(An indistinct landscape. A long line of people waiting to pass through a simple, nondescript checkpoint. In the middle of the line, James Brown. Behind him, Gerald Ford. After a while, Ford tries to make conversation.)

GF: My stepfather was a magnificent person, and my mother equally wonderful. So I couldn't have written a better prescription for a superb family upbringing.

JB: Where I grew up there was no way out, no avenue of escape, so you had to make a way. Mine was to create James Brown.

(Pause.)

GF: I am proud of America, and I am proud to be an American. Life will be a little better here for my children than for me. I believe this not because I am told to believe it, but because life has been better for me than it was for my father and my mother.

(JB shrugs.)

JB: Any time an Afro-American kid, 9 or 10 years old, can get up and say "Mama, I think I'm gonna study hard because I want to be president," and have a shot at being president, then we've got America. Other than that, we've got a name and we're trying to find out what it means.

GF (defensively): The words I remember best were spoken by Dwight D. Eisenhower. "America is not good because it is great," the President said. "America is great because it is good."

(A long pause. JB looks up and down the line of people.)

JB: Killing's out and school's in and we're in bad shape.

(GF nods.)

GF: This is an hour of history that troubles our minds and hurts our hearts.

JB: The real answer to race problems in this country is education. Not burning and killing. Be ready. Be qualified. Own something. Be somebody. That's Black Power.

GF: "Black is beautiful" was a motto of genius which uplifted us far above its intention. Once Americans had thought about it and perceived its truth, we began to realize that so are brown, white, red, and yellow beautiful.

JB: I think what I came through is great, but my son can take it to another level, not having to fight racism. His mother's a Norwegian and I'm mixed up four or five times, so he can face the world.

(Another long pause. GF looks tired.)

GF: Sometimes we stumble in the dark, uncertain of the best course for ourselves and the nation we love.

(JB turns around.)

JB: It doesn't matter how you travel it, it's the same road. It doesn't get any easier when you get bigger, it gets harder. And it will kill you if you let it.

GF: We cannot stand still or slip backwards. We must go forward now together.

(JB turns around again, nodding and smiling.)

JB: Die on your feet, don't live on your knees.

December 28, 2006

December 22, 2006

Bark us all bow-wows of folly

Just a quick programming note: because of festive-type obligations, Soho the Dog will be officially on hiatus next week. That doesn't mean there might not be an unofficial post or two if the spirit moves me, but I'm not making any promises.

In the meantime, I should probably start practicing those Balbastre Noëls for Christmas. When's Christmas again? Oh, yeah—"The Twenty-Fifth of December" (as performed by the Middle Georgia Four in 1943).

Safe travels to anyone braving our crumbling transportation infrastructure. Happy holidays!

December 21, 2006

"Her name was Priscilla"

Cellist Charlotte Moorman describes the circumstances of her meeting Nam June Paik. Supporting characters include Karlheinz Stockhausen, Allen Ginsburg, James Tenney (in fur ears and G-string), the NYPD, and a chimp.

Filmed in 1980 by Fred Stern (link warning: auto-loading Zarathustra music), who has also been posting his avant-garde video work.

Filmed in 1980 by Fred Stern (link warning: auto-loading Zarathustra music), who has also been posting his avant-garde video work.

He's making a list; he's checking it twice

I was humming Christmas carols to myself last night, and I noticed that an awful lot of them start on the fifth scale degree. "Away in a Manger," "Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming," "Hark! the Herald Angels Sing," "Il est né," "Silent Night"—lots of them begin with sol. And, being me, I wondered: what kind of a data set would I need to see if this is a statistically significant variance? (Yeah, I'm that much fun at parties.)

I was humming Christmas carols to myself last night, and I noticed that an awful lot of them start on the fifth scale degree. "Away in a Manger," "Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming," "Hark! the Herald Angels Sing," "Il est né," "Silent Night"—lots of them begin with sol. And, being me, I wondered: what kind of a data set would I need to see if this is a statistically significant variance? (Yeah, I'm that much fun at parties.)Because of my job, I always have lots of Presbyterian hymnals lying around, so I used one of those. I tallied all the initial melodic scale degrees for the Christmas hymns, and then did the same for the rest of the book. Note that I tallied hymns, not tunes; if a tune was used more than once, it got counted more than once. (I skipped the service music.) A few of the tunes (less than 10) were chant-based, which didn't always make it readily apparent what tonic was; I made judgment calls based on the prevailing harmony. Here's what I got:

Christmas hymns (39):The positions of the 1st and 5th scale degrees are pretty much reversed. In fact, if you take the non-Christmas hymns as representing the expected distribution of initial pitch level, and then run a Pearson chi-square test on the Christmas hymns, you get a chi-square value of 6.385 (I hope I did that right; any mathematically-inclined readers out there should feel free to check my work); convert that to a probability (I used Richard Lowry's online calculator) and you get 0.0411—that is, there's about a 4% chance of finding yourself as far out on the tail of the distribution as the Christmas hymns are.

Scale degree 1: 13 (33.3%)

Scale degree 3: 7 (18.0%)

Scale degree 5: 19 (48.7%)

Non-Christmas hymns (518):

Scale degree 1: 233 (45.0%)

Scale degree 3: 84 (16.2%)

Scale degree 5: 196 (37.8%)

Other: 5 (1%)

Weird. Why would Christmas songs be more likely to start on sol than do? Maybe it has to do with the season of Advent, the four weeks before Christmas in the Christian calendar. It's the only part of the church year that's specifically devoted to waiting (Lent, the period leading up to Easter, is much more about penance and reflection). By the time you get to Christmas itself, you've been spiritually standing around for the better part of a month. Slow carols tend to start on sol and then take their time getting to tonic, perhaps a musical reminder of the joys of expectation; fast ones jump in with a solid V-I cadence, a harmonic reassurace that, yes, you've made it, the day is finally here.

Or maybe it's just a coincidence. Something to listen for over the weekend, though.

Update (12/22): Critic-at-large Moe pointed out to me that my math was only half right—I did the chi-square test on the percentages, which would be the equivalent of a 100-Christmas-hymn sample. If you use the actual 39-hymn sample, the chi-square is 2.63, which gives you a probability of 0.2685—about a 27% chance, in other words. To my taste, that's still too far out on the curve for a random variance.

December 20, 2006

I didn't come here to be consulted

Lord knows I try to be funny. I love coming up with absolutely absurd notions about music for your amusement. But OboeInsight reminds me that, try as I may, I just can't compete with reality.

Canadian arts consultant Elaine Calder, hired by the Oregon Symphony to evaluate its weaknesses, has suggested that one problem is that the orchestra plays too much classical music.She also suggested that zoos have too many animals and that sushi restaurants serve too much fish. It's a symphony orchestra, you moron. What do you want them to play? Oh, right.

[Calder] points out that when the Edmonton orchestra played with Christian soft-rock singer Michael W. Smith, $250,000 worth of tickets were sold, mostly to symphony newcomers.Oh, dear God. I'm all for pops concerts that boost the bottom line, but not pops concerts that are straight-up religious pandering. (How about some klezmer concerts and visits to the temple? An oud soloist and a trip to the mosque? Nah—it's not like those people will ever assimilate. Besides, there aren't enough of them to make pandering financially worthwhile!) If I were a patron of the Oregon Symphony, I'd be downsizing my donations by the exact amount they're paying this blowhard.

She also advocates performing in other locations, like churches, according to The Oregonian.

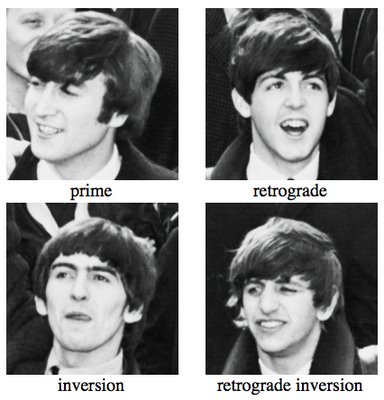

Variations (2)

One wet morning, when she was playing the hotel piano, and he listening, thinking to have her to himself, there came a young German violinist—pale, and with a brown, thin-waisted coat, longish hair, and little whiskers—rather a beast, in fact. Soon, of course, this young beast was asking her to accompany him—as if anyone wanted to hear him play his disgusting violin! Every word and smile that she gave him hurt so, seeing how much more interesting than himself this foreigner was! And his heart grew heavier and heavier, and he thought: If she likes him I ought not to mind—only, I DO mind! How can I help minding? It was hateful to see her smiling, and the young beast bending down to her. And they were talking German, so that he could not tell what they were saying, which made it more unbearable. He had not known there could be such torture.—John Galsworthy, The Dark Flower

(It wasn't like the time I lost my boy—the time my boy played the piano with that girl Reina in a little New England farmhouse near Bennington, and I realized at last I wasn't wanted. Guy Lombardo was on the air playing Top Hat and Cheek to Cheek, and she taught him the melodies. The keys falling like leaves and her hands splayed over his as she showed him a black chord. I was a freshman then.)—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Last Tycoon

CHARTERIS. She did what a woman like Julia always does. When I explained personally, she said it was not not my better self that was speaking, and that she knew I still really loved her. When I wrote it to her with brutal explicitness, she read the letter carefully and then sent it back to me with a note to say that she had not had the courage to open it, and that I ought to be ashamed of having written it. (Comes beside Grace, and puts his left hand caressingly round her neck.) You see, dearie, she won't look the situation in the face.

GRACE. (shaking off his hand and turning a little away on the stool). I am afraid, from the light way in which you speak of it, you did not sound the right chord.

CHARTERIS. My dear, when you are doing what a woman calls breaking her heart, you may sound the very prettiest chords you can find on the piano; but to her ears it is just like this—(Sits down on the bass end of the keyboard. Grace puts her fingers in her ears.)—George Bernard Shaw, The Philanderer

December 19, 2006

Cemetery Blues

Bring me the head of Georges Bizet! The bronze bust of the composer, best known for his operas Le docteur Miracle, Don Procopio, and Numa (he was also known to dabble in Spanish themes now and again), has been stolen from his grave in the famed Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Investigators might want to check that now remounted Berlin production of Idomeneo (which, yesterday, I heard our local news radio station pronounce as Indomínio, with the accent on the third syllable, making it sound like a Phil Collins song). They were down a few heads as of last week—maybe they got desparate.

In terms of borrowing from Bizet, though, it doesn't compare with the Horowitz transcription. (The Bizet starts at the 3:36 mark; you'll have to sit through Schumann's Träumerei first, which isn't such a bad thing.)

That's from his 1968 Carnegie Hall recital. Wondering what all those notes were? You can compare various transcriptions of all the successive versions of Horowitz's Carmen Variations here (as well as other Horowitz arrangements and compositions, including the early "Danse Excentrique," which remains one of my more prized 78s).

Also via YouTube, here's a couple of wonderful silent home movies of Horowitz playing at parties in the 1920's. If your primary image of Horowitz is as a kindly old man being bossed around by Toscanini's daughter, it's fun to see him at his most rakishly sly. I wonder what he's playing in the first clip—he seems to be having a great time hamming it up.

Incidentally, the Horowitzes are unfortunately also no strangers to grave robbers. (And you thought I couldn't bring this meandering post full circle.)

"We're dealing with a group theft carried out over a short period of time," said an unnamed source quoted in The Independent. "And there is without doubt a collector behind it. The pieces are almost never catalogued, and so it would be very easy to sell them on the black market."And only five shopping days left until Christmas! I need to update my list.

Investigators might want to check that now remounted Berlin production of Idomeneo (which, yesterday, I heard our local news radio station pronounce as Indomínio, with the accent on the third syllable, making it sound like a Phil Collins song). They were down a few heads as of last week—maybe they got desparate.

In terms of borrowing from Bizet, though, it doesn't compare with the Horowitz transcription. (The Bizet starts at the 3:36 mark; you'll have to sit through Schumann's Träumerei first, which isn't such a bad thing.)

That's from his 1968 Carnegie Hall recital. Wondering what all those notes were? You can compare various transcriptions of all the successive versions of Horowitz's Carmen Variations here (as well as other Horowitz arrangements and compositions, including the early "Danse Excentrique," which remains one of my more prized 78s).

Also via YouTube, here's a couple of wonderful silent home movies of Horowitz playing at parties in the 1920's. If your primary image of Horowitz is as a kindly old man being bossed around by Toscanini's daughter, it's fun to see him at his most rakishly sly. I wonder what he's playing in the first clip—he seems to be having a great time hamming it up.

Incidentally, the Horowitzes are unfortunately also no strangers to grave robbers. (And you thought I couldn't bring this meandering post full circle.)

December 18, 2006

"Oh, take your next vacation in a brand new Frigidaire"

If you follow these things, you probably know by now that last week, Bank of America announced that it will no longer sponsor the Celebrity Series, one of the more venerable and reliable classical-music (and dance) concert promoters here in Boston. The Celebrity Series was founded in 1938 by Aaron Richmond (check out the first few seasons here, they're pretty amazing)—since then, it's operated under the auspices of Boston University, the Wang Center for the Performing Arts (soon to be the CitiCenter), and, since 1989, as a non-profit with Bank of Boston and its successors as lead sponsor. Three mergers later, North Carolina-based Bank of America is pulling out.

That's fine—it's their money, they can do with it what they like—but what's with the disingenuous smarm?

Yeah, yeah, I could probably pull skeletons out of any corporate closet I peer into. But come on—do you really expect us to believe that Bank of America is yanking its funding as some form of tough love? This is a numbers game. It should also be another shovelful of cemetery soil on the notion that corporations view arts philanthropy as anything more than tax-deductible advertising.

BoA was contributing $600,000 a year to the Celebrity Series. The Celebrity Series pulls in about 100,000 people a year; that works out to six bucks a person. To compare, they've also given $5 million over the past two years to Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, including underwriting this year's big "Americans in Paris" exhibition; extrapolating out from the only numbers I could find, the "Americans in Paris" show drew about 100,000 people in approximately three months. The back-of-the-envelope math still works out to around six bucks a person ($5 mil/24 months/~30,000 people per month; there's added benefits for BoA in that the exhibition also visited London and New York, but nobody's talking as to how much exactly was spent, and I don't think it would make a huge difference in the calculation).

But figure in the number of people passing through the museum who didn't buy the extra ticket needed for the exhibition, along with the plethora of bus, billboard, and streetlight-banner advertising that the MFA pumped out, all featuring the BoA logo, and that's a lot more corporate exposure for your buck. In other words, the Celebrity Series is getting dumped not because it's less efficient than other arts organizations, but because it's more poorly suited to ancillary advertising benefits. It doesn't have its own building; it doesn't get a lot of "passers-by" to glimpse a corporate logo as they walk through; it isn't big enough (as, for example, the MFA or the BSO) to warrant the kind of civic boosterism exemplified by those ubiquitous streetlamp banners.

BoA talks about changing "priorities," but the driving force behind those priorities isn't artistic excellence or value to the community. It's rather that the priorities are things BoA can permanently and physically slap its name on, the emphasis is on philanthropy that comes with a high-profile billboard for the brand. Why do you think BoA is shifting its performing arts support to free and/or open-air events—and concentrating more and more on museums? (Peruse this already out-of-date list.) Why do you think their competitor CitiGroup spent $34 million to rename the Wang Center? Why do you think (in the for-profit realm) BoA is also spending a ton of money to sponsor NASCAR, as close to a gravitational singularity of corporate branding as you can get?

Again, they're just doing what good corporations do to build their brand. But there's two forces at work here that musicians need to be aware of. As corporations get bigger and bigger, and are frequently operating far away from their own home base, corporate visibility and brand promotion will become the main goal of all non-operational activity; the personal relationships and local civic pride that support smaller, less splashy causes will become more and more abstract until they disappear completely. And if visibility is the key, let's face it: music is not the most visible of art forms. It would appear that the transitory, elusive nature of music has a real-world financial cost, at least in a society where the free market reigns, and philanthropy is just another front in the war for eyeballs. There's a built-in bias towards the visual arts and organizations with a bricks-and-mortar component; mid-level venue-renting classical music organizations like the Celebrity Series, too big to scrape by on government grants and small donations, too small to be attractive to increasingly huge corporations, are left high and dry.

What's to be done? Not much, I'm afraid. There are possible tax structures to try and alleviate this—for example, you could tie deduction rates to geographic diversity for companies operating in multiple states, or a balance between large and small receiving organizations; you could give greater breaks for long-term support, either via year-to-year increases or favors on extended commitments—but they all have significant downsides, and, more importantly, they'd just be used by corporations as an excuse to be less philanthropic overall. You could aggressively enforce anti-trust legislation—ahhh, who am I kidding?

No, the problem here is that corporate philanthropy requires a free-market benefit, and the benefits of classical music are rather poorly perceived by the free market—and those benefits are downright invisible unless the guy who pays the piper can make him wear a sandwich-board as well. Maybe you're you're more sanguine than I am about private philanthropy stepping in to close the gap, but for me, it's this sort of situation that government arts funding was invented for—fixing the holes that the free market leaves behind. Yes, the government is inefficient, and unresponsive, and often downright stupid, but at least there's a veneer of accountability, and at least they're not particularly worried about building their brand (domestically, anyways). Besides, the alternative is like a boyfriend who breaks up with you because you don't have enough pictures of him on your wall, and then tries to tell you it's for your own good.

(The title? From these guys. The rest.)

That's fine—it's their money, they can do with it what they like—but what's with the disingenuous smarm?

[BoA Massachusetts President Robert] Gallery said it makes sense for the 68-year-old Celebrity Series to become more self-sufficient....Thanks for the advice, Polonius. Unfortunately, unlike your company, Bob, the Celebrity Series doesn't have access to providers like, say, customers' Social Security benefits, or $42 million in taxpayer-funded job retention subsidies (not that the last round of corporate welfare kept any of those jobs around), or $650 million in 9/11 Liberty Bonds to build a new office, um, nowhere near Ground Zero.

"These things have a life cycle, and this has been a pretty long run," said Gallery. "We're very proud of that, but every organization we work with, we want them to reach out to as broad a community as they can to develop as their funding base. No institution should be too dependent on one provider."

Yeah, yeah, I could probably pull skeletons out of any corporate closet I peer into. But come on—do you really expect us to believe that Bank of America is yanking its funding as some form of tough love? This is a numbers game. It should also be another shovelful of cemetery soil on the notion that corporations view arts philanthropy as anything more than tax-deductible advertising.

BoA was contributing $600,000 a year to the Celebrity Series. The Celebrity Series pulls in about 100,000 people a year; that works out to six bucks a person. To compare, they've also given $5 million over the past two years to Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, including underwriting this year's big "Americans in Paris" exhibition; extrapolating out from the only numbers I could find, the "Americans in Paris" show drew about 100,000 people in approximately three months. The back-of-the-envelope math still works out to around six bucks a person ($5 mil/24 months/~30,000 people per month; there's added benefits for BoA in that the exhibition also visited London and New York, but nobody's talking as to how much exactly was spent, and I don't think it would make a huge difference in the calculation).

But figure in the number of people passing through the museum who didn't buy the extra ticket needed for the exhibition, along with the plethora of bus, billboard, and streetlight-banner advertising that the MFA pumped out, all featuring the BoA logo, and that's a lot more corporate exposure for your buck. In other words, the Celebrity Series is getting dumped not because it's less efficient than other arts organizations, but because it's more poorly suited to ancillary advertising benefits. It doesn't have its own building; it doesn't get a lot of "passers-by" to glimpse a corporate logo as they walk through; it isn't big enough (as, for example, the MFA or the BSO) to warrant the kind of civic boosterism exemplified by those ubiquitous streetlamp banners.

BoA talks about changing "priorities," but the driving force behind those priorities isn't artistic excellence or value to the community. It's rather that the priorities are things BoA can permanently and physically slap its name on, the emphasis is on philanthropy that comes with a high-profile billboard for the brand. Why do you think BoA is shifting its performing arts support to free and/or open-air events—and concentrating more and more on museums? (Peruse this already out-of-date list.) Why do you think their competitor CitiGroup spent $34 million to rename the Wang Center? Why do you think (in the for-profit realm) BoA is also spending a ton of money to sponsor NASCAR, as close to a gravitational singularity of corporate branding as you can get?

Again, they're just doing what good corporations do to build their brand. But there's two forces at work here that musicians need to be aware of. As corporations get bigger and bigger, and are frequently operating far away from their own home base, corporate visibility and brand promotion will become the main goal of all non-operational activity; the personal relationships and local civic pride that support smaller, less splashy causes will become more and more abstract until they disappear completely. And if visibility is the key, let's face it: music is not the most visible of art forms. It would appear that the transitory, elusive nature of music has a real-world financial cost, at least in a society where the free market reigns, and philanthropy is just another front in the war for eyeballs. There's a built-in bias towards the visual arts and organizations with a bricks-and-mortar component; mid-level venue-renting classical music organizations like the Celebrity Series, too big to scrape by on government grants and small donations, too small to be attractive to increasingly huge corporations, are left high and dry.

What's to be done? Not much, I'm afraid. There are possible tax structures to try and alleviate this—for example, you could tie deduction rates to geographic diversity for companies operating in multiple states, or a balance between large and small receiving organizations; you could give greater breaks for long-term support, either via year-to-year increases or favors on extended commitments—but they all have significant downsides, and, more importantly, they'd just be used by corporations as an excuse to be less philanthropic overall. You could aggressively enforce anti-trust legislation—ahhh, who am I kidding?

No, the problem here is that corporate philanthropy requires a free-market benefit, and the benefits of classical music are rather poorly perceived by the free market—and those benefits are downright invisible unless the guy who pays the piper can make him wear a sandwich-board as well. Maybe you're you're more sanguine than I am about private philanthropy stepping in to close the gap, but for me, it's this sort of situation that government arts funding was invented for—fixing the holes that the free market leaves behind. Yes, the government is inefficient, and unresponsive, and often downright stupid, but at least there's a veneer of accountability, and at least they're not particularly worried about building their brand (domestically, anyways). Besides, the alternative is like a boyfriend who breaks up with you because you don't have enough pictures of him on your wall, and then tries to tell you it's for your own good.

(The title? From these guys. The rest.)

December 17, 2006

This is your brain on drugs

Last week's post on all things edible and ovoid brought forth a slew of creativity from the ether. I recommend you experience the entire comment thread in all it's mouth-watering glory; here are a few of my favorites.

Last week's post on all things edible and ovoid brought forth a slew of creativity from the ether. I recommend you experience the entire comment thread in all it's mouth-watering glory; here are a few of my favorites.From Ben.H of Boring Like a Drill fame:

Eggs Antheil: Place a pistol in clear sight on the kitchen counter. Cook eggs using fifteen pressure cookers, while switching on every fan, electric mixer, garbage disposal, blender, and smoke alarm. When done, throw out the lot and cook another set of eggs in a traditional manner, as your mother used to make. Serve with a toast to Hedy Lamarr. Do not switch off your cellphone.(This one actually got my lovely wife curious enough to want to hear some Antheil.)

From the intensely serene Seth Gordon:

Eggs Cardew: Truffles are for the elitists! I will eat my eggs with a simple accompaniment of fermented beans and fish heads, as Chairman Mao did.Be sure to also check out Seth's updated Eggs Partch recipe, which is a thing of beauty.

Galen Brown leaves us wanting more:

Eggs Cage: Heat up your frying pan. Turn it off. Think about what not eating eggs tastes like.Although, as Mark Meyer cautions, best to avoid cage-free eggs.

Speaking of Cage, Colin Holter whips up an imaginary landscape:

Eggs Champaign-Urbana: Devise an elaborate plan for cooking eggs in a manner that will produce mildly piquant results. (Consider Herbert Brun's ideas on language.) When finished, name your eggs with an adjective followed by a singular common noun.In honor of UIUC, a suggested title: Flat Cornfield.

The mysterious Susanna cooks for a crowd:

Eggs Mahler: Obtain 432 eggs. Claim you have a thousand. Cook as many of the eggs as time permits. Invite people over. When they've had enough eggs, give them some more eggs. This really only needs to be done about once every twelve years.Samuel Vriezen keeps it simple:

Eggs Messaien: Brood.And from the Hardest-Working Supposedly-On-Hiatus Man in Show Business, Alex Ross:

Eggs Wuorinen: Music is much more complicated than eggs. It is a typical travesty of the "I Pod" generation to talk about serious music of a problematical character in relation to eggs. Moreover, in the wake of twelve-note composition, eggs have become superfluous. But, if eggs must be made, scramble them vigorously for nineteen minutes.Finally, from the palate of Daniel Wolf, an actual recipe. I'll name it appropriately:

Eggs Wolf: Take one ostrich, one duck, and one quail egg. Store them refrigerated, tip downward, for at least 24 hours (to insure that the yolks are centered). Hard boil the eggs, each at the appropriate time length, scare with cold water and peel and slice in half lengthways immediately to avoid greying. Remove yolks and mash them until smooth with a bit of mayonnaise, toasted and ground spices (fenugreek, cayenne, mustard, cumin, coriander), one finely chopped small dill pickle and salt to taste. Now place the the quail egg white within the duck egg white, and that within the ostrich egg white, with a healthy layer of the yolk mixture between the white layers and in the quail egg white. Garnish with sweet paprika powder and fresh fenugreek and coriander leaves.Again, read 'em all if you haven't: they're all good. Thanks also to Alistair, Mike, Marc, and Zachary, who, like Susanna, are but names—if any of you have a web presence you'd like me to link to, e-mail me and I'll update the post. (And, from Matt Van Brink, don't miss the Steakhausen compendium of puns.)

December 15, 2006

The song that goes like this

Colin had a good post over at NewMusicBox this week about giving pieces titles (an unusually fine comment thread, as well). He takes Penderecki to task for his opportunism* in renaming the originally abstract "Threnody" to be a remembrance of the victims of Hiroshima, but concedes that it was a canny move: "I'd wager that the ugliest, most ear-splitting piece imaginable could win over a 21st century crowd if it had the perfect title."

Here's the problem/opportunity with titles on pieces of music: once you move outside the most bland and academic appellation—either a shout-out to the basic form (Sonata, Suite, etc.) or a list of who's playing (String Quartet, Symphony)—you're essentially using the language in a surreal way, and that sometimes results in a bit of cognitive dissonance with the piece itself. Describing music is a notoriously difficult challenge for language, and to sum up even the simplest piece in less than ten words is pretty much impossible. Which means any title you apply is a) somewhat disconnected from the piece, and, more interestingly, b) somewhat disconnected from itself: you're taking words that normally have agreed-upon meanings and putting them in a situation where either they become meaningless by virtue of their necessary inadequacy, or they're being used in a deliberately misleading way. Both results are traditionally surreal: the language is being alienated from itself, either directly or indirectly.

If your aesthetic is a surreal one, this isn't a problem; you can easily come up with titles that not only aren't jarringly incongruent with the music, but actually contribute to the overall effect. (Think of Satie.) But if your artistic goals are less informed by the powers and pleasures of absurdity, titles can be a tricky business. The safe way to go is the previously mentioned bland and academic path, but of course, you're surrounded by people telling you that you need to do more to get people interested in your music, that you need to grab their attention and get them to want to hear what you've written. They've got a point: the marketing possibilities of an effective title are not inconsiderable, and few of us have trust funds that would enable a willful ignorance of the realities of the marketplace. But if you're not referencing an artistic tradition (like Surrealism) where a certain amount of bait-and-switch is not only expected, but welcomed, you run the risk of disappointing the guileless and annoying the skeptical: if you call your offering "Elegy to 9/11," plenty of people will find it to be a shallow experience compared with their expectations, and plenty of others will find it to be nothing more than a cheap stunt.

What can you do? You can set texts: naming the piece after the poem that's being sung shifts the above burdens to the poet. (This can work for non-vocal music as well: find a pre-existing literary title or quotation that has a vague connection to your piece, and it has a certain inoculating effect. Boulez does this all the time; I've resorted to it on occasion.) You can take refuge in a certain hip snarkiness: the Bang On a Can types do this a lot, and often quite well, coming up with titles that are just abrasive and anti-establishment enough to give the expectation of listening that frisson of sitting at the cool table in the cafeteria. You can opt for puns: titles become such obvious and deliberate jokes that they detach themselves from the piece, and become more of an intellectual amuse-bouche for the listener. (Milton Babbitt and Michael Gandolfi are the acknowledged masters of the practice.) You can reference events or relationships so private that the audience is completely locked out of determining the appropriateness of your choice. (Think of every piece you've ever heard with a title like "For [person known only to the composer].") Or you could go ahead and name-drop a great event/historical figure/tragedy, and hope that you get away with it. (It worked for Penderecki, in spades.)

I guess I'm lucky in that my own music seems to lend itself to a certain amount of leeway in creative titling, but that's probably because my musical taste has also been heavily influenced by my literary taste, which does run towards the surreal. I like linguistically alienating effects; I like focusing on the meanings of individual words out of context; I like the poetic point where one can slip back and forth between the sounds of words and the meanings of words a little too easily. So it's only natural that I also like playing in the space between a piece of music and its title. But I'll admit that the ground there gets a little slippery at times.

*Update (12/17): as Alex Ross rightly points out in the comments, how responsible we should hold Penderecki for the renaming is unclear given the murky moral ground of totalitarian Poland.

Here's the problem/opportunity with titles on pieces of music: once you move outside the most bland and academic appellation—either a shout-out to the basic form (Sonata, Suite, etc.) or a list of who's playing (String Quartet, Symphony)—you're essentially using the language in a surreal way, and that sometimes results in a bit of cognitive dissonance with the piece itself. Describing music is a notoriously difficult challenge for language, and to sum up even the simplest piece in less than ten words is pretty much impossible. Which means any title you apply is a) somewhat disconnected from the piece, and, more interestingly, b) somewhat disconnected from itself: you're taking words that normally have agreed-upon meanings and putting them in a situation where either they become meaningless by virtue of their necessary inadequacy, or they're being used in a deliberately misleading way. Both results are traditionally surreal: the language is being alienated from itself, either directly or indirectly.

If your aesthetic is a surreal one, this isn't a problem; you can easily come up with titles that not only aren't jarringly incongruent with the music, but actually contribute to the overall effect. (Think of Satie.) But if your artistic goals are less informed by the powers and pleasures of absurdity, titles can be a tricky business. The safe way to go is the previously mentioned bland and academic path, but of course, you're surrounded by people telling you that you need to do more to get people interested in your music, that you need to grab their attention and get them to want to hear what you've written. They've got a point: the marketing possibilities of an effective title are not inconsiderable, and few of us have trust funds that would enable a willful ignorance of the realities of the marketplace. But if you're not referencing an artistic tradition (like Surrealism) where a certain amount of bait-and-switch is not only expected, but welcomed, you run the risk of disappointing the guileless and annoying the skeptical: if you call your offering "Elegy to 9/11," plenty of people will find it to be a shallow experience compared with their expectations, and plenty of others will find it to be nothing more than a cheap stunt.

What can you do? You can set texts: naming the piece after the poem that's being sung shifts the above burdens to the poet. (This can work for non-vocal music as well: find a pre-existing literary title or quotation that has a vague connection to your piece, and it has a certain inoculating effect. Boulez does this all the time; I've resorted to it on occasion.) You can take refuge in a certain hip snarkiness: the Bang On a Can types do this a lot, and often quite well, coming up with titles that are just abrasive and anti-establishment enough to give the expectation of listening that frisson of sitting at the cool table in the cafeteria. You can opt for puns: titles become such obvious and deliberate jokes that they detach themselves from the piece, and become more of an intellectual amuse-bouche for the listener. (Milton Babbitt and Michael Gandolfi are the acknowledged masters of the practice.) You can reference events or relationships so private that the audience is completely locked out of determining the appropriateness of your choice. (Think of every piece you've ever heard with a title like "For [person known only to the composer].") Or you could go ahead and name-drop a great event/historical figure/tragedy, and hope that you get away with it. (It worked for Penderecki, in spades.)

I guess I'm lucky in that my own music seems to lend itself to a certain amount of leeway in creative titling, but that's probably because my musical taste has also been heavily influenced by my literary taste, which does run towards the surreal. I like linguistically alienating effects; I like focusing on the meanings of individual words out of context; I like the poetic point where one can slip back and forth between the sounds of words and the meanings of words a little too easily. So it's only natural that I also like playing in the space between a piece of music and its title. But I'll admit that the ground there gets a little slippery at times.

*Update (12/17): as Alex Ross rightly points out in the comments, how responsible we should hold Penderecki for the renaming is unclear given the murky moral ground of totalitarian Poland.

Insomnia, with links

Lisa Boucher finds a really cool video.

Matt Van Brink finds a really small piano.

Elaine Fine finds a really awesome picture.

Daniel Wolf finds a really brilliant bedtime story—which I could use about now.

Matt Van Brink finds a really small piano.

Elaine Fine finds a really awesome picture.

Daniel Wolf finds a really brilliant bedtime story—which I could use about now.

December 14, 2006

Dreidel Attraction

Hanukkah begins at sundown tomorrow. As I've been out and about this holiday season, I've been pleased to see that the amount of cheap, impulse-buy Hanukkah tchotchkes has been on the rise—still nowhere near Christmas swag, but a noticeable uptick nonetheless. So the other day, I picked up one of these:

It's hollow plastic; inside is a battery, a sound chip, a couple of LEDs, and a spring-loaded switch. When you spin it, the centrifugal force closes the switch, and the thing lights up and plays a tinny electronic version of "The Dreidel Song." Clever.

The sound chip itself is somewhat primitive, though—by comparison, for my birthday last year, my inlaws got me a card (at right) that, when you open it, plays an excerpt from an actual orchestral recording of "Ride of the Valkyries." Pretty cool.

The sound chip itself is somewhat primitive, though—by comparison, for my birthday last year, my inlaws got me a card (at right) that, when you open it, plays an excerpt from an actual orchestral recording of "Ride of the Valkyries." Pretty cool.

Now, like most people, I'm ambivalent about Wagner—I mean, nice music and all, but oy vey, Richard, always with the anti-Semitism—and I'm not above giving the man a bit of a karmic wedgie when the opportunity presents itself.

So—hack apart the dreidel:

Recycle the chip from the birthday card:

Solder the new chip into the dreidel circuit:

And put the whole thing back together:

Here it is in action:

I love the smell of suganiyot in the morning!

It's hollow plastic; inside is a battery, a sound chip, a couple of LEDs, and a spring-loaded switch. When you spin it, the centrifugal force closes the switch, and the thing lights up and plays a tinny electronic version of "The Dreidel Song." Clever.

The sound chip itself is somewhat primitive, though—by comparison, for my birthday last year, my inlaws got me a card (at right) that, when you open it, plays an excerpt from an actual orchestral recording of "Ride of the Valkyries." Pretty cool.

The sound chip itself is somewhat primitive, though—by comparison, for my birthday last year, my inlaws got me a card (at right) that, when you open it, plays an excerpt from an actual orchestral recording of "Ride of the Valkyries." Pretty cool.Now, like most people, I'm ambivalent about Wagner—I mean, nice music and all, but oy vey, Richard, always with the anti-Semitism—and I'm not above giving the man a bit of a karmic wedgie when the opportunity presents itself.

So—hack apart the dreidel:

Recycle the chip from the birthday card:

Solder the new chip into the dreidel circuit:

And put the whole thing back together:

Here it is in action:

I love the smell of suganiyot in the morning!

December 13, 2006

Only twelve notes that a man can play

Courtesy of Kyle Gann, four minutes of Oscar Peterson playing an eight-bar blues of Lisztian transcendence. Jesus mercy.

Two of my heroes when I was a kid were Peterson, for reasons obvious to anyone who remembers what it's like to be a beginning pianist, and my dad, for (among other things) looking the other way when I essentially appropriated all of his Oscar Peterson records and played the hell out of them. He and my mom saw the man himself a few times when he would make periodic appearances at the London House in Chicago. I'm jealous.

Two of my heroes when I was a kid were Peterson, for reasons obvious to anyone who remembers what it's like to be a beginning pianist, and my dad, for (among other things) looking the other way when I essentially appropriated all of his Oscar Peterson records and played the hell out of them. He and my mom saw the man himself a few times when he would make periodic appearances at the London House in Chicago. I'm jealous.

"Si tu veux je te donnerai"

It's that time of year again—the shopping, the malls, the conspicuous consumption—you know, gift time. And you're completely stymied as to what to get the composer in your life. CDs? Pens? A paying job? Here's a few suggestions to help cross those remaining names off your list.

Is it baby's first Christmas / Hanukkah / Kwanzaa / Dies Natalis Solis Invicti? Soothe the little prodigy to sleep in the new year with a brand-new music box—a Stockhausen music box, that is! Yes, the tinkling sounds of one of the foremost avant-garde composers of our fractured modern world can inspire your infant to dream of being an angel made completely of light accompanying the vibrations of space and time themselves on a cosmic trumpet. Once they get to Kindergarten, imagine how quotidian the other children will seem! (Actually, when I was a toddler, I had a beloved music box that played the theme from "Camelot," and look how I turned out. Imagine if I had been winding up one of these.)

Is it baby's first Christmas / Hanukkah / Kwanzaa / Dies Natalis Solis Invicti? Soothe the little prodigy to sleep in the new year with a brand-new music box—a Stockhausen music box, that is! Yes, the tinkling sounds of one of the foremost avant-garde composers of our fractured modern world can inspire your infant to dream of being an angel made completely of light accompanying the vibrations of space and time themselves on a cosmic trumpet. Once they get to Kindergarten, imagine how quotidian the other children will seem! (Actually, when I was a toddler, I had a beloved music box that played the theme from "Camelot," and look how I turned out. Imagine if I had been winding up one of these.)

If all you want for Christmas is to escape your humdrum existence, you're in luck—now you can be Pulitzer-prize-winning composer Michael Colgrass for a day! Heck, you can be Michael Colgrass for the rest of your life once you find his entire archive of manuscripts and correspondence in your stocking. For a mere $135,000, you can fill your files with actual honored works commissioned by major ensembles, and leave a stack of mail from the likes of Sessions, Stravinsky, Cage, Copland, Persichetti, and Harold Pinter on your kitchen counter. Identity theft has never been so classy. Extra fun: go to town with a pencil and an eraser and hopelessly confuse generations of future musicologists!

If all you want for Christmas is to escape your humdrum existence, you're in luck—now you can be Pulitzer-prize-winning composer Michael Colgrass for a day! Heck, you can be Michael Colgrass for the rest of your life once you find his entire archive of manuscripts and correspondence in your stocking. For a mere $135,000, you can fill your files with actual honored works commissioned by major ensembles, and leave a stack of mail from the likes of Sessions, Stravinsky, Cage, Copland, Persichetti, and Harold Pinter on your kitchen counter. Identity theft has never been so classy. Extra fun: go to town with a pencil and an eraser and hopelessly confuse generations of future musicologists!

Know somebody who turns every backyard cookout into an immolation scene? Someone who sends every steak and chop to a charred, kerosene-scented Valhalla? Let them tend that magic fire in style with this Richard Wagner BBQ apron. Now your Saturday-afternoon Siegfried can grill those burgers until they're tougher than Nothung itself, and remain unmolested by the Fafner and Fasolt of spills and splatters—so that once your meal is plunged into a river of inedibility, he'll still be clean enough to take you out. (OK, OK, I'll stop now.)

Know somebody who turns every backyard cookout into an immolation scene? Someone who sends every steak and chop to a charred, kerosene-scented Valhalla? Let them tend that magic fire in style with this Richard Wagner BBQ apron. Now your Saturday-afternoon Siegfried can grill those burgers until they're tougher than Nothung itself, and remain unmolested by the Fafner and Fasolt of spills and splatters—so that once your meal is plunged into a river of inedibility, he'll still be clean enough to take you out. (OK, OK, I'll stop now.)

The female (or cross-dressing) scribbler on your list will love these "Composer" pumps by designer Richard Tyler. The shoe "features corset-style lacing" over a leopard-print insert—nothing says "music of the future" like faux-leopard bondage gear! Besides, it's "flirty"—and we all know how composers need to attract new audiences. (What? You want them to like you for your music? Good luck with that.)

The female (or cross-dressing) scribbler on your list will love these "Composer" pumps by designer Richard Tyler. The shoe "features corset-style lacing" over a leopard-print insert—nothing says "music of the future" like faux-leopard bondage gear! Besides, it's "flirty"—and we all know how composers need to attract new audiences. (What? You want them to like you for your music? Good luck with that.)

And finally, for the person who has everything, and thus is in desperate need of sabotage from jealous colleagues, head over to eBay for this copy of Pietro Deiro and Alfred d'Auberge's Atonal Studies for Accordion. After your successful composer tastes the forbidden fruit of the 12-tone squeezebox, everything else will seem bland and pointless—and the resulting string of Schoenbergian polkas will send that once-promising career further south than Roald Amundsen. (Honestly? I want this one bad. And the music box, too. I love that music box. And I've been pretty good this year! I mean, for me.)

And finally, for the person who has everything, and thus is in desperate need of sabotage from jealous colleagues, head over to eBay for this copy of Pietro Deiro and Alfred d'Auberge's Atonal Studies for Accordion. After your successful composer tastes the forbidden fruit of the 12-tone squeezebox, everything else will seem bland and pointless—and the resulting string of Schoenbergian polkas will send that once-promising career further south than Roald Amundsen. (Honestly? I want this one bad. And the music box, too. I love that music box. And I've been pretty good this year! I mean, for me.)

Is it baby's first Christmas / Hanukkah / Kwanzaa / Dies Natalis Solis Invicti? Soothe the little prodigy to sleep in the new year with a brand-new music box—a Stockhausen music box, that is! Yes, the tinkling sounds of one of the foremost avant-garde composers of our fractured modern world can inspire your infant to dream of being an angel made completely of light accompanying the vibrations of space and time themselves on a cosmic trumpet. Once they get to Kindergarten, imagine how quotidian the other children will seem! (Actually, when I was a toddler, I had a beloved music box that played the theme from "Camelot," and look how I turned out. Imagine if I had been winding up one of these.)

Is it baby's first Christmas / Hanukkah / Kwanzaa / Dies Natalis Solis Invicti? Soothe the little prodigy to sleep in the new year with a brand-new music box—a Stockhausen music box, that is! Yes, the tinkling sounds of one of the foremost avant-garde composers of our fractured modern world can inspire your infant to dream of being an angel made completely of light accompanying the vibrations of space and time themselves on a cosmic trumpet. Once they get to Kindergarten, imagine how quotidian the other children will seem! (Actually, when I was a toddler, I had a beloved music box that played the theme from "Camelot," and look how I turned out. Imagine if I had been winding up one of these.) If all you want for Christmas is to escape your humdrum existence, you're in luck—now you can be Pulitzer-prize-winning composer Michael Colgrass for a day! Heck, you can be Michael Colgrass for the rest of your life once you find his entire archive of manuscripts and correspondence in your stocking. For a mere $135,000, you can fill your files with actual honored works commissioned by major ensembles, and leave a stack of mail from the likes of Sessions, Stravinsky, Cage, Copland, Persichetti, and Harold Pinter on your kitchen counter. Identity theft has never been so classy. Extra fun: go to town with a pencil and an eraser and hopelessly confuse generations of future musicologists!

If all you want for Christmas is to escape your humdrum existence, you're in luck—now you can be Pulitzer-prize-winning composer Michael Colgrass for a day! Heck, you can be Michael Colgrass for the rest of your life once you find his entire archive of manuscripts and correspondence in your stocking. For a mere $135,000, you can fill your files with actual honored works commissioned by major ensembles, and leave a stack of mail from the likes of Sessions, Stravinsky, Cage, Copland, Persichetti, and Harold Pinter on your kitchen counter. Identity theft has never been so classy. Extra fun: go to town with a pencil and an eraser and hopelessly confuse generations of future musicologists! Know somebody who turns every backyard cookout into an immolation scene? Someone who sends every steak and chop to a charred, kerosene-scented Valhalla? Let them tend that magic fire in style with this Richard Wagner BBQ apron. Now your Saturday-afternoon Siegfried can grill those burgers until they're tougher than Nothung itself, and remain unmolested by the Fafner and Fasolt of spills and splatters—so that once your meal is plunged into a river of inedibility, he'll still be clean enough to take you out. (OK, OK, I'll stop now.)

Know somebody who turns every backyard cookout into an immolation scene? Someone who sends every steak and chop to a charred, kerosene-scented Valhalla? Let them tend that magic fire in style with this Richard Wagner BBQ apron. Now your Saturday-afternoon Siegfried can grill those burgers until they're tougher than Nothung itself, and remain unmolested by the Fafner and Fasolt of spills and splatters—so that once your meal is plunged into a river of inedibility, he'll still be clean enough to take you out. (OK, OK, I'll stop now.) The female (or cross-dressing) scribbler on your list will love these "Composer" pumps by designer Richard Tyler. The shoe "features corset-style lacing" over a leopard-print insert—nothing says "music of the future" like faux-leopard bondage gear! Besides, it's "flirty"—and we all know how composers need to attract new audiences. (What? You want them to like you for your music? Good luck with that.)

The female (or cross-dressing) scribbler on your list will love these "Composer" pumps by designer Richard Tyler. The shoe "features corset-style lacing" over a leopard-print insert—nothing says "music of the future" like faux-leopard bondage gear! Besides, it's "flirty"—and we all know how composers need to attract new audiences. (What? You want them to like you for your music? Good luck with that.) And finally, for the person who has everything, and thus is in desperate need of sabotage from jealous colleagues, head over to eBay for this copy of Pietro Deiro and Alfred d'Auberge's Atonal Studies for Accordion. After your successful composer tastes the forbidden fruit of the 12-tone squeezebox, everything else will seem bland and pointless—and the resulting string of Schoenbergian polkas will send that once-promising career further south than Roald Amundsen. (Honestly? I want this one bad. And the music box, too. I love that music box. And I've been pretty good this year! I mean, for me.)

And finally, for the person who has everything, and thus is in desperate need of sabotage from jealous colleagues, head over to eBay for this copy of Pietro Deiro and Alfred d'Auberge's Atonal Studies for Accordion. After your successful composer tastes the forbidden fruit of the 12-tone squeezebox, everything else will seem bland and pointless—and the resulting string of Schoenbergian polkas will send that once-promising career further south than Roald Amundsen. (Honestly? I want this one bad. And the music box, too. I love that music box. And I've been pretty good this year! I mean, for me.)

December 12, 2006

Variations

All was happy-go-lucky joy; and, at two o’clock, as Branton Hills’ Municipal Band, (a part of Gadsby’s Organization of Youth’s work, you know) struck up a bright march, not a glum physiognomy was found in all that big park.

Gadsby and Lucy had much curiosity in watching what such crashing music would do to various animals. At first a spirit akin to worry had baboons, gorillas, and such, staring about, as still as so many posts; until, finding that no harm was coming from such sounds, soon took to climbing and swinging again. Stags, yaks and llamas did a bit of high-kicking at first; Gadsby figuring that drums, and not actual music, did it. But a lilting waltzing aria did not worry any part of this big zoo family; in fact, a fox, wolf and jackal, in a quandary at first actually lay down, as though music truly “hath charms to calm a wild bosom.”—Ernest Vincent Wright,

Gadsby, 1939

IGOR STRAVINSKY was such a firebird that he loved going to the zoo "to watch the wild animals at feeding time, when they devoured the raw meat.""Shadows From a Lunarium,"

Time Magazine, February 24, 1958

(review of First Person Plural by Dagmar Godowsky)

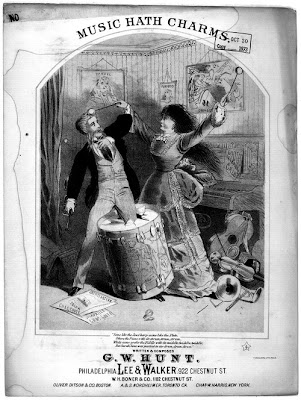

Some say that music hath charms

To soothe the savage beast

I've also heard some people say

That enough is as good as a feast

Now I once paid court to a maid

I'd have stuck to her too, like gum

But she went music mad, alas

Thro' her violent taste for the drumG.W. Hunt, "Music Hath Charms"

December 11, 2006

To Serve Man

It's the time of year when people show up at your house and you have to feed them, so I've been using my brief snatches of spare time to browse through cookbooks. One of my favorites (partially because it tends toward the impractical) is the venerable Larousse Gastronomique. One of the fun things about it, at least the old edition: it's got a fair amount of food named after composers.

Most chef wannabes know about dishes named for Rossini: take just about any foodstuff, cover it with a Madiera sauce, and garnish it with truffles and sautéed foie gras, and voila! you've got [foodstuff] Rossini. But there's more where that came from, and, oddly, most of them seem to be egg dishes. Here's a few:

Most chef wannabes know about dishes named for Rossini: take just about any foodstuff, cover it with a Madiera sauce, and garnish it with truffles and sautéed foie gras, and voila! you've got [foodstuff] Rossini. But there's more where that came from, and, oddly, most of them seem to be egg dishes. Here's a few:

Oeufs Auber: Stuffed halved tomatoes with a chicken forcemeat mixed with chopped truffles. Top each tomato with a soft-boiled or poached egg. Make a velouté sauce (white sauce) flavored with tomato paste; at the last minute, add a julienne of truffles that have been cooked in sherry. Cover the eggs with the sauce.I love offal, so that last one actually sounds pretty good to me. And the eggs Berlioz might make a fun weekend project the next time I'm in an Asian grocery that carries cock's combs. But notice: every one of these composers has been dead for a century or more. All the composers who came after—what are they? Chopped liver? Literally? No, we have to fix this.

Oeufs Berlioz: Make some oval croustades from Duchesse potato mixture, and brown them in the oven. Fill the croustades with a salpiçon of truffles and mushrooms blended with a thick Madiera sauce. Top each croustade with a soft-boiled or poached egg. Lightly cover the eggs with a sauce Suprême (velouté enriched with cream). Fill the middle of the dish with fried cock's combs à la Villeroi (poached in court-boullion and dredged in breadcrumbs).

Oeufs Bizet: Butter individual molds and line them with finely chopped pickled tongue and truffles. Break an egg into each mold and poach them in a bain-marie. Cook some artichoke hearts in butter. Unmold the eggs and place one on each artichoke heart. Cover with a Périgueux sauce (demi-glace with chopped truffles). Garnish each egg with a slice of truffle.

Oeufs Meyerbeer: Garnish shirred eggs with grilled lamb kidney. Surround the eggs with a ring of Périgueux sauce.

Eggs Carter: Break an egg into a pan with a multitude of other ingredients, and place on the stove. Continually and simultaneously vary both the temperature and the cooking time. The dish is done when the aggregate intervals of the other ingredients allegorically crush the individuality of the egg.Who have I forgotten? Leave 'em in the comments, and I'll post the most appetizing ones.

Eggs Ives: Cook the egg in water, clear water from a mountain lake that a dilettante might try to write a song about. Boil it—hard-boil it—until the yolk is a firm yellow globe—a sun shining on manly hearts with cleaned-out ears. Sissies like a runny yolk, but real beauty—natural beauty—is not to be found in liquidy prettiness—the pale imitations of the passing spectacle must give way to the hard truths of the soul. Emerson once said, "Yonder masterful cuckoo / Crowds every egg out of the nest."

Eggs Feldman: Extremely soft-boiled. Durations are free.

Eggs Nancarrow: That's huevos Nancarrow, you stupid gringo!

Eggs Partch: Build your own oven. Calibrate both the thermostat and the timer to non-Western scales of your own invention. Then bake the eggs at 943 degrees for 17,000 minutes, or until the yolks are set. Top each egg with a slice of peyote.

Eggs Rorem: January 23—Dinner at Lenny and Felicia's with Judy Collins, Edward Albee, the Carters, Virgil, Gore, and Mayor Lindsay, who seemed to have wandered into the wrong apartment. Every course made from eggs, a typical Bernstein obsession that will burn bright and then fade by next week. At the end of dessert, Lenny pulls out a chafing dish and, with Hollywood flair, announces that he will make eggs in the true Parisian style, which he then attempts with American ingredients. When the Vicomtesse showed me how to make eggs, she only used Parisian ingredients. I know these ingredients exist, because I saw them when I was in Paris. I leave early, fleeing into the gray city snow. I must send an apologetic card to Felicia tomorrow. The snow makes one sad; the whole world looks fragile, like an eggshell.

Eggs Schwantner: Crack an egg into a crystal goblet. Run a moistened finger around the rim of the goblet until the egg is vibrating at the same frequency as background radiation from the Big Bang. Serve on a bed of maj7(#11) chords.

Eggs Strauss: Give an egg to a singer. Cover with the orchestra.

Eggs Zorn: Cook as many eggs as you like in as many different ways as you can think of. Serve them all on the same plate. Garnish with matzo.

Eggs Soho the Dog: Do a Google search for "egg recipes." Pick the funniest one. Link to it. Repeat five times a week.

Sing, Sing, Sing

I told you not to mess with the Freemasons! Booing drives Alagna out of the La Scala Aida in a fit of petulance: Opera Chic has the marvelous details here, here, here, here, and here. (My, that is silly of me: just go here and scroll down.) I like applause as much as anyone, but I have to say my two favorite audience reactions are booing and dead silence: with the latter, you know you've got them, and with the former, well, better sincere booing than polite applause anyday.

Now, if you're going to cause an operatic scandal with offensive props, it might help to actually hang onto them. The Deutsche Oper Berlin has somehow lost the fake severed heads of Jesus, Buddha, Poseidon, and, most crucially, the prophet Mohammed from that off-again, on-again production of Idomeneo that got everyone into a frenzy. If those heads aren't up on eBay within the fortnight, the terrorists have won.

And in a break from silliness, Jeremy Eichler previews the upcoming CD release of the Lieberson Neruda Songs, and includes a sound clip, so you can see if it's really as special (Yes. Yes, it is) as everyone keeps telling you. (One of the borrowed studios I accompany in at Boston Conservatory still has a poster for a student recital by Victoria Livengood and Lorraine Hunt, which I always find an unusually touching artifact.)

Now, if you're going to cause an operatic scandal with offensive props, it might help to actually hang onto them. The Deutsche Oper Berlin has somehow lost the fake severed heads of Jesus, Buddha, Poseidon, and, most crucially, the prophet Mohammed from that off-again, on-again production of Idomeneo that got everyone into a frenzy. If those heads aren't up on eBay within the fortnight, the terrorists have won.

And in a break from silliness, Jeremy Eichler previews the upcoming CD release of the Lieberson Neruda Songs, and includes a sound clip, so you can see if it's really as special (Yes. Yes, it is) as everyone keeps telling you. (One of the borrowed studios I accompany in at Boston Conservatory still has a poster for a student recital by Victoria Livengood and Lorraine Hunt, which I always find an unusually touching artifact.)

December 08, 2006

Breezin'

Geoff Edgers passes along news and photos of Mother Nature having her revenge on Tanglewood, no doubt for all the global warming caused by those post-concert backups of BMWs and Lexuses extending from West Street all the way to the Pike. The bulk of the damage seems to be to Seranak, the old Koussevitsky estate (named for Serge and Natalie Koussevitsky—it strikes me that if the missus and I were to do the same thing, our house would be called "Chummagoo").

Full disclosure: I was a Tanglewood fellow the first year that they decided to house the composers at Miss Hall's School, rather than the comparatively swankier confines of Seranak, so I can't help feeling a little sense of karmic realignment. Ha! No, seriously, I have great memories of a couple of dinners up there—and the balcony is a breathtaking place to watch a storm roll in.

Full disclosure: I was a Tanglewood fellow the first year that they decided to house the composers at Miss Hall's School, rather than the comparatively swankier confines of Seranak, so I can't help feeling a little sense of karmic realignment. Ha! No, seriously, I have great memories of a couple of dinners up there—and the balcony is a breathtaking place to watch a storm roll in.

"Another year older, and deeper in debt"

Geoff Pullum at Language Log wishes a happy birthday to Noam Chomsky—and explains why singing the appropriate song is more appropriate than you might think.

Meanwhile, Tears of a Clownsilly embarks on an unusually long slide into senility and decrepitude. Now that it's all downhill from here, just think what you'll save on gas!

Meanwhile, Tears of a Clownsilly embarks on an unusually long slide into senility and decrepitude. Now that it's all downhill from here, just think what you'll save on gas!

Hope That I Get Old Before I Die

I have no secret Romantic desire to die young. Some artistic types do, at least in a half-hearted way, but not me—and it's not just that I'm greatly looking forward to being old and crotchety. The problem is, if you die young, then initial historical judgement is passed on you by your contemporaries, and often they can't get past their initial impression of you, no matter how misleading.

I was thinking about this after playwright George Hunka posted a link to this page, where the Canadian Broadcasting Company has streamed a bunch of excerpts from Glenn Gould's radio documentaries. If you've never heard these before, you're in for a treat—Gould's programs (on mostly non-musical subjects) are still ahead of their time, and entertaining as all get out.

Now, Gould (who died at the age of 50) is primarily remembered as a pianist and an eccentric, and often the latter more than the former. That's because his posthumous reputation was shaped by people whose opinions were no doubt colored by memories of his first major public appearances in the 1950's. Gould must have seemed like an alien—he came more or less out of nowhere, with a fully formed style that owed little to any existing school, and a collection of physical mannerisms that no doubt nearly upstaged his music-making. But his astonishing radio work (not to mention his engaging writings, as well as his film and television work) is a reminder that Gould was the real thing, a genius and a conscientious workaholic whose eccentricities were really the least interesting thing about him. Gould would have turned 75 this year, an age at which many musicians are still fully active; no doubt he would have had the opportunity to enjoy being a hero or a villian to at least a couple of subsequent generations. (And here's one to think about: you know he would have had a blog.)

Here's another example. My church choir just started rehearsing one of our Christmas favorites, "There shall a star come out of Jacob," by Felix Mendelssohn. I've mentioned my love for Mendelssohn's music here before, and this is no exception. I could talk volumes about this chorus, but I'll just point out this short passage at measure 73, which might be one of the most perfectly realized tonal cadences of all time.

The D that the tenors linger over in 77 is an absolutely masterful stroke, coloring an otherwise textbook cadence with a lovely string of rich dissonances.

It's remarkable enough out of context, but in context, it's a catharsis of subtle but unmistakable power; Mendelssohn has spent the entire chorus preparing us for this moment. We've had fully-formed contrasting A and B sections, including a development where the melodies of both are ingeniously combined and played off of each other. The A material is soaring and lyrical, the B material darker and more violent, and it's only at measure 79 that the lyricism wins out. And we know it, because it's the first full V-I cadence in tonic since measure 10, and only the second one of the entire piece. (That's long-range planning.) But that's not even the true genius of this moment. The true genius is that it's not the end of the piece. Mendelssohn has engineered this cadence to be but an exquisite curtain-raising for the coda: a simple but luminous harmonization of the old chorale tune "Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern."

In other words, this is the work of a composer at the absolute top of his or anybody else's game, writing music that unfolds its considerable glories with an effortless sure-footedness. This chorus, of course, is all that we have of Mendelssohn's planned oratorio Christus, left unfinished at his ridiculously premature death. Every time I hear that cadence, hear Mendelssohn at the point where his craft will finally let him do whatever he wants to do, I can't help thinking about the fact that it was, unwittingly, the end of his career. And you know what? I don't feel sadness, or regret, or wistfulness: I'm downright pissed, pissed that he didn't live to produce a normal life expectancy's allotment of music, pissed that he didn't get to let his imagination fly on the wings of his technical mastery, and pissed that he came to be remembered as simply a prodigy who had a certain flair for melody but somehow lacked the mettle and inner strength (you know, because he was a Jew) to excel in the "larger forms" that seemed to be the only criterion anybody knew how to apply in those days.

Which is why I fully intend to move heaven and earth in order to maintain my grip on this mortal coil. On the off chance that I actually get to the point Mendelssohn did, I want to be able to enjoy it for a while, and stick around long enough to supersede anyone's indelible memory of me as a callow youth. And if I never reach that point? You can call me a failure, but you'll have to do it to my wrinkled face.

I was thinking about this after playwright George Hunka posted a link to this page, where the Canadian Broadcasting Company has streamed a bunch of excerpts from Glenn Gould's radio documentaries. If you've never heard these before, you're in for a treat—Gould's programs (on mostly non-musical subjects) are still ahead of their time, and entertaining as all get out.

Now, Gould (who died at the age of 50) is primarily remembered as a pianist and an eccentric, and often the latter more than the former. That's because his posthumous reputation was shaped by people whose opinions were no doubt colored by memories of his first major public appearances in the 1950's. Gould must have seemed like an alien—he came more or less out of nowhere, with a fully formed style that owed little to any existing school, and a collection of physical mannerisms that no doubt nearly upstaged his music-making. But his astonishing radio work (not to mention his engaging writings, as well as his film and television work) is a reminder that Gould was the real thing, a genius and a conscientious workaholic whose eccentricities were really the least interesting thing about him. Gould would have turned 75 this year, an age at which many musicians are still fully active; no doubt he would have had the opportunity to enjoy being a hero or a villian to at least a couple of subsequent generations. (And here's one to think about: you know he would have had a blog.)

Here's another example. My church choir just started rehearsing one of our Christmas favorites, "There shall a star come out of Jacob," by Felix Mendelssohn. I've mentioned my love for Mendelssohn's music here before, and this is no exception. I could talk volumes about this chorus, but I'll just point out this short passage at measure 73, which might be one of the most perfectly realized tonal cadences of all time.

The D that the tenors linger over in 77 is an absolutely masterful stroke, coloring an otherwise textbook cadence with a lovely string of rich dissonances.

It's remarkable enough out of context, but in context, it's a catharsis of subtle but unmistakable power; Mendelssohn has spent the entire chorus preparing us for this moment. We've had fully-formed contrasting A and B sections, including a development where the melodies of both are ingeniously combined and played off of each other. The A material is soaring and lyrical, the B material darker and more violent, and it's only at measure 79 that the lyricism wins out. And we know it, because it's the first full V-I cadence in tonic since measure 10, and only the second one of the entire piece. (That's long-range planning.) But that's not even the true genius of this moment. The true genius is that it's not the end of the piece. Mendelssohn has engineered this cadence to be but an exquisite curtain-raising for the coda: a simple but luminous harmonization of the old chorale tune "Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern."

In other words, this is the work of a composer at the absolute top of his or anybody else's game, writing music that unfolds its considerable glories with an effortless sure-footedness. This chorus, of course, is all that we have of Mendelssohn's planned oratorio Christus, left unfinished at his ridiculously premature death. Every time I hear that cadence, hear Mendelssohn at the point where his craft will finally let him do whatever he wants to do, I can't help thinking about the fact that it was, unwittingly, the end of his career. And you know what? I don't feel sadness, or regret, or wistfulness: I'm downright pissed, pissed that he didn't live to produce a normal life expectancy's allotment of music, pissed that he didn't get to let his imagination fly on the wings of his technical mastery, and pissed that he came to be remembered as simply a prodigy who had a certain flair for melody but somehow lacked the mettle and inner strength (you know, because he was a Jew) to excel in the "larger forms" that seemed to be the only criterion anybody knew how to apply in those days.

Which is why I fully intend to move heaven and earth in order to maintain my grip on this mortal coil. On the off chance that I actually get to the point Mendelssohn did, I want to be able to enjoy it for a while, and stick around long enough to supersede anyone's indelible memory of me as a callow youth. And if I never reach that point? You can call me a failure, but you'll have to do it to my wrinkled face.

December 07, 2006

No, it's not about Glazunov

Most Dances Properly Conducted until Liquor begins to take EffectAll I can say is, if I ever write an homage to the Bach suites, I know what each movement will be called.

All the investigators report that up to about eleven p.m., generally speaking, the dances are well conducted; the crowd then begins to show the effect of too much liquor. Men and women become intoxicated and dance indecently such dances as “Walkin' the Dog,” “On the Puppy's Tail,” “Shaking the Shimmy,” “The Dip,” “The Stationary Wiggle,” etc. In some instances, little children—of whom there are often large numbers present—are given liquor and become intoxicated, much to the amusement of their elders. Many of them are forgotten by their parents in the excitement of the dance, and play upon the filthy floor, witnesses of all kinds of degradation.—Louise de Koven Bowen,

The Public Dance Halls of Chicago

(Chicago, 1917)

December 06, 2006

War Is Peace; Freedom Is Slavery; Major Is Minor

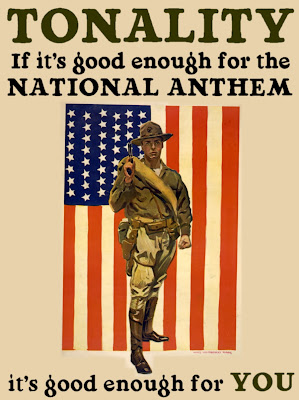

I was poking around the National Archives the other day, and I came across this:

If you ever needed proof of federal indifference to the musical arts, there you have it; that is the most overcooked canned lima bean of a propaganda poster I've ever seen. Music inspires... what, exactly? Gazing into the sky? Greek revival fashions? And is that woman having a hallucination of a marching band? Good heavens.

Frankly, I expect more from our government fearmongers. For the taxes we're paying, they ought to be able to scare a few composers:

And singers:

And audience members:

Ahhhh... being frightened into conformity is so comforting, isn't it?

If you ever needed proof of federal indifference to the musical arts, there you have it; that is the most overcooked canned lima bean of a propaganda poster I've ever seen. Music inspires... what, exactly? Gazing into the sky? Greek revival fashions? And is that woman having a hallucination of a marching band? Good heavens.

Frankly, I expect more from our government fearmongers. For the taxes we're paying, they ought to be able to scare a few composers:

And singers:

And audience members:

Ahhhh... being frightened into conformity is so comforting, isn't it?

December 05, 2006

One for all