Music is great because you can put it on the stereo and still do other things. Not so dance, which requires one too many senses for multitasking. I've wasted a good chunk of the morning hunting around YouTube for the work of the French choreographer Maurice Béjart, just for fun; I figure I better just post a few before the whole day is a wash.

Here's a bit of Béjart's 1966 Webern, Opus V, as danced by Loipa Araujo and Jorge Esquivel at the 1969 International Ballet Competition in Moscow. Unfortunately marred by an announcer who has no idea what he's talking about—that w in Webern's name is pronounced like a v, my good man! Maybe I'm biased, but I actually find it pretty romantic.

This two-parter gives a little glimpse of Béjart at work, fashioning his 1973 ballet to Boulez's La marteau sans maître. The primary dancers are Jorge Donn and Rita Poelvoorde. The rehearsal sequences are beautifully lyrical; the finale, from the La Scala premiere, is a little outré out of context, but makes fascinating comparison with the more overt classicism of the 1966 dance.

Béjart has a long history with modernist atonality (both the 1962 Suite viennoise and the 1982 Wien, Wien, Nur du Allein use music of the Second Viennese School; he's also choreographed Stockhausen's Stimmung), but also has a knack for less abstruse sounds. Here's Donn and Poelvoorde again, in a terrifically charming pas de deux from Dichterliebe, choreographed in 1975 to music by Schumann and (the bulk of this excerpt) Nino Rota.

And now my procrastination is yours.

May 31, 2007

May 30, 2007

Oldies compilation

Today's time-sink is the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music (free registration required), a joint project of the University of Oxford and Royal Holloway, University of London, consisting of fantastically high-resolution (144 megapixels) images of manuscript sources for Medieval and Renaissance polyphony.

From Oxford's Bodleian Library (MS. Don. b. 31), an Agnus Dei with the incipit beautifully encased in the initial Q of "qui."

From Oxford's Bodleian Library (MS. Don. b. 31), an Agnus Dei with the incipit beautifully encased in the initial Q of "qui."

Three successive initials on page 54 (verso) of MS 178 from the Eton College Library. I love how the obviously Irish scribe indulges himself on that third one.

Three successive initials on page 54 (verso) of MS 178 from the Eton College Library. I love how the obviously Irish scribe indulges himself on that third one.

And from the British Library (Egerton 3307), a Medieval house party. Even the dogs and monkeys are getting drunk. Rock-band excess has nothing on the fifteenth century.

And from the British Library (Egerton 3307), a Medieval house party. Even the dogs and monkeys are getting drunk. Rock-band excess has nothing on the fifteenth century.

The sources archived include all the fragmentary sources of polyphony up to 1550 in the UK (and almost all of these are available for study through this website); all the ‘complete’ manuscripts in the UK; a small number of important representative manuscripts from continental Europe; a significant portion of fragments 1300-1450 from Belgium, France, Italy, Germany and Spain.Obviously a great resource for scholars (they've started to include images taken under ultraviolet light as well), but also surprisingly fun to just browse around. It takes some time—the search functions are geared towards experts trying to pinpoint particular manuscripts or collections—but there's plenty of graphic treasure to be found. Here's a few favorites:

From Oxford's Bodleian Library (MS. Don. b. 31), an Agnus Dei with the incipit beautifully encased in the initial Q of "qui."

From Oxford's Bodleian Library (MS. Don. b. 31), an Agnus Dei with the incipit beautifully encased in the initial Q of "qui." Three successive initials on page 54 (verso) of MS 178 from the Eton College Library. I love how the obviously Irish scribe indulges himself on that third one.

Three successive initials on page 54 (verso) of MS 178 from the Eton College Library. I love how the obviously Irish scribe indulges himself on that third one. And from the British Library (Egerton 3307), a Medieval house party. Even the dogs and monkeys are getting drunk. Rock-band excess has nothing on the fifteenth century.

And from the British Library (Egerton 3307), a Medieval house party. Even the dogs and monkeys are getting drunk. Rock-band excess has nothing on the fifteenth century.

May 29, 2007

We'll Meet Again

There's been an interesting mini-trend in operatic directing in the past few months: updating 19th-century comic operas to World War II settings. Emilio Sagi's WWII La Fille du Regiment, originally produced in Bologna, had notable revivals at La Scala and in Washington (it comes to Houston later this year); here in Boston, the Boston Conservatory's spring production of "L'elisir d'amore" had a WWII setting, as did Intermezzo's Signor Deluso; and now Marc Geelhoed sends word of Chicago Opera Theater's Béatrice et Bénédict.

In general, I'm more sympathetic to high-concept modernizations of opera than most. Bad ones just vaguely toy around with making the piece "relevant" or other such nonsense, but good ones are after bigger game: the immediacy of the dramatic situation. One of my favorite modernizations was Peter Sellars' 1988 Tannhäuser for the Chicago Lyric Opera, with the title character a fallen televangelist in the Jim Bakker mold. The production was a scandal, mainly to those who already knew the piece; but for those of us who didn't (including me, at that time), it made the dramatic stakes immediately apparent, rather than something in need of explanation or exposition. (For those who remember the staging with disdain, I'll simply defend it by saying that it got me interested in Tannhäuser, and Tannhäuser is the opera that got me interested in Wagner.)

I charitably assume that directors with similar ideas are after the same thing, rather than mere novelty or shock. A rather charitable assumption, in many cases, but if we apply it to this latest spate of 1940s military imagery, what does it mean? It means the directors are sure that, as soon as we recognize the setting, we'll be put in the proper frame of mind for light romantic comedy. Which is pretty weird, when you think about it.

I would think that, after the last century's carnage, we would be pretty immune to the romanticization of war, but I guess these days, historically hung over from Vietnam, mired in Iraq, the perception of nobility and moral clarity offered by World War II has become more and more appealing. Of course, that conflict had as much ignobility and moral ambiguity as any. (Ponder the Allied response to the Holocaust, or the internment of Japanese-Americans. I'm not implying a blanket condemnation of our reactions in those situations, but just offering an example of how wartime is always messier and more complicated than we like to remember.) And WWII vets had the same difficulties readjusting to civilian life, something that was more readily discussed at the time than it is now. (Case in point: William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives, released in 1946 to critical acclaim.)

And yet, the 60 intervening years have made that event not only comparatively benign, but a suitable backdrop for some of the sunniest operas in the repertory. It's worth noting that nobody (myself included) has experienced these productions as cognitively dissonant, or somehow trying to directorially inject a note of bleak despair. I think what they're tapping into is that peculiar historical moment, when it seemed that, for all the cascading political complications as the war ended, the Allied cooperation and the lessons of 1919 would ensure that the brave new post-war world would really be a better place. Romantic comedies are, after all, essentially optimistic; I guess the level of underlying poignancy depends on how well you know your history.

In general, I'm more sympathetic to high-concept modernizations of opera than most. Bad ones just vaguely toy around with making the piece "relevant" or other such nonsense, but good ones are after bigger game: the immediacy of the dramatic situation. One of my favorite modernizations was Peter Sellars' 1988 Tannhäuser for the Chicago Lyric Opera, with the title character a fallen televangelist in the Jim Bakker mold. The production was a scandal, mainly to those who already knew the piece; but for those of us who didn't (including me, at that time), it made the dramatic stakes immediately apparent, rather than something in need of explanation or exposition. (For those who remember the staging with disdain, I'll simply defend it by saying that it got me interested in Tannhäuser, and Tannhäuser is the opera that got me interested in Wagner.)

I charitably assume that directors with similar ideas are after the same thing, rather than mere novelty or shock. A rather charitable assumption, in many cases, but if we apply it to this latest spate of 1940s military imagery, what does it mean? It means the directors are sure that, as soon as we recognize the setting, we'll be put in the proper frame of mind for light romantic comedy. Which is pretty weird, when you think about it.

I would think that, after the last century's carnage, we would be pretty immune to the romanticization of war, but I guess these days, historically hung over from Vietnam, mired in Iraq, the perception of nobility and moral clarity offered by World War II has become more and more appealing. Of course, that conflict had as much ignobility and moral ambiguity as any. (Ponder the Allied response to the Holocaust, or the internment of Japanese-Americans. I'm not implying a blanket condemnation of our reactions in those situations, but just offering an example of how wartime is always messier and more complicated than we like to remember.) And WWII vets had the same difficulties readjusting to civilian life, something that was more readily discussed at the time than it is now. (Case in point: William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives, released in 1946 to critical acclaim.)

And yet, the 60 intervening years have made that event not only comparatively benign, but a suitable backdrop for some of the sunniest operas in the repertory. It's worth noting that nobody (myself included) has experienced these productions as cognitively dissonant, or somehow trying to directorially inject a note of bleak despair. I think what they're tapping into is that peculiar historical moment, when it seemed that, for all the cascading political complications as the war ended, the Allied cooperation and the lessons of 1919 would ensure that the brave new post-war world would really be a better place. Romantic comedies are, after all, essentially optimistic; I guess the level of underlying poignancy depends on how well you know your history.

May 28, 2007

Scherzando

Terry Teachout throws down a nice challenge today: name a great Hollywood film score written for a comedy. Tough, because, like so much else about comedy, if you notice the score, it's not really doing its job. Comedy is all about efficiency—film scoring is all about luxury. For a comedic one to work, the effort has to be imperceptible.

For an example, let's examine what I think is one of the all-time best comedy film scores: Franz Waxman's for The Philadelphia Story. The first thing you notice is that it's hardly there at all—maybe twenty minutes of music, and that includes some ambient Cole Porter arrangements for the big party scene. Which leaves, what? Ten minutes of actual cues? Maybe less? Yet without those ten minutes, the movie doesn't work at all.

Take the opening scene, a flashback in which Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant acrimoniously end their marriage. She breaks his golf clubs; he winds up to punch her, and instead puts his hand over her face and pushes her to the ground. Pretty tough start for a guy we're supposed to spend the rest of the movie rooting for. Waxman smooths it over with pure cartoon music, mickey-mousing every bit of action with imitative instrumentation. Not only does it decisively confirm the scene as slapstick, it reassures us that the main dramatic conflict is not serious enough to turn into drama. Waxman doles out a little more of the same later, when, depressed and confused, Hepburn downs an entire tray of champagne saucers. Incipient alcoholism? Nah—the insouciantly echoing clarinet line slyly signals that it's the beginning of her salvation.

Waxman brings his full romantic arsenal to bear in only one scene, the late-night dance between Hepburn and Jimmy Stewart—and even here, he sneaks in, ingeniously dovetailing the cue with some languid jazz coming from an on-screen radio. That's his strategy all the way through: slip into the scene, gently tip it in the right dramatic direction, and then slip out again.

Big, epic comedies can produce great scores (John Williams' underrated score for 1941 springs to mind), but such scores are usually forgotten because the resulting movies almost never work. (I'm racking my brains to come up with an example of one that does, and the only one I can think of is Ghostbusters, in which Elmer Bernstein's Stripes-redux score jostles for space with a lot of 80s pop.) Interestingly, some of my favorite music for comedies is pre-existing: Scott Joplin rags in The Sting, Carmen in the original Bad News Bears, the Marriage of Figaro overture in Trading Places. Lisa Hirsch nominates the collective work of Warner Brothers animation composer Carl Stalling—divorced from the films, the music does have a modernist, fragmentary musique concréte energy, but that's a response to the structure of the visuals, not an inherently musical inspiration. Alex Ross suggests Danny Elfman's score for Beetlejuice—I'd go back farther to Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, Elfman's first score and still one of the best things he's ever done, a pitch-perfect musical embodiment of the movie's loopy atmosphere. I searched high and low for that soundtrack, and when I found it, I wore it out.

That's the exception, though. I remember a few years back, when the Modern Library came up with their list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the last century. I was ticked that the Julia Child-Louisette Bertholle-Simone Beck Mastering the Art of French Cooking didn't make the list, but really, the elegance and wit of that book's writing will always take a perceptive backseat to its functionality. That's what good comedy scores are like: ideally stylish, but necessarily efficient.

The readers, blessedly more intelligent than me, have posted many a fine comment.

For an example, let's examine what I think is one of the all-time best comedy film scores: Franz Waxman's for The Philadelphia Story. The first thing you notice is that it's hardly there at all—maybe twenty minutes of music, and that includes some ambient Cole Porter arrangements for the big party scene. Which leaves, what? Ten minutes of actual cues? Maybe less? Yet without those ten minutes, the movie doesn't work at all.

Take the opening scene, a flashback in which Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant acrimoniously end their marriage. She breaks his golf clubs; he winds up to punch her, and instead puts his hand over her face and pushes her to the ground. Pretty tough start for a guy we're supposed to spend the rest of the movie rooting for. Waxman smooths it over with pure cartoon music, mickey-mousing every bit of action with imitative instrumentation. Not only does it decisively confirm the scene as slapstick, it reassures us that the main dramatic conflict is not serious enough to turn into drama. Waxman doles out a little more of the same later, when, depressed and confused, Hepburn downs an entire tray of champagne saucers. Incipient alcoholism? Nah—the insouciantly echoing clarinet line slyly signals that it's the beginning of her salvation.

Waxman brings his full romantic arsenal to bear in only one scene, the late-night dance between Hepburn and Jimmy Stewart—and even here, he sneaks in, ingeniously dovetailing the cue with some languid jazz coming from an on-screen radio. That's his strategy all the way through: slip into the scene, gently tip it in the right dramatic direction, and then slip out again.

Big, epic comedies can produce great scores (John Williams' underrated score for 1941 springs to mind), but such scores are usually forgotten because the resulting movies almost never work. (I'm racking my brains to come up with an example of one that does, and the only one I can think of is Ghostbusters, in which Elmer Bernstein's Stripes-redux score jostles for space with a lot of 80s pop.) Interestingly, some of my favorite music for comedies is pre-existing: Scott Joplin rags in The Sting, Carmen in the original Bad News Bears, the Marriage of Figaro overture in Trading Places. Lisa Hirsch nominates the collective work of Warner Brothers animation composer Carl Stalling—divorced from the films, the music does have a modernist, fragmentary musique concréte energy, but that's a response to the structure of the visuals, not an inherently musical inspiration. Alex Ross suggests Danny Elfman's score for Beetlejuice—I'd go back farther to Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, Elfman's first score and still one of the best things he's ever done, a pitch-perfect musical embodiment of the movie's loopy atmosphere. I searched high and low for that soundtrack, and when I found it, I wore it out.

That's the exception, though. I remember a few years back, when the Modern Library came up with their list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the last century. I was ticked that the Julia Child-Louisette Bertholle-Simone Beck Mastering the Art of French Cooking didn't make the list, but really, the elegance and wit of that book's writing will always take a perceptive backseat to its functionality. That's what good comedy scores are like: ideally stylish, but necessarily efficient.

The readers, blessedly more intelligent than me, have posted many a fine comment.

Помните

In honor of Memorial Day, here's the finale of Dmitri Kabalevsky's 1963 Requiem, "for those who died in the war against fascism."

Kabalevsky: Requiem (Finale: "Pomnite!") (mp3, 7.2 Mb)

Valentina Levko, contralto; Vladimir Valaitis, baritone

Moscow Chorus

Children's Chorus of the Art Education Institute

Moscow Philharmonic, Dmitri Kabalevsky, conductor

Kabalevsky (1904-1987) said that he dreamed for years of writing this piece; I don't doubt that, but, given the timing, it's hard not to hear his Requiem as some sort of Soviet response to Benjamin Britten's War Requiem of 1962. Coincidence or not, it's a classic example of a good piece of music being overshadowed by a similar, great piece. Kabalevsky's music is undeniably effective, and often inspired, but his socialist-realist vocabulary precludes any of the questioning of pro patria mori that produces such crackling tension in the Britten, and Kabalevsky's text (by poet Robert Rozhdestvensky), while solidly dramatic, can't compare with the combination of Wilfred Owen and the timeless Latin of the Mass (which, of course, Kabalevsky eschews). But if all you know of Kabalevsky is the overture to The Comedians and some of his often-anthologized piano pieces, the Requiem is worth a listen. And it's hard to argue with the climax:

Kabalevsky: Requiem (Finale: "Pomnite!") (mp3, 7.2 Mb)

Valentina Levko, contralto; Vladimir Valaitis, baritone

Moscow Chorus

Children's Chorus of the Art Education Institute

Moscow Philharmonic, Dmitri Kabalevsky, conductor

Kabalevsky (1904-1987) said that he dreamed for years of writing this piece; I don't doubt that, but, given the timing, it's hard not to hear his Requiem as some sort of Soviet response to Benjamin Britten's War Requiem of 1962. Coincidence or not, it's a classic example of a good piece of music being overshadowed by a similar, great piece. Kabalevsky's music is undeniably effective, and often inspired, but his socialist-realist vocabulary precludes any of the questioning of pro patria mori that produces such crackling tension in the Britten, and Kabalevsky's text (by poet Robert Rozhdestvensky), while solidly dramatic, can't compare with the combination of Wilfred Owen and the timeless Latin of the Mass (which, of course, Kabalevsky eschews). But if all you know of Kabalevsky is the overture to The Comedians and some of his often-anthologized piano pieces, the Requiem is worth a listen. And it's hard to argue with the climax:

| Lyudi zemli,— ubeite voinu! Lyudi zemli, proklyanite voinu! No o tekh, kto uzhe ne pridyot nikogda,— zaklinayu,— pomnite! | People of the world— kill war! People of the world, curse war! But them who will never come back— I beseech you— remember! |

May 25, 2007

Let It Snow

Today's the first really hot day we've had here in Boston this year—projected high of 91º F, a record for the day. For you all in the South and Southwest who are thinking to yourself 91? That's not even close to hot, I confess: I'm a cold weather person, and once it gets above 75, I start to wilt. (I was telling my dentist this yesterday, and he theorized that I was an Eskimo orphan and my parents never told me.)

Anyway, I started thinking about good records to put on to take one's mind off of the heat, and I realized: I think of those in two categories. There's naturally cold music that, to me, conjures the illusion of arctic wastelands or snow-covered bare trees or iced-over rivers. Here's a few—some are obvious, some not.

Vaughan Williams: Symphony no. 7, Sinfonia antartica Sibelius: Symphony no. 5 Shostakovich: Symphony no. 14 Feldman: Piano and String Quartet Grieg songs David Bowie: Low Scelsi: I presagi

My lovely wife says, for her, the orchestral versions of Strauss's "Ruhe, meine Seele" and "Allerseelen," along with Wolf lieder in minor keys, produce a nice chill.

But then, there's an entirely separate category of music that is like air-conditioning—a sleek, technological cool that's self-contained and unfailingly comfortable.

Gershwin: concert works Debussy: Nocturnes Webern: Concerto, op. 9 Miles Davis: Kind of Blue Elvis Costello and the Attractions: Punch the Clock Adams: Nixon in China, act 3 Stravinsky: Movements

I'm a child of American excess: Concerto in F and "So What" it is. It's a long weekend: any other suggestions? (Particularly on the pop side—I had to think to come up with those two examples.)

Anyway, I started thinking about good records to put on to take one's mind off of the heat, and I realized: I think of those in two categories. There's naturally cold music that, to me, conjures the illusion of arctic wastelands or snow-covered bare trees or iced-over rivers. Here's a few—some are obvious, some not.

My lovely wife says, for her, the orchestral versions of Strauss's "Ruhe, meine Seele" and "Allerseelen," along with Wolf lieder in minor keys, produce a nice chill.

But then, there's an entirely separate category of music that is like air-conditioning—a sleek, technological cool that's self-contained and unfailingly comfortable.

I'm a child of American excess: Concerto in F and "So What" it is. It's a long weekend: any other suggestions? (Particularly on the pop side—I had to think to come up with those two examples.)

May 24, 2007

I've Got You Under My Skin

A request: I'm working on a follow-up to this tattoo post from a few weeks back. If you're a classical musician with body art, or have a classical-related design, I'd love to hear from you: use the e-mail address at the bottom of the sidebar.

I keep a stiff upper lip and I shoot from the hip

I'm running all over town today, but here's some stories from the UK to keep you entertained.

Sympathy for Charlotte Harding, an 18-year-old from Yorkshire who traveled to the University of St. Andrews to hear their symphony give the premiere of her new saxophone concerto, only to have it drowned out by a nearby party.

In other news, a longtime friend of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, who happens to be married to Maxwell Davies' manager, has been arrested for allegedly embezzling 500,000 pounds from the Master of the Queen's Music.

The other big story over there involves photos of Hitler taken at the 1939 Bayreuth Festival by Charles Turner, a composer who was also working for British intelligence.

And finally, this. Note: playing "Memory" in the background while you read it really enhances the effect.

Sympathy for Charlotte Harding, an 18-year-old from Yorkshire who traveled to the University of St. Andrews to hear their symphony give the premiere of her new saxophone concerto, only to have it drowned out by a nearby party.

The noise pollution came from an event run by the Lumsden Club, an "elite ladies" society that prides itself on social and charity parties, which was staging a noisy fund-raiser nearby.... "It was all right when the orchestra played loudly but, during the quieter bits of music, you couldn't hear anything but the disco," said [Harding's mother].So the performance was disrupted by a prom that came through a wormhole from the year 1987? I never want to hear classical music described as outdated and living in the past again.

...

The club's website states: "We host fun social and charity events throughout the university calendar and make a difference within the community." The poster for a coming Top Gun Night features a sexy photo of Tom Cruise and the dress code is "Take My Breath Away".

In other news, a longtime friend of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, who happens to be married to Maxwell Davies' manager, has been arrested for allegedly embezzling 500,000 pounds from the Master of the Queen's Music.

Michael Arnold, 73, husband of Judy Arnold, the composer’s manager for 32 years, was taken to Notting Hill Police Station for questioning about money allegedly missing from Sir Peter’s business account.... The Arnolds are close friends and he has in the past dedicated compositions to them. His music is even catalogued in what he calls J Numbers, named after Judy Arnold. Mr Arnold is said to look after his financial affairs.This is playing Covent Garden within five years, I guarantee it. (It's all over the UK papers, but I've linked to the Times report on the strength of its first reader comment.)

The other big story over there involves photos of Hitler taken at the 1939 Bayreuth Festival by Charles Turner, a composer who was also working for British intelligence.

It is believed that Mr Turner was one of the last Britons to speak face to face with the Nazi dictator before the outbreak of the conflict. The record of what words passed between the two men is locked away in the vaults of MI5, deemed too sensitive to be declassified. The Home Office has said the document may never be made public.The photos were released to the public by Turner's son, who also remembers driving around Moscow with his father, looking for Kim Philby's apartment. I can't find a whit of information on Turner, which means he must have been pretty good at his day job. (Anybody know any of his music?)

The German-speaking Turner, from Nottinghamshire, had been granted unprecedented access to the Führer and his entourage, which included Joseph Goebbels and Rudolf Hess. The photographer was hosted by the chairman of the Bayreuth chamber of commerce, who was a member of Hitler's inner circle - as was British-born Winifred Wagner, the composer's widow.

And finally, this. Note: playing "Memory" in the background while you read it really enhances the effect.

May 23, 2007

Come On Everybody

Erna Sack and Johannes Heesters in Nanon (1938).

I've been experimenting with transferring 78 rpm records to the computer; here's a couple of sides from the legendary German coloratura soprano Erna Sack.

Johann Strauss, Jr:

"On the Beautiful Blue Danube" (mp3, 4.2 MB)

"Voices of Spring" (mp3, 4.3 MB)

One of the main things Sack was legendary for was her high C. And not that high C, but the one an octave up—five ledger lines above the treble staff, if you're keeping score at home. She deploys it at around the 2:38 mark of "Voices of Spring"; the same riff, slightly lower, also turns up at the end of "The Blue Danube." (To my ear, it sounds closer to a B, but given the vagaries of recording and playback speeds, I'll give it to her. B would be crazy enough.)

If I was coaching a soprano with those kinds of notes, I probably wouldn't begrudge her interpolating them wherever even just barely reasonable; if you got 'em, might as well use 'em. But if I was composing for the same soprano, would I build the piece around those notes? Nope—I'd certainly leave room for some ossia high-wire acrobatics, but I'd first make sure the music was maximally effective without them. Here's why: I like the idea of notation. And to notate a piece that only one person would probably ever perform defeats the purpose, in my mind.

In a more detailed way, it's about the difference between a piece of music as a series of sounds and as a set of notated instructions. I'm as fascinated by the latter as the former, not because I'm disinterested in sound, or devoted to augenmusik, but because I think that the translation from sound into notes and back into sound again is one of the most magical aspects of composition. There's a slippery vagueness inherent in each step of that progression that's the essence of the compositional challenge: designing a situation that allows for the greatest chance of an interpretive lightning strike without degenerating into diffuse aimlessness, or, on the other side, stifling precision. The exact position of those thresholds vary from piece to piece, and from composer to composer; under the right circumstances, everything from indeterminacy to total serialism can be effective. That's the nature of notation: any notation at all is structuring the performance, but even the most fanatically detailed notation is necessarily incomplete.

For me, to structure a piece around the unique abilities of one particular performer closes that door. It's not that I'm trying to make my music technically easier—far from it, in some cases. (And I've paid the price.) And I like writing for performers I know, keeping their personalities and particular sound in mind as I imagine the piece. But I make sure that, down the line, someone else should be able to pick up the same piece and make a go of it. The life of the music isn't on the page, or even in the initial realization: it's the possibility of other performers being able to take the same notes and, using their own sound and their own experience, make something brand-new out of them, something I hadn't considered, something the original players hadn't considered, creating a performing tradition for the music that's not a set of rigid guidelines, but a fluid range of possibility that each subsequent interpreter can explore and expand.

That's just my opinion—the advent of recording has opened up the possibility of the complete opposite approach, fixing an irreproduceable musical event for anyone to experience, at any time. I've dabbled with that on occasion in the form of electronic and sequenced computer music, and that ability to tweak and refine to your heart's content could very well be a crucial element of the success of a work, depending on the ultimate goal. But I'm still too addicted to the thrill of hearing notes that only existed in my head suddenly conjured into existence, running out into the world, taking on a life of their own.

May 22, 2007

Second Deal

Reviewing the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston.

Boston Globe, May 22, 2007.

Boston Globe, May 22, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

May 21, 2007

Line Dance

Our librarian friend Rebecca Hunt (really, all of you should have a librarian friend) alerts us to the launch of the online Juilliard Manuscript Collection, lovely digital images of the trove donated to the school last year by their board chairman, Bruce Kovner. Lots of serious, scholarly stuff here—autographs, sketches, composer-corrected proofs—but, this blog being what it is, we'll skip the serious and scholarly and head straight to these two drawings of Aaron Copland that Leonard Bernstein saw fit to add to the manuscript of his piano arrangement of El Salón México.

May 18, 2007

Rock-and-roll is here to stay

Previewing the Boston Modern Orchestra Project.

Boston Globe, May 18, 2007.

Some bits that didn't make it into the article:

Anthony De Ritis on quoting Ravel's Bolero in his concerto for DJ, Devolution:

(It's new-music day in the Globe: also check out David Weininger on Harold Shapero's new song cycle.)

Boston Globe, May 18, 2007.

Some bits that didn't make it into the article:

Anthony De Ritis on quoting Ravel's Bolero in his concerto for DJ, Devolution:

I actually had finished the piece before I found out [Bolero] wasn't in the public domain. Luckily, many thousands of dollars in lawyers' fees later, I was able to use it.Steven Mackey on the origin of his patriotism:

I remember, I was England for a time as a kid—my father worked for the government—and people would find out we were American, and they'd come up to us and say, "Congratulations on your John Glenn!" or, "Congratulations on winning World War II!" That probably wouldn't happen today.Mackey on rehearsals for the 2003 premiere of Dreamhouse, during which the orchestra found out it was being disbanded:

It was literally, the manager came up and said "I just have to make a couple announcements before we start" and then he gets up in front and says, "Um, you're all fired. Oh, and here's your guest conductor for the week, Gil Rose." It was insane.Excerpt of my interview with Evan Ziporyn:

EZ: There's rock music in [Hard Drive], but it's kind of a narrow segment of that, because it's the music I listened to as a kid, you know? And it's not always what you expect. I liked prog rock—I liked King Crimson, I liked the Mahavishnu Orchestra. But I was also listening to Barry White.

MG: You know, I was a closet Barry White fan for years, and then one day it was like all of a sudden it was cool to be a Barry White fan.

EZ: His time has come!

MG: I've noticed these days that people are pretty shameless about what they like. They don't care if it's cool anymore; the nerdier the better. It's like they wear it as a badge of honor.

EZ: Well, that's a positive development for the human condition, isn't it?

(It's new-music day in the Globe: also check out David Weininger on Harold Shapero's new song cycle.)

Labels:

Globe Articles

May 17, 2007

Sing for your supper

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) loved music, but he thought the joys of harmony paled next to the pleasures of the table. The famed author of Physiologie du Goût (The Physiology of Taste) and the honoree of Brillat-Savarin cheese (a triple-crême, 75% butterfat masterpiece), was a lawyer by trade, but also a musician—during a brief exile to the Untied States during the Reign of Terror, he taught violin and was good enough himself to play first violin in a New York theater orchestra. In his book, Brillat-Savarin regarded hearing a more subtle mechanism than taste:

Taste is not so richly endowed as hearing; the latter can appreciate and compare many sounds at the same time; but taste, on the other hand, is actually simple—that is to say, that two flavours at one are equally inappreciable.But the complete satisfaction of the gourmand is superior, and has superior side-benefits.

But it may be doubled and multipled in succession—that is to say, that in one act of deglutition we may experience successively a second and even a third sensation, each of which gradually becomes more weak, and which are described by the words after-taste, bouquet, or fragrance. So, when a chord is struck, a skilful ear may distinguish one or many series of consonances, of which the number is as yet imperfectly known.

A married pair of gourmands have at least once a day a pleasant opportunity of meeting, for even those who have separate bedrooms—and in France there are a great number who have—eat at least at the same table, and have a subject of conversation which is always new; they speak not only of what they eat, but also of what they have eaten, what they will eat, what they have seen elsewhere, of fashionable dishes, new inventions, and so forth. Everyone knows that such a familiar chit-chat is delightful.Still, it was music that saved his life. Brillat-Savarin had to travel to see one citoyen Prôt, in order to obtain a passport, "which, probably, might save me from prison or the scaffold."

Music, no doubt, has powerful attractions for those who love it; but one must set about it:—it is an exertion.

Besides, sometimes one has a cold, our music is mislaid, the instruments are out of tune, we may have a headache:—there is a strike.

On the other hand, a common want brings the couple to table; the same inclination retains them there; they naturally show each other those trifling attentions which denote a wish to oblige, and their behavior at meal-time has a great share in the happiness of their lives.

I am not one of those persons who are rendered cruel from fear, and I think that M. Prôt was not exactly a bad man; but he was not very intelligent, and he did not know how to employ the formidable power put in his hands; he was like a child armed with the club of Hercules.Having saved his neck in a most quintessentially French manner, Brillat-Savarin survived the Terror, returned to France, and wrote the book for which he became justly famous. In addition to that delectable cheese, he also lent his name to a cake: a savarin nowadays refers to any liqueur-soaked yeast cake without raisins (which would turn it into a baba au rhum). Eat well.

...

I was a little better received by Madame Prôt, to whom I went to pay my repects; for the circumstances under which I presented myself interested at least her feelings of curiosity.

The first words she said were to ask me if I loved music. What an unexpected happiness! She was passionately fond of it, and as I am myself a very fair musician, out hearts beat in unison from that very moment.

...

After supper, she sent for some of her music-books. She sang, I sang, we sang. I never used my voice to greater advantage, and I never enjoyed it more. M. Prôt had already several times said he was going, but she took no notice of it, and we were giving in grand style the duet from [Grétry's] opera la Fausse Magie,"Vous souvient-il de cette fête?"

when he told her he really must insist upon her leaving.

We had to finish; but at the moment of parting, Madame Prôt sait to me, "Citizen, a man who cultivates the fine arts as you have done, does not betray his country. I know you have asked some favor from my husband; it shall be granted; it is I who promise you."

...

Thus the object of my journey was accomplished. I returned home with my head erect; and, thanks to Harmony, charming daughter of Heaven, my ascension was for a good many years postponed.

May 16, 2007

Homage to Walter Busterkeys

We don't usually do birthdays on this blog, but we'll make an exception for Liberace, who would have turned the exquisitely appropriate age of 88 today. I'm not sure that anyone who wasn't alive during Liberace's heyday realizes just how big a star he was—headlining his own TV show at various times throughout his career, guest-starring on every show imaginable (Batman! Kojak! The Monkees!), even venturing into movies now and again. (He's memorably good in his one non-piano role, as the casket salesman in Tony Richardson's The Loved One.) In the 1980s, he sold out two famous runs of shows at Radio City Music Hall, and was pulling down $300,000 a week in Vegas. For playing the piano.

Well, more than that, obviously: the outfits, the jewelry, the mirror-mosaic piano cases, the Rolls-Royce that drove him onstage—the spectacle always in effective counterpoint to his relaxed and easy stage demeanor, fully enjoying the absurdity of his flamboyance with coy self-deprecation. But the man could play. Liberace honed his technique with Florence Bettray-Kelly (herself a student of Moriz Rosenthal), and was good enough to solo with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Frederick Stock as a 14-year-old. This clip shows his way with Chopin—the arrangement, combining the "Minute" Waltz and the A-flat Polonaise, is an abomination, but it's Chopin's notes, for the most part, and Liberace shows some nice limpid fingerwork as well as a real feel for the style. (Had he not opted for glitz, Liberace probably would have been a Chopin specialist in the tradition of Paderewski, his childhood idol; family legend has the old master personally encouraging the young Liberace during a visit to Milwaukee.)

Here's a couple more clips: this performance of "Mack the Knife," from a 60s episode of the Dean Martin Show, is shameless and scintillating in equal measure, and you get to see just what a good time he's having putting the tune through its paces. (The mash-up of Weill with Strauss is a superb musical pun.) And here he is in Vegas, in unusually fine technical form, spinning a surrealistically-juxtaposed medley—"As Time Goes By," "Chopsticks," and "Send In the Clowns."

I sometimes wonder if, had he been born a century earlier, Liberace would have been grouped in with such Romantic virtuosi as Liszt and Alkan. I would imagine that an actual Liszt recital was probably closer to a Liberace show than we think. (Ken Russell thought so, too: his gleefully anachronistic, over-the-top version of the composer in Lisztomania [warning: NSFW backstage toplessness—concert starts at 4:28 mark] owes as much to Liberace as it does to psychedelic-rock excess.)

The image at the top is the cover of a collection I found at Bookman's Alley a while back, and the arrangements are a cut above similar folios I have by the likes of Frankie Carle and Eddy Duchin, who tended to dilute the technical challenges of their style for the popular sheet-music market. Not Liberace: these versions are lush and tricky, with some sweet harmonic substitutions and effective use of 19th-century textures and flourishes. Here's Liberace's arrangement of the Jack Lawrence-Walter Gross standard "Tenderly" (click on each page to enlarge):

Here's my rendition of it. I'm no Liberace; for one thing, he kept his pianos tuned. But, yes, it's as much fun to play as it sounds.

May 15, 2007

Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene

So there's this website called MyHeritage.com, and they've got this face recognition program, word of which has been going around the Internet. Basically, you're supposed to plug in your picture, and they'll tell you which celebrities you most resemble. I'm not sure how accurate it is—one of my top matches was Jacky Cheung. Flattering, but, um, no. Still, I figured I'd let it take a whack at casting the big-budget Hollywood musical about the Second Viennese School I've always dreamed of. Here's what it came up with. No fooling.

I'd definitely pay—what is it now? Nine-fifty?—to see that. I can't wait for the scene where, after the disastrous test screening of Pierrot Lunaire, Webern saves the day by coming up with the idea of having Berg dub Jean Hagen's vocals.

Arnold Schwarzenegger as Arnold Schoenberg

Felicity Huffman as Alban Berg

Billie Joe Armstrong as Anton Webern

I'd definitely pay—what is it now? Nine-fifty?—to see that. I can't wait for the scene where, after the disastrous test screening of Pierrot Lunaire, Webern saves the day by coming up with the idea of having Berg dub Jean Hagen's vocals.

Negotiations and Love Songs

Reviewing Intermezzo Opera.

Boston Globe, May 15, 2007.

Boston Globe, May 15, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

You're not getting any work done today

Other Minds, the epitome of Left Coast new-music fun, has launched radiOM, an online clearing-house for archival recordings from Other Minds-produced concerts and experimental programs from Berkley's KPFA radio. (The announcement was timed to coincide with Lou Harrison's 90th birthday, of course.) As I write, I'm grooving to a 1965 John Cage-David Tudor performance of Christian Wolff's "For 1, 2, or 3 people, any instruments" recorded at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Hours of entertainment for the whole family—4,500 hours, to be exact. That's enough listening to get you to Thanksgiving.

May 14, 2007

Off to see the Wizard

I had a good idea for a post over the weekend. I still have it; I sat down to write it last night and ended up spending the entire evening surfing for Harold Arlen songs. Well, that's a good idea for a post, too.

Here's a 1950s Arlen song, "I Never Has Seen Snow," from a criminally obscure Broadway show called House of Flowers that he co-wrote with a young Truman Capote. (This is from a Boston Pops telecast; even if you're not a Vanessa Williams fan, Martha Babcock's cello solo makes it all worthwhile.)

My favorite Arlen songs are the blues- and gospel-flavored numbers he primarily produced with lyricists Ted Koehler and Johnny Mercer. Arlen and Mercer penned a drawerful of gems for a World War II cinematic revue called Star-Spangled Rhythm—the only one to achieve standard status was "That Old Black Magic" (choreographed for the film by George Balanchine; Hollywood used to be a classy place), but some more military-themed songs are priceless, including the brilliant "I'm Doing It For Defense" and the deliciously-titled "He Loved Me Till the All Clear Came." Here's a clip from the movie: sit through 30 seconds of clumsy framing story featuring a Preston Sturges cameo, and you'll be rewarded with Dick Powell and Mary Martin easing their way through "Hit the Road to Dreamland." Those singing waiters? That's the one-and-only Golden Gate Quartet, one of the greatest gospel groups of all time.

Arlen and Koehler achieved immortality with "Stormy Weather," one of dozens of songs they wrote throughout the 30s for such revues as the Cotton Club Parade and Earl Carroll's Vanities. "When the Sun Comes Out" dates from 1940, and it's a beauty. The late, great Barbara McNair just plain sings the hell out of it.

Arlen is a composer I didn't really appreciate until I started accompanying musical theater students. I think you have to physically get your hands on the music before you discover how creative and audacious he is—he's constantly toying with odd phrase lengths, tricky polyrhythmic syncopations, and slippery harmonies that you don't notice as a listener because his feel for the overall style is so suave. That might be why, even though so much of his musical vocabulary is immediately recognizable, he never had as high a profile as some of his more publicly celebrated colleagues. The more I get to know the songs, though, the more I'm convinced that he and Gershwin are in a class by themselves.

Here's a 1950s Arlen song, "I Never Has Seen Snow," from a criminally obscure Broadway show called House of Flowers that he co-wrote with a young Truman Capote. (This is from a Boston Pops telecast; even if you're not a Vanessa Williams fan, Martha Babcock's cello solo makes it all worthwhile.)

My favorite Arlen songs are the blues- and gospel-flavored numbers he primarily produced with lyricists Ted Koehler and Johnny Mercer. Arlen and Mercer penned a drawerful of gems for a World War II cinematic revue called Star-Spangled Rhythm—the only one to achieve standard status was "That Old Black Magic" (choreographed for the film by George Balanchine; Hollywood used to be a classy place), but some more military-themed songs are priceless, including the brilliant "I'm Doing It For Defense" and the deliciously-titled "He Loved Me Till the All Clear Came." Here's a clip from the movie: sit through 30 seconds of clumsy framing story featuring a Preston Sturges cameo, and you'll be rewarded with Dick Powell and Mary Martin easing their way through "Hit the Road to Dreamland." Those singing waiters? That's the one-and-only Golden Gate Quartet, one of the greatest gospel groups of all time.

Arlen and Koehler achieved immortality with "Stormy Weather," one of dozens of songs they wrote throughout the 30s for such revues as the Cotton Club Parade and Earl Carroll's Vanities. "When the Sun Comes Out" dates from 1940, and it's a beauty. The late, great Barbara McNair just plain sings the hell out of it.

Arlen is a composer I didn't really appreciate until I started accompanying musical theater students. I think you have to physically get your hands on the music before you discover how creative and audacious he is—he's constantly toying with odd phrase lengths, tricky polyrhythmic syncopations, and slippery harmonies that you don't notice as a listener because his feel for the overall style is so suave. That might be why, even though so much of his musical vocabulary is immediately recognizable, he never had as high a profile as some of his more publicly celebrated colleagues. The more I get to know the songs, though, the more I'm convinced that he and Gershwin are in a class by themselves.

May 11, 2007

Careless Talk

Quotes for the day:

Munger also spoke of bright people with streaks of "nuttiness". He gave Mozart as an example. Mozart was a brilliant composer but did nutty things like spend all of his money.That's Charles T. Munger, Chairman of Wesco Financial, as quoted in a report on Wesco's annual shareholder meeting. Munger sounds like he knows from whence he speaks: "Irish Alzheimer's"? I also love his take on global warming: "If Florida is flooded because it is a low elevation, people will have time to move."

Last Tuesday, Garvey was asked to move for the second time this season and got into an exchange with police. In a report of the incident, police said Garvey became heated and "left the area holding his permit, which he believes gives him the right to disturb citizens' peace and quiet."Street musician Jack Garvey, a longtime fixture of downtown Salem, Massachusetts, has been running into trouble with some persnickety condo owners, in spite of his license from the city. The cops got it wrong: you don't need a permit to disturb citizens' peace and quiet—musicians are born with that right. Get used to it.

Her favorite flute composers include Sergei Prokofiev and Dimitri Shostakovich. Her least favorite is modern American composer John Adams.Charleston Symphony Orchestra flutist Regina Helcher accidentally lets slip the way most composers really learn orchestration. Shhhhh!

"I sometimes wish he’d date a flute player just so he’d find out how hard his music is to play," Helcher said.

May 10, 2007

Story of the day, as of 9:20 AM

And they weren't even playing Rite of Spring. Maybe disgruntled Fiedler supporters aren't as docile as they look.

Via Geoff Edgers, who has a picture.

Via Geoff Edgers, who has a picture.

The bustle in a house

I'll be the first to admit that a lot of what gets posted here is only tangentially related to classical music. But, then again, there's a lot of things going on in the world that only seem tangential. Here's an example: subprime mortgages.

Subprime lenders offer mortgages to borrowers with poor credit, typically financing the risk with higher interest rates, penalties for early repayment, and such practices as balloon payments (at the end of a fixed period, the balance of the loan has to be repaid or refinanced). The subprime market has been in trouble lately, with a host of companies going bankrupt in the wake of a rash of foreclosures on adjustable-rate mortgages too freely given out during the housing boom a few years back.

Yesterday, Toll Brothers, the country's largest builder of luxury homes, announced that it would not meet earnings expectations this year. You might wonder why a luxury home builder, whose clients presumably have good credit, would be affected by the subprime implosion. It turns out that the crisis has rippled throughout the entire mortgage industry, with lenders tightening up credit and income restrictions across the board, making it harder for anybody to buy. There's also a domino effect: most people buying luxury homes are upgrading, which means there has to be a middle-class buyer for their previous home, which means that home needs a buyer, and so on down to the base of the pyramid. If first-time home buyers can't get into the market, the owners already in the market can't move up.

Now, if you're wondering where you've seen the Toll Brothers name (and their ubiquitously trademarked America's Luxury Home Builder™ slogan) before, they're the company that took over as lead corporate sponsor of the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts in 2005. The initial agreement only guaranteed support through 2009, however; think the mortgage market will recover by then? Or will Peter Gelb have to start passing the hat like Joe Volpe did after Texaco bailed?

In the grand scheme of things, this is just a blip, and you could certainly make the case that the future of the Met broadcasts is on satellite radio and the Web anyway. But it's a reminder that, no matter how far away an issue may seem from the everyday work of music-making, there's often a more direct connection than there first seems.

Subprime lenders offer mortgages to borrowers with poor credit, typically financing the risk with higher interest rates, penalties for early repayment, and such practices as balloon payments (at the end of a fixed period, the balance of the loan has to be repaid or refinanced). The subprime market has been in trouble lately, with a host of companies going bankrupt in the wake of a rash of foreclosures on adjustable-rate mortgages too freely given out during the housing boom a few years back.

Yesterday, Toll Brothers, the country's largest builder of luxury homes, announced that it would not meet earnings expectations this year. You might wonder why a luxury home builder, whose clients presumably have good credit, would be affected by the subprime implosion. It turns out that the crisis has rippled throughout the entire mortgage industry, with lenders tightening up credit and income restrictions across the board, making it harder for anybody to buy. There's also a domino effect: most people buying luxury homes are upgrading, which means there has to be a middle-class buyer for their previous home, which means that home needs a buyer, and so on down to the base of the pyramid. If first-time home buyers can't get into the market, the owners already in the market can't move up.

Now, if you're wondering where you've seen the Toll Brothers name (and their ubiquitously trademarked America's Luxury Home Builder™ slogan) before, they're the company that took over as lead corporate sponsor of the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts in 2005. The initial agreement only guaranteed support through 2009, however; think the mortgage market will recover by then? Or will Peter Gelb have to start passing the hat like Joe Volpe did after Texaco bailed?

In the grand scheme of things, this is just a blip, and you could certainly make the case that the future of the Met broadcasts is on satellite radio and the Web anyway. But it's a reminder that, no matter how far away an issue may seem from the everyday work of music-making, there's often a more direct connection than there first seems.

May 09, 2007

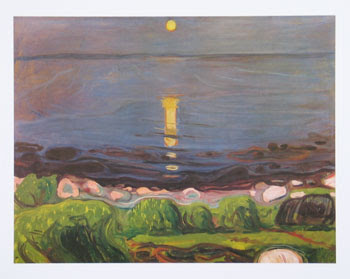

Smiles of a Summer Night

Probably as a result of seeing one too many late night broadcasts of The Train as an impressionable pre-teen, my attention is always diverted by the intersection of Nazi-looted art and famous composers (as you may have noticed). Well, the gilt Art Nouveau rotary hotline here at Soho the Dog HQ lit up this morning with the news that the Austrian government had returned Edvard Munch's "Summer Night at the Beach" (seen above) to Marina Fistoulari-Mahler, Alma and Gustav Mahler's granddaughter, and Alma's sole heir (that must be a fun attic full of birthday cards and old party invitations). The decision was made by the government last November, but the actual transfer took place this week.

Another composer connection: the painting was a gift to Alma from her second husband, Walter Gropius, upon the birth of their daughter Manon—the "angel" whose death inspired Alban Berg's Violin Concerto. In her autobiography, Alma wrote: “No painting has ever touched me in the way this one has."

I Put a Spell on You

Reviewing the Radius Ensemble.

Boston Globe, May 9, 2007.

Cut for space was mention of my favorite movement of Silenzio, the fourth one: whispery notes hammered directly on the strings’ fingerboards with muted accordion clusters. Accordion with strings is such a great combination. (The players for that one were Biliana Voutchkova on violin, sympathetically joined by cellist Agnieszka Dziubak and Cory Pesaturo, playing the bayan part on a Western piano accordion with a deft hand, particularly with the instrument’s finicky delicate registers.)

Boston Globe, May 9, 2007.

Cut for space was mention of my favorite movement of Silenzio, the fourth one: whispery notes hammered directly on the strings’ fingerboards with muted accordion clusters. Accordion with strings is such a great combination. (The players for that one were Biliana Voutchkova on violin, sympathetically joined by cellist Agnieszka Dziubak and Cory Pesaturo, playing the bayan part on a Western piano accordion with a deft hand, particularly with the instrument’s finicky delicate registers.)

Labels:

Globe Articles

May 08, 2007

The lifeblood of democracy

Did you know that ASCAP has a political action committee? (If you're unfamiliar with American politics, PACs are any private group organized to spend money in order to influence elections—most are affiliated with an interest group, corporation, or union.) The ASCAP Legislative Fund for the Arts, to call it by its official title, isn't nearly on par with the big PACs, but they still dished out $157,950 to assorted candidates in the last election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The winners in the House of Representatives:

$5,000 (maximum permitted under law)Howard Berman (D-CA) $4,500John Conyers, Jr. (D-MI) $4,000Steve Chabot (R-OH) Howard Coble (R-NC) Edward Markey, Jr. (D-MA)

In the Senate:

$4,000Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) Edward Kennedy (D-MA) $3,500Kent Conrad (D-ND) $3,000Jon Kyl (R-AZ) $2,500Orrin Hatch (R-UT) Claire McCaskill (D-MO) Jon Tester (D-MT)

(See the whole list here.) It's about 2-1 in favor of Democrats, although ASCAP hedges its bets by favoring Republicans on the soft money side, if the last few available cycles are any indication. (Interestingly, BMI, which has a smaller PAC of its own, favors the GOP for both candidates and soft money.)

I was looking into this in the wake of the whole Internet radio royalty mess, wondering if ASCAP had taken a stand one way or another—although, given that a federal court just shot down an ASCAP assertion that a download of a song is a "performance" for royalty purposes, I would guess that they're not on the side of the little guys. Still, not a word on the subject is to be found on ASCAP's website. (Interestingly, no mention of their PAC, either—the one result via a search seems to have been removed from the actual page.) Here's an indication, though: Reps. Jay Inslee (who got $1,000 from the RIAA last year—you bite that hand that feeds you!) and Don Manzullo have introduced H.R. 2060, which, if enacted, would overturn the Copyright Royalty Board's decision; As of this morning, the bill had attracted 51 co-sponsors—of which only four received ASCAP money (and none of whom got anything from BMI). I don't think ASCAP and BMI are actively working against the bill—I don't think they have to. They've been supporting candidates who already are inclined to back up SoundExchange. I'll predict that they'll remain eerily quiet about this whole thing.

I know that composers of what ASCAP somewhat euphemistically calls "Concert Music" make up a comparatively small part of their membership, but if they and BMI were really serious about supporting all their composers, artists, and publishers, they'd be using some of their clout to make sure that the Internet, the best distribution channel to happen to new and avant-garde music in a hundred years, isn't scorched into an arid wasteland of major-label pap by industry organizations who will go after anyone broadcasting your music whether you want them to or not. It's probably asking too much, but when ASCAP president Marilyn Bergman (full disclosure: I rather like "The Way We Were") tells us:

By the way, the most reliable classical supporter of ASCAP's PAC? Philip Glass.

$5,000 (maximum permitted under law)

In the Senate:

$4,000

(See the whole list here.) It's about 2-1 in favor of Democrats, although ASCAP hedges its bets by favoring Republicans on the soft money side, if the last few available cycles are any indication. (Interestingly, BMI, which has a smaller PAC of its own, favors the GOP for both candidates and soft money.)

I was looking into this in the wake of the whole Internet radio royalty mess, wondering if ASCAP had taken a stand one way or another—although, given that a federal court just shot down an ASCAP assertion that a download of a song is a "performance" for royalty purposes, I would guess that they're not on the side of the little guys. Still, not a word on the subject is to be found on ASCAP's website. (Interestingly, no mention of their PAC, either—the one result via a search seems to have been removed from the actual page.) Here's an indication, though: Reps. Jay Inslee (who got $1,000 from the RIAA last year—you bite that hand that feeds you!) and Don Manzullo have introduced H.R. 2060, which, if enacted, would overturn the Copyright Royalty Board's decision; As of this morning, the bill had attracted 51 co-sponsors—of which only four received ASCAP money (and none of whom got anything from BMI). I don't think ASCAP and BMI are actively working against the bill—I don't think they have to. They've been supporting candidates who already are inclined to back up SoundExchange. I'll predict that they'll remain eerily quiet about this whole thing.

I know that composers of what ASCAP somewhat euphemistically calls "Concert Music" make up a comparatively small part of their membership, but if they and BMI were really serious about supporting all their composers, artists, and publishers, they'd be using some of their clout to make sure that the Internet, the best distribution channel to happen to new and avant-garde music in a hundred years, isn't scorched into an arid wasteland of major-label pap by industry organizations who will go after anyone broadcasting your music whether you want them to or not. It's probably asking too much, but when ASCAP president Marilyn Bergman (full disclosure: I rather like "The Way We Were") tells us:

[W]e have to be wary of the well-spoken hucksters out there trying to trick us out of the most fundamental right we have, the right to control the uses of our own work, and the right to be fairly paid for those usesI hope she's making room in her organization for those of us who count the RIAA as one of those hucksters.

By the way, the most reliable classical supporter of ASCAP's PAC? Philip Glass.

May 07, 2007

Hang It Up

Peter Gelb ran another idea up the flagpole last night, with the first "Art for Opera" auction, which raised nearly two million dollars for the Metropolitan Opera. After "cocktails and dinner amidst Allen Moyer's set for the new staging of Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice," which might be the most amusing sentence you'll see today—what, every time you turn around, somebody takes your plate away?—guests (who already paid between $750 and $1250 to get in and eat) bid on operatically-themed works by various contemporary artists, including an eight-by-six-foot photorealistic Chuck Close tapestry portrait of Renée Fleming that would probably scare the hell out of me if I was walking around the house at night. (Take a look at some items here.) Critic-at-large Moe's favorite—this William Wegman homage to Hansel and Gretel—went for $50,000. That's a lot of liver treats.

World Wide Web

Reviewing Boston Musica Viva.

Boston Globe, May 7, 2007.

Boston Globe, May 7, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

May 04, 2007

Three-Chord Monte

The other day I came across this excellent, concise history of the Chicago-area punk band Screeching Weasel on the terrifically-named blog Can You See the Sunset From the Southside? This was a straight nostalgia trip for me: the suburb where Weasel and Jughead got their start was where I grew up. I met them a couple of times in the early days, the most memorable being when my friend Nick talked them into visiting the Maine East High School cable access TV studio for an interview. (I think I was technical director for that one.) I had a copy of their self-titled first album; "Murder In the Brady House" was a particular favorite. Nick also turned me on to the Dead Kennedys, and then Jack Miller (who's put in occasional cameos on this blog) dubbed off some Sex Pistols rarities for me, and I was hooked.

I still go through occasional punk phases, and about every eighth piece I start writing, I find myself thinking "now, this one should be just like a punk rock song" (after which it usually comes out nothing like a punk rock song). I did some summer teaching last year, and the overwhelming majority of my students (music ed majors) were horrified to find out that I enjoyed this stuff; on the one hand, I was puzzled, since I've always thought of punk as a late revival of early 1950s rock-and-roll (Eddie Cochran? Punk rocker), and who doesn't like that stuff? On the other hand, I was sardonically pleased that it still had the power to charm, as it were.

Unlike our classmate and one-time Screeching Weasel bassist Johnny Personality, I was always a closet fan—I never had the requisite courage for a mohawk or multiple piercings—but regardless of genre, I'm still attracted to music that gives off a whiff of the style: tight, utilitarian bursts of energy that make no effort to soften any rough edges. More importantly, it's the attitude of being exactly what it is and making no apologies for it. Maybe that's why I go from Arthur Fiedler to Ben Weasel without any cognitive dissonance. I think that's a big difference between the way musicians and non-musicians listen to music: if you're able to empathize with the creator, you start to see that all this stuff, no matter how disparate, is coming from the same place. Ives? Mahler? Beethoven? Josquin? Punks.

Post title stolen from another Chicago punk band, Pegboy.

I still go through occasional punk phases, and about every eighth piece I start writing, I find myself thinking "now, this one should be just like a punk rock song" (after which it usually comes out nothing like a punk rock song). I did some summer teaching last year, and the overwhelming majority of my students (music ed majors) were horrified to find out that I enjoyed this stuff; on the one hand, I was puzzled, since I've always thought of punk as a late revival of early 1950s rock-and-roll (Eddie Cochran? Punk rocker), and who doesn't like that stuff? On the other hand, I was sardonically pleased that it still had the power to charm, as it were.

Unlike our classmate and one-time Screeching Weasel bassist Johnny Personality, I was always a closet fan—I never had the requisite courage for a mohawk or multiple piercings—but regardless of genre, I'm still attracted to music that gives off a whiff of the style: tight, utilitarian bursts of energy that make no effort to soften any rough edges. More importantly, it's the attitude of being exactly what it is and making no apologies for it. Maybe that's why I go from Arthur Fiedler to Ben Weasel without any cognitive dissonance. I think that's a big difference between the way musicians and non-musicians listen to music: if you're able to empathize with the creator, you start to see that all this stuff, no matter how disparate, is coming from the same place. Ives? Mahler? Beethoven? Josquin? Punks.

Post title stolen from another Chicago punk band, Pegboy.

May 03, 2007

The Dangling Conversation

Yesterday, Geoff Edgers and Scooter at Unpleasant! were grokking on Arthur Fiedler's "Saturday Night Fiedler" disco album with the Boston Pops, which sent me to the turntable with my own favorite, "Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Play the Music of Paul Simon."

Boston Pops/Fiedler—"Feelin' Groovy" (MP3, 2.2 Mb)

Yes, it's one of the world's leading orchestras playing "Feelin' Groovy." How can you resist? Their version of "Mrs. Robinson" is not bad, either. (All the arrangements on the album are by the legendary Richard Hayman, who would be a hero around these parts just for being a member of Borah Minevitch's Harmonica Rascals. But I digress.)

As a kid, these sorts of arrangements were actually my favorite portions of "Evening at Pops," which perhaps demonstrates both how old and uncool I am. But the willful cognitive dissonance between the source material and the end result always tickled my fancy. Taking a modest little pop song and pumping it up with the grandeur of an orchestra was a great way to get seduced by that sound: the full impact of symphonic glory laced with just enough good-natured absurdity to dissolve any encrusted sanctity.

Whatever happened to those sorts of arrangements? Well, pop music itself gradually expanded to symphonic proportions. In a way, a song like "Born to Run," with its melodramatic orchestration and ambition, is already its own Pops arrangement; the fun of hearing three-chord progressions inflated to Wagnerian scale became redundant.

To me, most symphonic pop music just sounds artificially big. (The only guy I ever thought got it right was Brian Wilson, who used the orchestra as an expanded palette—the exotic instrumental colors function as extensions or reimaginations of the sorts of sounds you'd find in a typical pop combo.) But Pops arrangements, because of the context and the presentation, always existed in a kind of playful limbo, free to pick and choose from both sides of the ledger. Sometimes the results were incongruously grandiose. Sometimes they were just goofy. But often, they were grand and goofy, a terrific combination that's all too rare in any genre. It's the sort of charge you get from an over-the-top yet sincerely skillful Hollywood production number, or a particularly elaborate run of physical comedy, or the highbrow/lowbrow alternating current of the best visual pop art.

If I ever was put in charge of the Pops, the first thing I'd do is commission a whole bunch of those young-gun postminimalist pop-influenced composers out there to do arrangements of their favorite songs—not for the orchestra to back up said acts, but as the sort of stand-alone pieces that Fiedler used to do. (The Pops have commissioned an original piece from Nico Muhly—go on, hit him up for another!) Think of it as cleaning up a fun little playground in a corner of the cultural landscape that's fallen into disuse. Is it for everybody? Nah—lots of people outgrow jungle gyms. But, then again, aren't the ones who don't more fun to hang out with?

Boston Pops/Fiedler—"Feelin' Groovy" (MP3, 2.2 Mb)

Yes, it's one of the world's leading orchestras playing "Feelin' Groovy." How can you resist? Their version of "Mrs. Robinson" is not bad, either. (All the arrangements on the album are by the legendary Richard Hayman, who would be a hero around these parts just for being a member of Borah Minevitch's Harmonica Rascals. But I digress.)

As a kid, these sorts of arrangements were actually my favorite portions of "Evening at Pops," which perhaps demonstrates both how old and uncool I am. But the willful cognitive dissonance between the source material and the end result always tickled my fancy. Taking a modest little pop song and pumping it up with the grandeur of an orchestra was a great way to get seduced by that sound: the full impact of symphonic glory laced with just enough good-natured absurdity to dissolve any encrusted sanctity.

Whatever happened to those sorts of arrangements? Well, pop music itself gradually expanded to symphonic proportions. In a way, a song like "Born to Run," with its melodramatic orchestration and ambition, is already its own Pops arrangement; the fun of hearing three-chord progressions inflated to Wagnerian scale became redundant.

To me, most symphonic pop music just sounds artificially big. (The only guy I ever thought got it right was Brian Wilson, who used the orchestra as an expanded palette—the exotic instrumental colors function as extensions or reimaginations of the sorts of sounds you'd find in a typical pop combo.) But Pops arrangements, because of the context and the presentation, always existed in a kind of playful limbo, free to pick and choose from both sides of the ledger. Sometimes the results were incongruously grandiose. Sometimes they were just goofy. But often, they were grand and goofy, a terrific combination that's all too rare in any genre. It's the sort of charge you get from an over-the-top yet sincerely skillful Hollywood production number, or a particularly elaborate run of physical comedy, or the highbrow/lowbrow alternating current of the best visual pop art.

If I ever was put in charge of the Pops, the first thing I'd do is commission a whole bunch of those young-gun postminimalist pop-influenced composers out there to do arrangements of their favorite songs—not for the orchestra to back up said acts, but as the sort of stand-alone pieces that Fiedler used to do. (The Pops have commissioned an original piece from Nico Muhly—go on, hit him up for another!) Think of it as cleaning up a fun little playground in a corner of the cultural landscape that's fallen into disuse. Is it for everybody? Nah—lots of people outgrow jungle gyms. But, then again, aren't the ones who don't more fun to hang out with?

May 02, 2007

Beethoven needs curtains

MY EXCELLENT FRIEND,—A letter to Beethoven's longtime Viennese acquaintance Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz, on the eve of the mammoth December 22, 1808 benefit concert at the Theater an der Wien which saw the premieres of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy. (The piece in question here is the concert aria Ah! perfido.)

All would go well now if we had only a curtain, without it the Aria will be a failure. I only heard this to-day from S., and it vexes me much: a curtain of any kind will do, even a bed-curtain, or merely a kind of gauze screen, which could be instantly removed. There must be something; for the Aria is in the dramatic style, and better adapted for the stage than for effect in a concert-room. Without a curtain, or something of the sort, the Aria will be devoid of all meaning, and ruined! ruined! ruined!! Devil take it all! The Court will probably be present. Baron Schweitzer requested me earnestly to make the application myself. Archduke Carl granted me an audience and promised to come. The Empress neither promised nor refused.

A hanging curtain!!!! or the Aria and I will both be hanged to-morrow. Farewell! I embrace you as cordially on this new year as in the old one. With or without a curtain! Your

BEETHOVEN.

May 01, 2007

They Can't Take That Away From Me

Happy Loyalty Day! No kidding. According to the government:

I should probably include something musical, right? Go here and listen to the "Eight-Hour Song." (Part of another excellent survey.)

All citizens can express their loyalty to the United States by flying the flag, participating in our democracy, and learning more about our country's grand story of courage and simple dream of dignity.You want to learn more about simple dreams of dignity? Start here. (I suppose some people might consider it disloyal to point out the cynical coincidence of May Day and "Loyalty Day." Oh, well. Besides, they didn't say which flag.)

I should probably include something musical, right? Go here and listen to the "Eight-Hour Song." (Part of another excellent survey.)

Din and tonic

Reviewing Evgeny Kissin.

Boston Globe, May 1, 2007.

Mention of the sixth of the Brahms op. 118 pieces, the E-flat minor "Intermezzo," was cut for space (and accidentally conflated with the fifth, which was not particularly slow): Kissin took it at a remarkably slow and improvisatory tempo, fascinatingly calling up echoes and portends of late Liszt, Debussy, and early Schoenberg—and making the force of the middle section explosive. It was his most experimental playing of the night. With that command over color and texture, Kissin could actually be one of the all-time great interpreters of the avant-garde repertoire if he wanted—imagine if he ever tackled the Ligeti Etudes or the Barraqué Sonata.

And the coughing? Seriously: I felt like I was in a foley session for The Magic Mountain movie.

Update (5/2): A reader asked about the Horowitz "Carmen Variations" that Kissin played as an encore. Horowitz tinkered with the piece throughout his career; Kissin's performance sounded like either the 1968 Carnegie Hall version or the 1978 White House version (which are fairly similar). The first recorded version (from 1927) was shorter; a version recorded (but never released) in the 1950's is the most elaborate. You can compare transcriptions of the various versions here.

Boston Globe, May 1, 2007.

Mention of the sixth of the Brahms op. 118 pieces, the E-flat minor "Intermezzo," was cut for space (and accidentally conflated with the fifth, which was not particularly slow): Kissin took it at a remarkably slow and improvisatory tempo, fascinatingly calling up echoes and portends of late Liszt, Debussy, and early Schoenberg—and making the force of the middle section explosive. It was his most experimental playing of the night. With that command over color and texture, Kissin could actually be one of the all-time great interpreters of the avant-garde repertoire if he wanted—imagine if he ever tackled the Ligeti Etudes or the Barraqué Sonata.

And the coughing? Seriously: I felt like I was in a foley session for The Magic Mountain movie.