds seriously awesome. The Toronto Symphony's practice at the time was to put new music at the beginning of the concert, so subscribers could take comfort in being fashionably late. As Schafer writes:

The management of the [Toronto Symphony] had informed me that the new work would have the distinction of being first on the program “when the audience was fresh.” I determined to screw them up by agglutinating my piece to the next piece on the program so that there would be no opportunity to open the doors between numbers, and late-comers would have to wait outside until the intermission.The piece emerges out of the orchestra tune-up; as the second piece on the program was to be the Brahms B-flat piano concerto, Schafer ended his piece by having the last desk strings sustain a dominant chord (that would be resolved by the opening of the Brahms) with the instruction to keep playing it after the piece was "over," after the conductor left the stage, during the pause, and until the downbeat of the next piece. But wait, there's more:

The climax is reached after a long crescendo precisely at ten minutes. Then the conductor signals the orchestra to cut and turns to leave the stage. But the orchestra continues to hold the last chord, only gradually fading down. Now the instructions are to go back to the beginning of the crescendo if there is applause from the audience and to continue repeating the crescendo to the climax for as long as the applause continues.The longer the audience applauds, the longer the piece goes on.

Needless to say, the result was commotion. Schafer says that, after a couple of rounds from a pre-planted claque, the audience actually caught on to the joke, and kept triggering new crescendos from the percussion. Finally the conductor reappeared and plunged the orchestra into the next piece (not the Brahms; management had gotten wind of Schafer's scheme and rearranged the program). Let Schafer have the last word:

Of course the critics were unkind. They attacked me for being insincere. Not a word about the fraudulence of others. Bang,No recording; as far as I can tell, no repeat performance. According to another source, graphic elements in the score were derived from Vancouver traffic patterns. Sweet Jesus, somebody needs to program this thing.

Schafer gets it right over the head. One critic even suggested that I appeared to be finished as a composer. My poor mother almost believed him.

(Quotes are from Schafer's own PDF compendium of program notes for all his works. It's long -- "No Longer Than Ten (10) Minutes" notes start on page 33.)

August 08, 2006

Manners of speaking

This was nagging at me, so I went back and re-read a bunch of last week's obituaries for Elizabeth Schwarzkopf. They're all about the same: her renown in the 60's and 70's, her shady Nazi past, her EMI career, her husband, her tyrannical teaching style. Oh, and this...

From The New York Times:

... and I suddenly realized that calling a singer "mannered" is just a way of concealing a certain laziness of opinion. (I've done it, too.) Face it: all singing is mannered. You're taking words that would normally be spoken, and singing them -- the amount of moment-to-moment strategizing is enormous. If you're going to take someone to task, though, I think that you need to put in a little more effort than just calling it "mannered." Any singer worth their salt is doing just as much calculation as Schwarzkopf ever did; it's just that, if you buy it, you don't notice it.

From The New York Times:

But others found her interpretations calculated, mannered and arch...From the Boston Globe:

Her syllable-by-syllable highlightings of poetic texts were also notably unspontaneous, leading to repeated charges of affectation and mannerism.From About Last Night:

Yet even at the height of Schwarzkopf’s career, there were plenty of critical naysayers who found her singing fussy and mannered to the point of archness, and since her retirement in 1975, it’s my impression that their point of view, which I share, has come to prevail.

... and I suddenly realized that calling a singer "mannered" is just a way of concealing a certain laziness of opinion. (I've done it, too.) Face it: all singing is mannered. You're taking words that would normally be spoken, and singing them -- the amount of moment-to-moment strategizing is enormous. If you're going to take someone to task, though, I think that you need to put in a little more effort than just calling it "mannered." Any singer worth their salt is doing just as much calculation as Schwarzkopf ever did; it's just that, if you buy it, you don't notice it.

August 07, 2006

Stage Floor Canteen

The Globe reports on the replacement of the stage floor at Symphony Hall. In short: they're going to an awful lot of trouble, mainly because of the floor's "mystical reputation" among musicians for contributing to the overall acoustic of the place.

A show of hands: how many people think that the practical result of this will be a lot of sad head-shaking and pompous murmurs of how it just doesn't sound like it used to? How much less murmuring would have occurred if the BSO had said nothing at all? (It's not like they're replacing maple with stainless steel and bathroom tile.)

This is a familiar trope in classical music coverage, particularly when new halls open -- a review of the acoustic. Complaints about the acoustic. How much money has been spent tweaking the acoustic. Who cares? It's the kind of head-of-a-pin criticism that makes classical music seem like a lot more work than it is. (And makes people insecure about their own ability to hear.)

But what's this?

(Something about Boston and floors.)

A show of hands: how many people think that the practical result of this will be a lot of sad head-shaking and pompous murmurs of how it just doesn't sound like it used to? How much less murmuring would have occurred if the BSO had said nothing at all? (It's not like they're replacing maple with stainless steel and bathroom tile.)

This is a familiar trope in classical music coverage, particularly when new halls open -- a review of the acoustic. Complaints about the acoustic. How much money has been spent tweaking the acoustic. Who cares? It's the kind of head-of-a-pin criticism that makes classical music seem like a lot more work than it is. (And makes people insecure about their own ability to hear.)

But what's this?

"The orchestra has saved the floorboards and plans to polish them, and sell small pieces as mementos and souvenirs."Can I buy the whole floor? I want the most acoustically mystical backyard deck in town!

(Something about Boston and floors.)

Where to Go Next

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)