Reviewing [nec]shivaree.

Boston Globe, February 28, 2007.

I'm paranoid about word counts, so I can never include all the players, but here's a shout-out to everyone else who didn't get a mention in the paper:

In the Wolff Exercises:

Nicole Barnes, saxophone

Joseph Becker, percussion

Derek Beckvold, saxophone/percussion

Danilo Henriquez, trumpet/percussion

Mary Joy Patchett, saxophone

Mark Plummer, trombone

Lauren Strobel, trumpet

In the Lucier Kettles:

Joseph Becker, Kevin Kosnik, Rieko Koyama, Jeffrey Means, George Nickson, timpani

Jeremy Sarna, sound engineer

Their next show is March 6. And it's free. Best deal in town.

February 28, 2007

Resolution Management

Reviewing the Boston Philharmonic.

Boston Globe, February 28, 2007.

Boston Globe, February 28, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

February 27, 2007

Music would play and Felina would whirl

The Hatto scandal may have stumbled to a premature close (Geoff Edgers has a nice summary in today's Globe), but the thievery bug seems to be spreading: according to a report in the El Paso Times, someone absconded with percussionist David Cossin's notes after a performance of Tan Dun's Concerto for Water Percussion with the El Paso Symphony on Saturday. (That's Cossin there, getting his hands wet in Germany last year.) The article isn't clear, but it sure sounds like the pilfered loot was Cossin's marked-up score, which would be a pretty egregious loss indeed: I've hung on to piano music that's barely readable and being held together with three kinds of tape solely because they've got fingerings and markings from Professor Paperno (including the dreaded green marker for when I missed something more than two weeks in a row). It may look like chicken scratches to you—it's autobiography to us.

The Hatto scandal may have stumbled to a premature close (Geoff Edgers has a nice summary in today's Globe), but the thievery bug seems to be spreading: according to a report in the El Paso Times, someone absconded with percussionist David Cossin's notes after a performance of Tan Dun's Concerto for Water Percussion with the El Paso Symphony on Saturday. (That's Cossin there, getting his hands wet in Germany last year.) The article isn't clear, but it sure sounds like the pilfered loot was Cossin's marked-up score, which would be a pretty egregious loss indeed: I've hung on to piano music that's barely readable and being held together with three kinds of tape solely because they've got fingerings and markings from Professor Paperno (including the dreaded green marker for when I missed something more than two weeks in a row). It may look like chicken scratches to you—it's autobiography to us.The silver lining? According to the Times, Saturday's concert was sold out.

February 26, 2007

Tomorrow's News Today

PHILADELPHIA, February 26, 2008—Saying that "nobody conducts the music of dead white males like a dead white male," Philadelphia Orchestra Association President James Undercofler today announced that the late Fritz Reiner has been appointed as Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, starting this fall. Reiner replaces Chief Conductor Charles Dutoit, who abruptly resigned last November after accusing orchestra members of trying to kill him with a poison-laced soft pretzel.

The move ends months of speculation over the post, during which several other candidates, including Riccardo Muti, Simon Rattle, and Terry Bradshaw, were rumored to be finalists. "Muti was a strong candidate," Undercofler admitted, "but, seeing as how he was still walking and talking, we simply couldn't absolutely assure our subscribers that he wouldn't start programming a lot of contemporary music or unfamiliar repertoire. The corpse of Fritz Reiner brings an unbeatable combination of experience and predictability."

Some in the orchestra were upset by the announcement, which was made after only limited consultation with the Players' Committee. In addition, the musicians were skeptical of Mr. Reiner's ability to establish a "rapport" with the orchestra, having not conducted professionally since 1963. Reiner's sole audition was in December, when he was propped up in front of the ensemble for a rehearsal of Strauss's "Death and Transfiguration." Several players, who wished to remain anonymous, characterized his podium technique as "stiff" and "lacking vitality," although one member saw occasional flashes of the Reiner of old. "If anything, his beat's gotten bigger," he said.

The announcement is seen as a blow to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, who were said to be themselves courting Reiner for another term as their director. CSO president Deborah Card played down the rumors, saying, "We've long seen the need for our new director to be not just a superb musician, but an exceptional advocate for music in the community. Mr. Reiner's remains aren't going to be doing a whole lot of outreach." Card, however, had no comment when asked about local news reports that the orchestra had been in talks, through a medium, with the disembodied spirit of Leonard Bernstein.

The move ends months of speculation over the post, during which several other candidates, including Riccardo Muti, Simon Rattle, and Terry Bradshaw, were rumored to be finalists. "Muti was a strong candidate," Undercofler admitted, "but, seeing as how he was still walking and talking, we simply couldn't absolutely assure our subscribers that he wouldn't start programming a lot of contemporary music or unfamiliar repertoire. The corpse of Fritz Reiner brings an unbeatable combination of experience and predictability."

Some in the orchestra were upset by the announcement, which was made after only limited consultation with the Players' Committee. In addition, the musicians were skeptical of Mr. Reiner's ability to establish a "rapport" with the orchestra, having not conducted professionally since 1963. Reiner's sole audition was in December, when he was propped up in front of the ensemble for a rehearsal of Strauss's "Death and Transfiguration." Several players, who wished to remain anonymous, characterized his podium technique as "stiff" and "lacking vitality," although one member saw occasional flashes of the Reiner of old. "If anything, his beat's gotten bigger," he said.

The announcement is seen as a blow to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, who were said to be themselves courting Reiner for another term as their director. CSO president Deborah Card played down the rumors, saying, "We've long seen the need for our new director to be not just a superb musician, but an exceptional advocate for music in the community. Mr. Reiner's remains aren't going to be doing a whole lot of outreach." Card, however, had no comment when asked about local news reports that the orchestra had been in talks, through a medium, with the disembodied spirit of Leonard Bernstein.

February 24, 2007

Suffragette City

All right, I think it's time to get organized. One of our local classical stations, WCRB, is having an online poll to find Boston's "Top 100 Classical Pieces of all time." If you aren't familiar with WCRB's programming, I can sum it up by saying that the overwhelming favorites are probably "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" and something by Albinoni. Not that there's anything wrong with that, but said poll might be a way to get some more interesting fare in through the back door—they're going to broadcast the 100 top vote-getters next weekend. Time for some ballot-stuffing! In the interests of efficiency and not diluting the electoral voice of a generation, I propose drawing selections from the following list (which, apart from being limited to living American composers, has no real rhyme or reason, just stuff I would be tickled to hear as "Classics for Relaxation" programming):

Robert Ashley: In Sara Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women Milton Babbitt: Philomel Anthony Braxton: Composition #82 (For Four Orchestras) Elliott Carter: String Quartet no. 3 George Crumb: Black Angels Lukas Foss: Baroque Variations Philip Glass: Music in Twelve Parts Alvin Lucier: I Am Sitting In a Room Meredith Monk: Atlas Steve Reich: Four Organs Frederic Rzewski: The People United Will Never Be Defeated Charles Wuorinen: Third Piano Concerto

You'll need to enter a name, e-mail, and phone number, but considering how many actual dead people have cast ballots over the years in my home town of Chicago, that hardly seems an impediment to, well, gaming the system. Vote early, vote often!

You'll need to enter a name, e-mail, and phone number, but considering how many actual dead people have cast ballots over the years in my home town of Chicago, that hardly seems an impediment to, well, gaming the system. Vote early, vote often!

February 23, 2007

Radio radio

Hey, if you tune into WGBH right now (89.7 FM in Boston, streaming on the Web here), you can catch today's live Boston Symphony concert, which this week includes the world premiere performances of Kaija Saariaho's cello concerto, "Notes on Light." If you're keeping score at home, that's two BSO premieres in two weeks. Enjoy it while it lasts. (You can also hear tomorrow night's concert at 8 PM on WCRB.)

Critic-at-large Moe and I got ourselves good and lost in the Sherborn Town Forest this morning, and when we got back to the car, WGBH was rebroadcasting a portion of Garrick Ohlsson's Jordan Hall recital from a couple of weeks back. They were playing the Beethoven op. 22 Sonata, which was my favorite one on the program. It's Ludwig at his most relaxed and human, especially the last movement, which takes the traditional Classical opera buffa-style finale and turns it inside out; a cute number for the lovers that you're hearing from backstage, so you also get stagehands running around, scenery creaking into place, and quarrels among the extras. It's enough to make me wish he hadn't gone all Romantic-heroic on us.

WGBH sent around an e-mail the other day to announce that next Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday at 9 AM (EST), Cathy Fuller will be broadcasting (and streaming) the 1975 Houston Grand Opera recording of Scott Joplin's Treemonisha. Joplin's a hero around Soho the Dog HQ, so that's information we're happy to pass along.

Critic-at-large Moe and I got ourselves good and lost in the Sherborn Town Forest this morning, and when we got back to the car, WGBH was rebroadcasting a portion of Garrick Ohlsson's Jordan Hall recital from a couple of weeks back. They were playing the Beethoven op. 22 Sonata, which was my favorite one on the program. It's Ludwig at his most relaxed and human, especially the last movement, which takes the traditional Classical opera buffa-style finale and turns it inside out; a cute number for the lovers that you're hearing from backstage, so you also get stagehands running around, scenery creaking into place, and quarrels among the extras. It's enough to make me wish he hadn't gone all Romantic-heroic on us.

WGBH sent around an e-mail the other day to announce that next Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday at 9 AM (EST), Cathy Fuller will be broadcasting (and streaming) the 1975 Houston Grand Opera recording of Scott Joplin's Treemonisha. Joplin's a hero around Soho the Dog HQ, so that's information we're happy to pass along.

February 22, 2007

Faire Use

What with all the plagiarism this month, it seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most plagiarized composers of all time—at least in his own mind, that is. The perennially litigous Ira Arnstein, born in 1879, would only be remembered today, if at all, for a few not-unpleasant Tin Pan Alley and religious numbers from the 1920s, except for the fact that he was convinced that other, more successful songwriters were constantly ripping him off. Arnstein brought no less than five lawsuits between 1936 and 1946, against the likes of Harry Warren, Joe Burke, Cole Porter, and others; and in the process, he indirectly paved the way for a refined legal definition of music plagiarism, one that, for better or for worse, persists today.

Arnstein was born in Kiev, and emigrated to the United States when he was eleven. A sometime pianist, music teacher, and composer, by the 1930s, he had become something of a full-time plaintiff. His first effort, Arnstein v. Edward B. Marks Music Corp. (82 F. 2d 275 [2d Cir. 1936]), set the pattern: Arnstein would take a song of his own and another, more popular song, and, by highlighting selected pitches, altering rhythms, changing octaves, and elevating accompanying notes to melodic status, conjure similarities between them. Jack Lawrence had co-written one of the songs named in Arnstein's suit, "Play, Fiddle, Play." Lawrence recalls:

Undeterred, Arnstein next brought suit against ASCAP itself. Arnstein v. ASCAP (29 F. Supp. 388 [S.D.N.Y. 1939]) was much in the vein of his previous action, right down to Arnstein's familiar allegations of an enormous conspiracy to pirate his compositions. From his complaint:

Finally, though, Arnstein caught a break. For his final trip through the judicial system, Arnstein took aim at none other than Cole Porter. "Begin the Beguine" had been stolen from Arnstein's setting of "The Lord Is My Shepherd." "Don't Fence Me In" had lifted from Arnstein's "A Modern Messiah." "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" had its illicit origins in an Arnstein instrumental called "A Mother's Prayer." Arnstein had become accustomed to grants of summary judgement for the defendants—the presiding judge saying, basically, that there wasn't enough evidence to even bother with a jury trial—and he had always lost on appeal. But Arnstein v. Porter (154 F.2d 464 [2d Cir. 1946]) was, surprisingly, remanded for trial by the district court, and Arnstein got his chance in front of a jury. Of course, he lost—but it took some doing. Charles Schwartz relates in his biography of Porter:

In the absence of a direct confession, to establish the fact of copying, the plaintiff needs to show that the defendant had access to the pirated material, and that the material was actually pirated—that the pieces in question are, in fact, suspiciously similar. (Note that this makes all the evidence for this part of the test circumstantial.) The court recognized the tricky nature of the access question; if that couldn't be proved, the plaintiff could still satisfy the test if the similarities were "so striking as to preclude the possibility that the plaintiff and the defendant independently arrived at the same result." How striking would that be, exactly? Good question. And while the test says that the less evidence of access, the more obvious the similarities need to be, what no court has ever really cleared up is whether the relationship works in reverse—that is, whether more compelling evidence of access allows for less of a resemblance between the original and the alleged copy.

Demonstrating that the copying amounted to "improper appropriation" is an even stickier wicket. The plaintiff needs to show that what was stolen is what made the original piece distinct and memorable to the ear of "the ordinary lay hearer." That might seem reasonable—anyone can hear if two songs are the same, right? Maybe so, but most people aren't aware that a lot of what they're hearing may not actually be copyrightable. In legalese, such elements are called scènes à faire (literally, "scenes that must be made"), meaning they're so common to a given situation that they've lost any claim to distinction. To allege that one romantic comedy stole from another because they both end with weddings would fail on the grounds that such a denouement is a scène à faire for romantic comedies. So just because two songs both start on do, mi, or sol, or both end on a V-I cadence, or both use, say, a twelve-bar blues progression shouldn't be enough to establish plagiarism, but that's assuming the judge or jury are musically literate enough to know the basic building blocks of tonal music.

And here's where the system fails, because expert testimony on the question of improper appropriation is, at best, severely limited. Under Arnstein, a musical expert can only testify as to the hypothetical effect on that "ordinary lay hearer," completely ignoring any opinion as to whether perceived similarities are scènes à faire or not. (As it is, having an expert witness try to put him or herself into the mind of a non-expert may, in fact, violate Federal rules of evidence regarding expert testimony.) Under a later, non-music plagiarism decision, Sid and Marty Krofft v. McDonald's (562 F.2nd 1157 [9th Cir. 1977])—the first case to concern "total concept and feel" plagiarism—expert witnesses are simply excluded from the improper appropriation test. As lawyer (and trained composer) Jeffrey Cadwell points out in his article "Expert Testimony, Scènes à Faire, and Tonal Music: A (Not So) New Test for Infringement," this means that musicians are shut out of the very part of the process where they're most needed: establishing whether or not similarities between two works are proof of theivery or just part of a generic vocabulary.

Cadwell points out that the obvious solution—requiring proof of access and letting musical experts testify as to whether similarities between songs are trivial or not—was actually proposed prior to Arnstein, in a 1932 book on music copyright by Alfred Shafter. (Shafter's book, from what I've seen, contains a number of howlers on musical substance, but he correctly foresaw the difficulty courts would have in dealing with it.) And since mass media and digital distribution have made access more and more easy to assume, others have proposed taking the guesswork out of the access question via compulsory music use licenses: basically cheap, no-permission-needed shout-outs to copyright holders that a particular piece of music is being covered, sampled, or otherwise borrowed (see, for example, this article by J. Michael Keyes). Are any of these going to happen soon? Probably not—the wheels of justice do grind exceedingly fine, and judges historically don't like to admit that there's a subject matter that might be beyond their ken.

So what eventually happened to Arnstein? I don't know; after the Porter trial, he seems to have vanished—there were no further lawsuits, and I can't find any record of him after 1946. Wherever he is, though, he'd probably be pleased to know that he's still causing other composers legal troubles—if only indirectly.

Arnstein was born in Kiev, and emigrated to the United States when he was eleven. A sometime pianist, music teacher, and composer, by the 1930s, he had become something of a full-time plaintiff. His first effort, Arnstein v. Edward B. Marks Music Corp. (82 F. 2d 275 [2d Cir. 1936]), set the pattern: Arnstein would take a song of his own and another, more popular song, and, by highlighting selected pitches, altering rhythms, changing octaves, and elevating accompanying notes to melodic status, conjure similarities between them. Jack Lawrence had co-written one of the songs named in Arnstein's suit, "Play, Fiddle, Play." Lawrence recalls:

Arnstein's lawyer had a piano and fiddle player in court plus huge music charts, an intriguing presentation. The melody line of a song consists of single notes in the clef treble. Arnstein's chart highlighted notes in both the clef and bass and when the fiddler played only the highlighted notes... lo and behold! — it sounded exactly like our song! Our attorneys spent hours trying to explain this to the judge, but he would only accept what he was hearing.In fact, as you can compare for yourself via the Columbia Law Library's Music Plagiarism Project, the songs barely rate even a charitable resemblance. Arnstein didn't help his cause by admitting that he had threatened the defendants. The New York Herald Tribune reported Arnstein's testimony: "'I was desperate,' Arnstein said quaveringly. 'I heard my song being played everywhere, and I was starving. I was out of my mind and might have committed murder.'" (Lawrence remembered that Arnstein "paraded in front of the ASCAP offices wearing a sandwich sign that read: 'My songs have been plagiarized by the following writers: Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Rodgers and Hart.'") Theatrics aside, Arnstein's suit was eventually dismissed by the Second Circuit. (Judge Learned Hand took the opportunity to excoriate popular music in general, suggesting that pop songwriters were too witless to plagiarize: "[The defendant's] gifts were very limited, and to attribute to him the ingenuity and penetration so to truncate and modify, and thus really to create a melody out of other elements, is harder than to suppose that the extremely simple theme should have occurred to him out of his own mind.")

Undeterred, Arnstein next brought suit against ASCAP itself. Arnstein v. ASCAP (29 F. Supp. 388 [S.D.N.Y. 1939]) was much in the vein of his previous action, right down to Arnstein's familiar allegations of an enormous conspiracy to pirate his compositions. From his complaint:

That they have in cooperation with the other defendants and their attorneys conceived the plan of branding the complainant as a lunatic and have worked in harmony with the officers of ASCAP and MPPA (Music Publishers Protective Association) to oust the complainant from the W.P.A. and have caused him to starve.Arnstein managed to come up with two expert witnesses willing to testify that his song "Whisper to Me" bore certain resemblances to Joe Burke's "My Wishing Song," although the force of said testimony was blunted when the experts admitted under cross-examination that both songs bore certain resemblances to a previously existing number called "Are You Lonesome Tonight?" Arnstein similarly tried to sue BMI a few years later (Arnstein v. Broadcast Music, 137 F.2d 410 [2d Cir. 1943]), brazenly citing "Whisper to Me" again, this time comparing it to a tune called "It All Comes Back to Me Now." His next try, Arnstein v. Twentieth Century Fox Film (52 F. Supp. 114 [S.D.N.Y. 1943]), was his most far-fetched yet, asserting that Harry Warren's "I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo" had infringed Arnstein's Wagnerian parody chorus "Kalamazoo" pretty much on the grounds that they both mention the same city.

...

That his room was constantly ransacked and many manuscripts and letters stolen. When he complained to the Police Department no action was taken but two gorillas beat plaintiff up and plaintiff produced a Doctor's certificate at the trial to prove that he received medical attention for several weeks....

...

That the conspiracy extended even to the Court Room during the trial. Witnesses and Musicians were accosted by defendants attorneys and induced to disappear. That twenty-five (25) musicians from the Union who signed affidavits to the similarity of the Music, were given jobs in the Russian Ballet as an inducement for not testifying at this trial.

Finally, though, Arnstein caught a break. For his final trip through the judicial system, Arnstein took aim at none other than Cole Porter. "Begin the Beguine" had been stolen from Arnstein's setting of "The Lord Is My Shepherd." "Don't Fence Me In" had lifted from Arnstein's "A Modern Messiah." "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" had its illicit origins in an Arnstein instrumental called "A Mother's Prayer." Arnstein had become accustomed to grants of summary judgement for the defendants—the presiding judge saying, basically, that there wasn't enough evidence to even bother with a jury trial—and he had always lost on appeal. But Arnstein v. Porter (154 F.2d 464 [2d Cir. 1946]) was, surprisingly, remanded for trial by the district court, and Arnstein got his chance in front of a jury. Of course, he lost—but it took some doing. Charles Schwartz relates in his biography of Porter:

In the two-week long jury trial that followed, Monty Woolley, Deems Taylor, and Sigmund Spaeth all appeared in Cole's defense to support his contention that he had never taken material from Arnstein. Cole also testified that he neither knew Arnstein nor was familiar with his work. When the case finally went to the jury it was dismissed as being without merit after a deliberation of nearly two hours. But though Cole won the case, it was perhaps as a result of the experience gained from this trial that, when asked if he ever went out without a carnation in his boutonniere, Cole answered, "Only when I'm being sued, because a carnation in the buttonhole never helps your case before a jury."What changed? The Second District had decided to raise the bar for summary judgements, making it that much harder to simply dismiss nuisance lawsuits like Arnstein's. Now, the plaintiff was only required to demonstrate two things: a) that the defendant might have indeed copied from the plaintiff, and b) that the copying constituted "improper appropriation." Although subsequent case law has once again lowered the impediments to summary judgements, the Arnstein test remains the basis for music plagiarism cases. And both parts of the test are, well, complicated.

In the absence of a direct confession, to establish the fact of copying, the plaintiff needs to show that the defendant had access to the pirated material, and that the material was actually pirated—that the pieces in question are, in fact, suspiciously similar. (Note that this makes all the evidence for this part of the test circumstantial.) The court recognized the tricky nature of the access question; if that couldn't be proved, the plaintiff could still satisfy the test if the similarities were "so striking as to preclude the possibility that the plaintiff and the defendant independently arrived at the same result." How striking would that be, exactly? Good question. And while the test says that the less evidence of access, the more obvious the similarities need to be, what no court has ever really cleared up is whether the relationship works in reverse—that is, whether more compelling evidence of access allows for less of a resemblance between the original and the alleged copy.

Demonstrating that the copying amounted to "improper appropriation" is an even stickier wicket. The plaintiff needs to show that what was stolen is what made the original piece distinct and memorable to the ear of "the ordinary lay hearer." That might seem reasonable—anyone can hear if two songs are the same, right? Maybe so, but most people aren't aware that a lot of what they're hearing may not actually be copyrightable. In legalese, such elements are called scènes à faire (literally, "scenes that must be made"), meaning they're so common to a given situation that they've lost any claim to distinction. To allege that one romantic comedy stole from another because they both end with weddings would fail on the grounds that such a denouement is a scène à faire for romantic comedies. So just because two songs both start on do, mi, or sol, or both end on a V-I cadence, or both use, say, a twelve-bar blues progression shouldn't be enough to establish plagiarism, but that's assuming the judge or jury are musically literate enough to know the basic building blocks of tonal music.

And here's where the system fails, because expert testimony on the question of improper appropriation is, at best, severely limited. Under Arnstein, a musical expert can only testify as to the hypothetical effect on that "ordinary lay hearer," completely ignoring any opinion as to whether perceived similarities are scènes à faire or not. (As it is, having an expert witness try to put him or herself into the mind of a non-expert may, in fact, violate Federal rules of evidence regarding expert testimony.) Under a later, non-music plagiarism decision, Sid and Marty Krofft v. McDonald's (562 F.2nd 1157 [9th Cir. 1977])—the first case to concern "total concept and feel" plagiarism—expert witnesses are simply excluded from the improper appropriation test. As lawyer (and trained composer) Jeffrey Cadwell points out in his article "Expert Testimony, Scènes à Faire, and Tonal Music: A (Not So) New Test for Infringement," this means that musicians are shut out of the very part of the process where they're most needed: establishing whether or not similarities between two works are proof of theivery or just part of a generic vocabulary.

Cadwell points out that the obvious solution—requiring proof of access and letting musical experts testify as to whether similarities between songs are trivial or not—was actually proposed prior to Arnstein, in a 1932 book on music copyright by Alfred Shafter. (Shafter's book, from what I've seen, contains a number of howlers on musical substance, but he correctly foresaw the difficulty courts would have in dealing with it.) And since mass media and digital distribution have made access more and more easy to assume, others have proposed taking the guesswork out of the access question via compulsory music use licenses: basically cheap, no-permission-needed shout-outs to copyright holders that a particular piece of music is being covered, sampled, or otherwise borrowed (see, for example, this article by J. Michael Keyes). Are any of these going to happen soon? Probably not—the wheels of justice do grind exceedingly fine, and judges historically don't like to admit that there's a subject matter that might be beyond their ken.

So what eventually happened to Arnstein? I don't know; after the Porter trial, he seems to have vanished—there were no further lawsuits, and I can't find any record of him after 1946. Wherever he is, though, he'd probably be pleased to know that he's still causing other composers legal troubles—if only indirectly.

February 21, 2007

Lumen de lumine

A profile of Kaija Saariaho.

Boston Globe, February 21, 2007.

Boston Globe, February 21, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

February 20, 2007

Inside out, and round and round

Some things you might have missed while double-checking your Joyce Hatto CDs against your Liberace albums....

Anyone for a left-handed piano? Christopher Seed, the Jimi Hendrix of fortepianists, had a Dutch instrument maker build him a mirror-image piano, with the treble on the left side of the keyboard, in order to take advantage of his sinister inclinations. Admission: I'm a southpaw myself, but my main gauche still lags behind its more popular sibling in terms of technique, so I'm not sure how much this would help me. I would love to hear how the bulk of the repertoire sounds inverted around middle C, though. (courtesy of Bart at The Well-Tempered Blog).

Grammys? Boomer nostalgia trips. Oscars? Please. Pulitzers? Until they give one to Lukas Foss, I'll keep raising an eyebrow. No, the real honors come from Andy of The Black Torrent Guard, who's dishing out the hardware in his inaugural Most Annoying Song tournament. The winner? The legendary James Tenney, whose classic earworm "For Ann (rising)" beat out a Rachael Ray mixtape. Something to shoot for next year, although be forewarned: these are the big leagues. How tough is the competition? "Empty Chairs at Empty Tables" didn't even get an invite. Yikes.

Think you know Purcell's Come, Ye Sons of Art? No, you don't. According to Dr. Rebecca Herissone of the University of Manchester, Purcell's beloved piece fell victim to a less-than-diligent copyist in the mid-1700s, who "used different instruments, and changed repeats, notation and words and may even have replaced a whole movement with another Purcell piece." Herissone has attempted to restore Purcell's original intentions, although, lacking the ability to pop both CDs into the computer and compare their waveforms, she's had to resort to certain amount of well-informed conjecture.

OK, OK, I couldn't stay away from the Hatto thing. The latest: Hatto's husband finally speaks, and his non-denial denials show a certain flair and appreciation for the art. (Jessica and Lisa are good sources for updates.)

Anyone for a left-handed piano? Christopher Seed, the Jimi Hendrix of fortepianists, had a Dutch instrument maker build him a mirror-image piano, with the treble on the left side of the keyboard, in order to take advantage of his sinister inclinations. Admission: I'm a southpaw myself, but my main gauche still lags behind its more popular sibling in terms of technique, so I'm not sure how much this would help me. I would love to hear how the bulk of the repertoire sounds inverted around middle C, though. (courtesy of Bart at The Well-Tempered Blog).

Grammys? Boomer nostalgia trips. Oscars? Please. Pulitzers? Until they give one to Lukas Foss, I'll keep raising an eyebrow. No, the real honors come from Andy of The Black Torrent Guard, who's dishing out the hardware in his inaugural Most Annoying Song tournament. The winner? The legendary James Tenney, whose classic earworm "For Ann (rising)" beat out a Rachael Ray mixtape. Something to shoot for next year, although be forewarned: these are the big leagues. How tough is the competition? "Empty Chairs at Empty Tables" didn't even get an invite. Yikes.

Think you know Purcell's Come, Ye Sons of Art? No, you don't. According to Dr. Rebecca Herissone of the University of Manchester, Purcell's beloved piece fell victim to a less-than-diligent copyist in the mid-1700s, who "used different instruments, and changed repeats, notation and words and may even have replaced a whole movement with another Purcell piece." Herissone has attempted to restore Purcell's original intentions, although, lacking the ability to pop both CDs into the computer and compare their waveforms, she's had to resort to certain amount of well-informed conjecture.

OK, OK, I couldn't stay away from the Hatto thing. The latest: Hatto's husband finally speaks, and his non-denial denials show a certain flair and appreciation for the art. (Jessica and Lisa are good sources for updates.)

February 19, 2007

Pentiti, cangia vita / È l'ultimo momento!

"Doing a Mozart"? According to Jordan Tate, author of The Contemporary Dictionary of Sexual Euphemisms, that's slang for a horizontal gavotte of sufficient vigor to leave one's wig askew. According to the book:

I haven't read Tate's book, but my taste runs to actual etymologies, not half-baked stereotypes of classical music. (Check out the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang for a book that does it right.) And while Tate claims that the euphemisms themselves are authentic, and only the histories are made up, "doing a Mozart" sounds suspiciously pat to me.

Besides, in Chicago, "Mozart" has another range of reference that's far less cute. No doubt due to the influx of German immigrants in the 1800s, Chicago has a whole row of streets named after German cultural heroes: Schiller, Goethe, Schubert, Mozart. And the intersection of Mozart Street (pronounced with a soft "z," by the way) and Augusta Boulevard, out by Humboldt Park, marks the center of territory controlled by the Insane Dragons street gang (who have their own web page—those Chicago gangs are organized). According to that page, Mozart and Augusta is known as the "Dragon's Pit," and the locale rates its own entry at UrbanDictionary.com. I'm hardly an expert on gangland Chicago, but even I knew that being out around Humboldt Park after dark was liable to leave your wig askew.

It was deemed necessary to have a euphemism named after Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, due to his rock-star-like behavior in [the movie Amadeus]. The youth culture of Chicago started using this euphemism as a sign of respect for the somewhat timid or classy music (which was revolutionary in its time) and the juxtaposition of a wild and carnal celebrity.Which is all nonsense, Tate says in this interview. "I made up all the histories. Every word of it. There was no scholarship. You can't really prove where a euphemism came from. I used whatever I felt was most plausible, and some of the true facts really came together in a way I appreciated."

I haven't read Tate's book, but my taste runs to actual etymologies, not half-baked stereotypes of classical music. (Check out the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang for a book that does it right.) And while Tate claims that the euphemisms themselves are authentic, and only the histories are made up, "doing a Mozart" sounds suspiciously pat to me.

Besides, in Chicago, "Mozart" has another range of reference that's far less cute. No doubt due to the influx of German immigrants in the 1800s, Chicago has a whole row of streets named after German cultural heroes: Schiller, Goethe, Schubert, Mozart. And the intersection of Mozart Street (pronounced with a soft "z," by the way) and Augusta Boulevard, out by Humboldt Park, marks the center of territory controlled by the Insane Dragons street gang (who have their own web page—those Chicago gangs are organized). According to that page, Mozart and Augusta is known as the "Dragon's Pit," and the locale rates its own entry at UrbanDictionary.com. I'm hardly an expert on gangland Chicago, but even I knew that being out around Humboldt Park after dark was liable to leave your wig askew.

February 17, 2007

Imitation of life

Barring any sudden revelations involving Riccardo Muti, a beautiful disaffected ex-KGB agent, and a briefcase full of uranium (TOTALLY MADE-UP STORY, although can't you just see Muti in a plot like that?), the Joyce Hatto brouhaha is certainly shaping up to be the classical music scandal of the year. Just in case you were submerged in therapeutic mud for the past couple of days, here's the gist: a recluse who lost a long battle with cancer last year, Ms. Hatto nonetheless became a cult favorite among aficionados on the basis of her 100+ CDs released on the tiny Concert Artists label. A great story: a musician, initially denied her chance at greatness, perseveres through her physical difficulty to create a lasting contribution to the art. However, as the magazine Gramophone first reported on Thursday, a handful of those recordings have been revealed as spurious, concocted by repackaging other pianists' previously existing recordings with slight digital alterations. The evidence is persuasive, to say the least—and it seems likely that more examples are to come. (Lisa Hirsch has all the pertinent links.)

Now I have a fondness for well-executed or particularly brazen hoaxes and forgeries, which I've touched on before. What's interesting to me about this one is that although the words fraud, fake, and hoax have been bandied about quite a bit, as far as I can tell, in the initial reports, only Alan Riding's write-up in the New York Times (which Jerry at Sequenza21 wittily purloined) calls the situation what it is: plagiarism. Most forgeries involve taking your own work and passing it off as somebody else's, usually somebody more famous than you. This, if the allegations pan out, is just the opposite: taking someone else's work and passing it off as your own.

I'm not surprised that the hoax went undetected for so long. I like to think that I have reasonably savvy ears, but I would doubt my own ability to hear the deception, unless I was specifically listening for it—and who listens to music that way? (To their credit, some people were suspicious from the first.) What's really intriguing is that no one else (to my knowledge, at least) has tried this before. It would seem to me that classical music recording would provide great opportunities for plagiarism. Why? Because the logistics of performance are pretty close to plagiarism already. Even though there's no attempt at deception, and there's full attribution, a pianist playing the Transcendental Etudes is using notes, rhythms, and dynamics set down by Liszt—and, at least textually, nothing else. Any two performances of the same piece are going to be largely the same. Of course, the artistry lies in the slight differences; but what the individual performer brings to the table is a historical anomaly, something that has persisted in music long after the notion of plagiarism erased it from other intellectual pursuits.

In 1747, the English poet John Milton was accused by one William Lauder of plagiarising much of Paradise Lost from a 1654 Latin poem by Jacobus Masenius. The charges were baseless—the Latin lines Milton supposedly stole had, in fact, been added to Masenius's original by Lauder—which was demonstrated by John Douglas in his 1750 pamphlet Milton Vindicated from the Charge of Plagiarism Brought Against Him by Mr. Lauder. But Douglas went on to say, in effect, even if the charges were true, it doesn't matter.

I'm not trying to excuse the perpetrators, be they Hatto, her producer-husband, record executives, or some combination of the three. Plagiarism is, to this connoisseur, a particularly poor form of hoaxing, marked by laziness and paucity of imagination. But one wonders if there was more driving the Hatto deception than mere pecuniary gain. It's interesting to note that the first Western composer to sign his name to his work was doing so to prop up a fraud. Ademar of Charbannes was an 11th-century French monk who, determined to prove that his countryman Martial was one of the original apostles of Jesus, fabricated a Vita of Martial, purportedly by his bishoprical successor, Aurelian. Ademar's Apostolic Mass was written to commemorate the planned recognition of Martial's promoted status, but the event was a failure, sabotaged by Ademar's more famous monastical contemporary, Benedict, who regarded the Martial hagiography as nonsense; Ademar tried to appeal to the pope, but was denied the chance. But he had his revenge: forging letters that made it appear that the pope had indeed heard Ademar's case and sided with him, he slipped the documents into a library where he knew no one would see them for several generations. Discovered after his death, the accounts were accepted as authentic, a false history that wasn't unraveled until the 20th century.

Was the Hatto plagiarism something similar? By appropriating the performances of others, was she trying to create an alternate reality, one in which her art triumphed over the vicissitudes of life rather than falling victim to them? It's certainly a more poetic notion. The cynical side of me doubts that the motives were anywhere near that high-minded; but the artistic side of me wants to believe it, that the fraud was, in its own warped way, a type of performance.

Now I have a fondness for well-executed or particularly brazen hoaxes and forgeries, which I've touched on before. What's interesting to me about this one is that although the words fraud, fake, and hoax have been bandied about quite a bit, as far as I can tell, in the initial reports, only Alan Riding's write-up in the New York Times (which Jerry at Sequenza21 wittily purloined) calls the situation what it is: plagiarism. Most forgeries involve taking your own work and passing it off as somebody else's, usually somebody more famous than you. This, if the allegations pan out, is just the opposite: taking someone else's work and passing it off as your own.

I'm not surprised that the hoax went undetected for so long. I like to think that I have reasonably savvy ears, but I would doubt my own ability to hear the deception, unless I was specifically listening for it—and who listens to music that way? (To their credit, some people were suspicious from the first.) What's really intriguing is that no one else (to my knowledge, at least) has tried this before. It would seem to me that classical music recording would provide great opportunities for plagiarism. Why? Because the logistics of performance are pretty close to plagiarism already. Even though there's no attempt at deception, and there's full attribution, a pianist playing the Transcendental Etudes is using notes, rhythms, and dynamics set down by Liszt—and, at least textually, nothing else. Any two performances of the same piece are going to be largely the same. Of course, the artistry lies in the slight differences; but what the individual performer brings to the table is a historical anomaly, something that has persisted in music long after the notion of plagiarism erased it from other intellectual pursuits.

In 1747, the English poet John Milton was accused by one William Lauder of plagiarising much of Paradise Lost from a 1654 Latin poem by Jacobus Masenius. The charges were baseless—the Latin lines Milton supposedly stole had, in fact, been added to Masenius's original by Lauder—which was demonstrated by John Douglas in his 1750 pamphlet Milton Vindicated from the Charge of Plagiarism Brought Against Him by Mr. Lauder. But Douglas went on to say, in effect, even if the charges were true, it doesn't matter.

A great Genius looks upon himself as having a Right to convert to his own Use, and in order to furnish out a more perfect Entertainment, whatever has been already prepared and made ready. But he exercises this Right in such a Manner as to convince every one, that his having Recourse to it is not the Effect of Sterility of his Fancy, but to the Solidity of his Judgement. He borrows only to shew his own Talents in heightening, refining and polishing all that is furnished him by others, and thereby secures his Character as a fine Writer, from being confounded with that of the Dull Copyer.Replace "writer" with "performer," and that's as good a description of musical artistry as I've ever read. Composers, too, at least at this time: George Buelow, who quotes Douglas in his article "Originality, Genius, Plagiarism in English Criticism of the Eighteenth Century," goes on to write, "One can only speculate if the greatest composer in England at this time, George Frederic Handel, might have read Douglas' defense of Milton. For he would have surely nodded in agreement, even though a half century later he too would be accused of plagiarism for having followed much the same principles of imitation in his music." The virtues of such imitation have long been interred under modern ideas of originality and intellectual property, but their ghosts still haunt classical performance.

I'm not trying to excuse the perpetrators, be they Hatto, her producer-husband, record executives, or some combination of the three. Plagiarism is, to this connoisseur, a particularly poor form of hoaxing, marked by laziness and paucity of imagination. But one wonders if there was more driving the Hatto deception than mere pecuniary gain. It's interesting to note that the first Western composer to sign his name to his work was doing so to prop up a fraud. Ademar of Charbannes was an 11th-century French monk who, determined to prove that his countryman Martial was one of the original apostles of Jesus, fabricated a Vita of Martial, purportedly by his bishoprical successor, Aurelian. Ademar's Apostolic Mass was written to commemorate the planned recognition of Martial's promoted status, but the event was a failure, sabotaged by Ademar's more famous monastical contemporary, Benedict, who regarded the Martial hagiography as nonsense; Ademar tried to appeal to the pope, but was denied the chance. But he had his revenge: forging letters that made it appear that the pope had indeed heard Ademar's case and sided with him, he slipped the documents into a library where he knew no one would see them for several generations. Discovered after his death, the accounts were accepted as authentic, a false history that wasn't unraveled until the 20th century.

Was the Hatto plagiarism something similar? By appropriating the performances of others, was she trying to create an alternate reality, one in which her art triumphed over the vicissitudes of life rather than falling victim to them? It's certainly a more poetic notion. The cynical side of me doubts that the motives were anywhere near that high-minded; but the artistic side of me wants to believe it, that the fraud was, in its own warped way, a type of performance.

February 16, 2007

Square-cut or pear-shaped, these rocks don't lose their shape

Stay with me on this one. There's this company called LifeGem (based in Elk Grove Village, Illinois—if you're from Illinois, and you've ever been to Elk Grove Village, this will make increasing sense as you read on) and what they do is take someone's DNA, extract the carbon from it, and use it to make an artificial diamond. It's kind of like that urn of ashes on the mantel that's all that remains of your late Aunt Gladys, except in a form that can be mounted in a Tiffany setting. (Now I'm wondering if I could have my DNA coverted into industrial diamonds, and be permanently memorialized on the tip of a high-end drill bit for Arctic ice cores. But I digress.)

Well, as a publicity stunt, they're making three diamonds from DNA extracted from Beethoven's hair. The diamonds will be exhibited at various (as yet unannounced) "museums and opera houses" around the world, and then be auctioned off. Mount it on a ring, and maybe you'll end up starring in your own real-life remake of The Beast With Five Fingers! The hair is being donated by John Reznikoff, who, according to their website, "holds the Guinness World Record for the largest and most valuable collection of celebrity hair"—which, as of now, is the new "Career Objectives" bullet point on my résumé.

Yep, a diamond made out of Beethoven's hair. Take that, Communism!

(Via Marginal Revolution.)

Well, as a publicity stunt, they're making three diamonds from DNA extracted from Beethoven's hair. The diamonds will be exhibited at various (as yet unannounced) "museums and opera houses" around the world, and then be auctioned off. Mount it on a ring, and maybe you'll end up starring in your own real-life remake of The Beast With Five Fingers! The hair is being donated by John Reznikoff, who, according to their website, "holds the Guinness World Record for the largest and most valuable collection of celebrity hair"—which, as of now, is the new "Career Objectives" bullet point on my résumé.

Yep, a diamond made out of Beethoven's hair. Take that, Communism!

(Via Marginal Revolution.)

Sticks and Bricks (off-topic Friday)

In the wake of a fairly stupid list of 150 favorite American buildings that the AIA perpetrated (idiotic example: Louis Sullivan just barely sneaks in at 145, ranked behind, among others, the Bellagio Hotel and two Apple stores), Tyler Green at Modern Art Notes has encouraged everyone to post their own five choices. I seriously considered becoming an architect at one time, and, as my lovely wife can attest to, I am a certifiable nut on the subject, so I have opinions to spare. To keep things honest, I only picked buildings that I've personally been to (which explains the high concentration around Chicago and Boston), and I limited individual architects to one slot each. ("Sticks and bricks," by the way, was the appellation given to the Tudor revival style by my far more knowledgeable classmates in Keith Morgan's 19th-Century American Architecture class at BU, and I still use it.)

Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company building, Chicago. Louis Sullivan, 1903.

Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company building, Chicago. Louis Sullivan, 1903.

The coolest building in the universe. Here's why: there's the ridiculously intricate wrought-iron work at street level, which always gets a lot of attention. There's also somewhat less intricate decoration around the upper windows. And those windows are placed in a regular grid on the façade. So if you stand right next to the building, as your gaze travels from the wrought-iron to the decoration on the first couple of rows of windows to the upper stories receding in perspective, the amount of decorative detail reaching your eye stays constant. Sullivan was building fractals before anyone knew what a fractal was. Breathtaking. (Really, any Sullivan building would merit this list.)

Fairstead (Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site), Brookline, Mass. F.L. Olmsted (landscape), 1883-.

Fairstead (Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site), Brookline, Mass. F.L. Olmsted (landscape), 1883-.

Again, any Olmsted project could have served (I don't care that they're not buildings, his work is better than 99% of the architecture out there, so keep your semantics to yourself), but I'll go with the grounds around the rambling old farmhouse that was his home and studio for the latter part of his life. In a lot of ways, it's the ultimate Olmsted project, because at first, it doesn't seem like he's really done much of anything, and then you remember that you're looking at a one-acre residential plot in a Bostonian suburb, and you realize that he's done everything, every tree, every shrub, every roll in the lawn, and it all flows together like a dream.

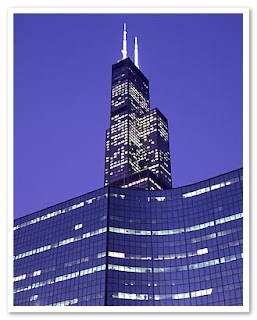

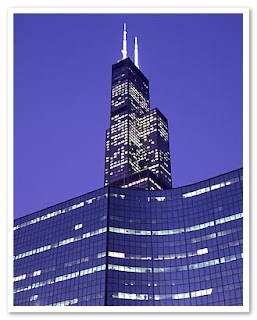

Sears Tower, Chicago. Bruce Graham, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, 1973.

Sears Tower, Chicago. Bruce Graham, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, 1973.

I didn't really appreciate the Sears Tower while I lived in Chicago. It was only after I moved away and started flying into Chicago that I finally got it. Seeing the thing from a plane window, surrounded by other buildings, the staggered square tubes seem to break through the cityscape like columns of granite. It's a great effect: a mountain peak rising out of a nominally flat landscape. Maybe the International style was less about not emulating biological organicism and more about giving geology a little respect. (Photo by our good friend Mark Meyer.)

MIT Chapel, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Eero Saarinen, 1955.

MIT Chapel, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Eero Saarinen, 1955.

Class of 1959 Chapel, Harvard Business School, Boston. Moshe Safdie, 1992.

So there's these two academic, non-denominational chapels, and they're both kinda small and intimate, and they're both circular, and they both have significant water elements (moat at MIT, interior koi pond at HBS), and they're both done in a modern style that nevertheless includes intriguing, idiosyncratic personal details. Lucky for Safdie he's so good, otherwise this would have plagiarism written all over it. Really, though, it's the differences that make each building: Safdie builds around a prismatic skylight that renders everything reflective and cool, Saarinen encases his geometric space in nubbly, irregular brickwork that's human and warm. News you can use: both spaces make terrific untraditional chamber music venues.

Music Box Theater, Chicago. Louis A. Simon, 1929.

Music Box Theater, Chicago. Louis A. Simon, 1929.

The plush velvet seating, the plaster faux-Venetian-palazzo details, the clouds painted on the vaulted ceiling, complete with electric blinking stars—you begin to know why movies were such a big deal back in the day. Think of it as a sublime pop version of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and you start to sense some of the magic. I remember seeing both Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse and Howard Hawks's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes here during my DePaul days, and it was the perfect venue for both. Neat trick.

Honorable Mentions (any of which might have made the top five on a different day): Tribune Tower, Chicago (Howells & Hood, 1925; my wife's favorite building—detail at left); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Willard T. Sears, 1923); Stata Center, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. (Frank Gehry, 2004); The Frick Collection, New York (Thomas Hastings, 1914); Mount Rushmore Visitors' Center, South Dakota (the old one, by Harold Spitznagel & Associates, 1957-63; demolished in 1994); Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, Lenox, Mass. (William Rawn Associates, 1994); and probably more that I'm forgetting.

Honorable Mentions (any of which might have made the top five on a different day): Tribune Tower, Chicago (Howells & Hood, 1925; my wife's favorite building—detail at left); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Willard T. Sears, 1923); Stata Center, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. (Frank Gehry, 2004); The Frick Collection, New York (Thomas Hastings, 1914); Mount Rushmore Visitors' Center, South Dakota (the old one, by Harold Spitznagel & Associates, 1957-63; demolished in 1994); Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, Lenox, Mass. (William Rawn Associates, 1994); and probably more that I'm forgetting.

Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company building, Chicago. Louis Sullivan, 1903.

Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company building, Chicago. Louis Sullivan, 1903.The coolest building in the universe. Here's why: there's the ridiculously intricate wrought-iron work at street level, which always gets a lot of attention. There's also somewhat less intricate decoration around the upper windows. And those windows are placed in a regular grid on the façade. So if you stand right next to the building, as your gaze travels from the wrought-iron to the decoration on the first couple of rows of windows to the upper stories receding in perspective, the amount of decorative detail reaching your eye stays constant. Sullivan was building fractals before anyone knew what a fractal was. Breathtaking. (Really, any Sullivan building would merit this list.)

Fairstead (Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site), Brookline, Mass. F.L. Olmsted (landscape), 1883-.

Fairstead (Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site), Brookline, Mass. F.L. Olmsted (landscape), 1883-.Again, any Olmsted project could have served (I don't care that they're not buildings, his work is better than 99% of the architecture out there, so keep your semantics to yourself), but I'll go with the grounds around the rambling old farmhouse that was his home and studio for the latter part of his life. In a lot of ways, it's the ultimate Olmsted project, because at first, it doesn't seem like he's really done much of anything, and then you remember that you're looking at a one-acre residential plot in a Bostonian suburb, and you realize that he's done everything, every tree, every shrub, every roll in the lawn, and it all flows together like a dream.

Sears Tower, Chicago. Bruce Graham, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, 1973.

Sears Tower, Chicago. Bruce Graham, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, 1973.I didn't really appreciate the Sears Tower while I lived in Chicago. It was only after I moved away and started flying into Chicago that I finally got it. Seeing the thing from a plane window, surrounded by other buildings, the staggered square tubes seem to break through the cityscape like columns of granite. It's a great effect: a mountain peak rising out of a nominally flat landscape. Maybe the International style was less about not emulating biological organicism and more about giving geology a little respect. (Photo by our good friend Mark Meyer.)

MIT Chapel, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Eero Saarinen, 1955.

MIT Chapel, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. Eero Saarinen, 1955.Class of 1959 Chapel, Harvard Business School, Boston. Moshe Safdie, 1992.

So there's these two academic, non-denominational chapels, and they're both kinda small and intimate, and they're both circular, and they both have significant water elements (moat at MIT, interior koi pond at HBS), and they're both done in a modern style that nevertheless includes intriguing, idiosyncratic personal details. Lucky for Safdie he's so good, otherwise this would have plagiarism written all over it. Really, though, it's the differences that make each building: Safdie builds around a prismatic skylight that renders everything reflective and cool, Saarinen encases his geometric space in nubbly, irregular brickwork that's human and warm. News you can use: both spaces make terrific untraditional chamber music venues.

Music Box Theater, Chicago. Louis A. Simon, 1929.

Music Box Theater, Chicago. Louis A. Simon, 1929.The plush velvet seating, the plaster faux-Venetian-palazzo details, the clouds painted on the vaulted ceiling, complete with electric blinking stars—you begin to know why movies were such a big deal back in the day. Think of it as a sublime pop version of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and you start to sense some of the magic. I remember seeing both Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse and Howard Hawks's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes here during my DePaul days, and it was the perfect venue for both. Neat trick.

Honorable Mentions (any of which might have made the top five on a different day): Tribune Tower, Chicago (Howells & Hood, 1925; my wife's favorite building—detail at left); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Willard T. Sears, 1923); Stata Center, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. (Frank Gehry, 2004); The Frick Collection, New York (Thomas Hastings, 1914); Mount Rushmore Visitors' Center, South Dakota (the old one, by Harold Spitznagel & Associates, 1957-63; demolished in 1994); Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, Lenox, Mass. (William Rawn Associates, 1994); and probably more that I'm forgetting.

Honorable Mentions (any of which might have made the top five on a different day): Tribune Tower, Chicago (Howells & Hood, 1925; my wife's favorite building—detail at left); Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (Willard T. Sears, 1923); Stata Center, MIT, Cambridge, Mass. (Frank Gehry, 2004); The Frick Collection, New York (Thomas Hastings, 1914); Mount Rushmore Visitors' Center, South Dakota (the old one, by Harold Spitznagel & Associates, 1957-63; demolished in 1994); Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, Lenox, Mass. (William Rawn Associates, 1994); and probably more that I'm forgetting.

February 15, 2007

Variations (3): Certain rat, dans une cuisine établi

This study reveals that the ultrasonic vocalizations of the mouse have the characteristics of song. Qualitatively, this is apparent directly from playback of pitch-shifted audio recordings; we have also provided quantitative evidence for the usage of distinct syllable types arranged in nonrandom, repeated temporal sequences. These songs satisfy Broughton's sensu stricto definition of song, as well as many aspects of his sensu strictissimo.... While courtship songs are common among birds, insects, and frogs, song has only rarely been documented in mammals, and to our knowledge only in humans, whales, and bats. However, some rodent species display a variety of calls and at least one other, the rat Dactylomys dactylilnus, utters long sequences of vocalizations that contain some syllabic diversity.—Timothy E. Holy and Zhongsheng Guo,

"Ultrasonic Songs of Male Mice,"

PLoS Biology, December 2005

If our present society should disintegrate—and who dare prophesy that it won’t?—this old-fashioned and démodé figure will become clearer: the Bohemian, the outsider, the parasite, the rat—one of those figures which have at present no function either in a warring or a peaceful world. It may not be dignified to be a rat, but many of the ships are sinking, which is not dignified either—the officials did not build them properly. Myself, I would sooner be a swimming rat than a sinking ship—at all events I can look around me for a little longer—and I remember how one of us, a rat with particularly bright eyes called Shelley, squeaked out, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” before he vanished into the waters of the Mediterranean.—E. M. Forster, “Art for Art’s Sake” (1949),

reprinted in Two Cheers for Democracy

February 14, 2007

Omnia vincit amor

One of the most common slams against modernism is that it's no good for love songs. I think that's nonsense, as long as your conception of "love song" ranges beyond trite ditties of the "June-moon-spoon" variety. In honor of Valentine's Day, here's a gorgeous piece I found this week. The late Paul Cooper's Love Songs and Dances was written in 1987, and was dedicated to Ross Lee Finney and his wife. This is grown-up love, rich, deep, sometimes maddening, sometimes magical, always surprising, and sublime—that last movement positively glows. Listen to it here. (Here's some nice tributes to Cooper.)

One of the most common slams against modernism is that it's no good for love songs. I think that's nonsense, as long as your conception of "love song" ranges beyond trite ditties of the "June-moon-spoon" variety. In honor of Valentine's Day, here's a gorgeous piece I found this week. The late Paul Cooper's Love Songs and Dances was written in 1987, and was dedicated to Ross Lee Finney and his wife. This is grown-up love, rich, deep, sometimes maddening, sometimes magical, always surprising, and sublime—that last movement positively glows. Listen to it here. (Here's some nice tributes to Cooper.)Painting by Benjamin West.

February 13, 2007

Dramatic license

Reviewing the Borromeo Quartet.

Boston Globe, February 13, 2007.

For some reason I thought this wouldn't run until tomorrow. When it rains, it pours.

Boston Globe, February 13, 2007.

For some reason I thought this wouldn't run until tomorrow. When it rains, it pours.

Labels:

Globe Articles

Nature/nurture

Reviewing Garrick Ohlsson.

Boston Globe, February 13, 2007.

Boston Globe, February 13, 2007.

Labels:

Globe Articles

February 12, 2007

Safety Last

Hey, one of our favorite people here at Soho the Dog HQ picked up a couple of Grammys last light. Osvaldo Golijov's opera Ainadamar won for Best Opera Recording and Best Classical Contemporary Composition. ¡Felicitaciones! As for the rest of the Grammys, suffice to say that Bon Jovi won for a country song. And Lenny Gomulka was robbed. Robbed.

Here's some good timing: Opera Boston announced this week that they'll present Ainadamar next season, along with Handel's Semele and Verdi's Ernani. Pretty interesting season, no? Also this week, the other opera company in town, Boston Lyric Opera, announced their upcoming season: La Bohéme, Donizetti's Elixir of Love, and Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio—not so interesting. I mean, I'm a committed Elixir junkie, but if you only get three slots a year, you might want to perhaps survey some repertoire that isn't also being sung by college training programs around town. (BU put on Bohéme not long ago; Boston Conservatory is mounting Elixir this spring.) BLO's general manager was quoted as saying, "Our recent audience survey says that both single-ticket and subscription buyers are saying that they really prefer the top 10 or 20 operas, and lesser-known masterworks by popular composers." Hmmm... you asked your audience what operas they liked, and they failed to mention any pieces they didn't know? What a shocker. You know, if your idea of management is giving the customer what they already know they want, there's a bright future for you in retail fast-food sales.

Here's a fun stat: with Ainadamar, Opera Boston will have presented more works by living composers since 2003 than BLO has in their entire history (going back 30 years). Can you guess who'll be the beneficiary of my pocket money?

Here's some good timing: Opera Boston announced this week that they'll present Ainadamar next season, along with Handel's Semele and Verdi's Ernani. Pretty interesting season, no? Also this week, the other opera company in town, Boston Lyric Opera, announced their upcoming season: La Bohéme, Donizetti's Elixir of Love, and Mozart's Abduction from the Seraglio—not so interesting. I mean, I'm a committed Elixir junkie, but if you only get three slots a year, you might want to perhaps survey some repertoire that isn't also being sung by college training programs around town. (BU put on Bohéme not long ago; Boston Conservatory is mounting Elixir this spring.) BLO's general manager was quoted as saying, "Our recent audience survey says that both single-ticket and subscription buyers are saying that they really prefer the top 10 or 20 operas, and lesser-known masterworks by popular composers." Hmmm... you asked your audience what operas they liked, and they failed to mention any pieces they didn't know? What a shocker. You know, if your idea of management is giving the customer what they already know they want, there's a bright future for you in retail fast-food sales.

Here's a fun stat: with Ainadamar, Opera Boston will have presented more works by living composers since 2003 than BLO has in their entire history (going back 30 years). Can you guess who'll be the beneficiary of my pocket money?

February 09, 2007

Dogs are not allowed in library

I've been awfully busy today, so in lieu of a proper post, I set critic-at-large Moe loose at the Library of Congress. It's not like he's been doing that much reviewing lately—time to step up and start earning that steady stream of tennis balls and freeze-dried liver treats! (There he is at right, resting after his labors.) Anyway, after sniffing around for a couple of hours, here's what he came up with:

I've been awfully busy today, so in lieu of a proper post, I set critic-at-large Moe loose at the Library of Congress. It's not like he's been doing that much reviewing lately—time to step up and start earning that steady stream of tennis balls and freeze-dried liver treats! (There he is at right, resting after his labors.) Anyway, after sniffing around for a couple of hours, here's what he came up with:"Dogs," a pretty funny old Barbary Coast ditty, as performed by Byron Coffin, Sr. in 1939 (audio recording).

photo by William Gottleib.

"That Mastiff Dog She Bought," comic song by F. E. Galbraith, 1879 (sheet music).

"Mr. Bethel Dog Bit Me," a Bahamian folksong, as performed by Theodore Rolle ("Tea Roll") in 1940 (audio recording).

photographer unknown, 1927.

(In retrospect, I should have guessed this was coming.)

February 08, 2007

Late Show

Live, from 1986, it's Philip Glass and his eponymous ensemble, appearing on a major-network sketch comedy show which shall remain unnamed. Added value: great shots of all the vintage gear, and George Wendt (!) introducing the major operatic composer of our time.

Live, from 1986, it's Philip Glass and his eponymous ensemble, appearing on a major-network sketch comedy show which shall remain unnamed. Added value: great shots of all the vintage gear, and George Wendt (!) introducing the major operatic composer of our time.Philip Glass Ensemble performs Rubric, NYC 1986 (YouTube)

February 07, 2007

All the world's a stage

The word "revolutionary" gets thrown around a lot with reference to new music. But how do you measure just how revolutionary a musical style is? Who's the greater innovator: Debussy or Stravinsky? Is serialism or minimalism a bigger break with the past? Here's a possible criterion: do the critics go through all five Kübler-Ross stages?

The Kübler-Ross model is usually associated with death and the surrounding grief, but Kübler-Ross herself intended it as a representation of how people deal with any catastrophic information. So if an avant-garde vocabulary/technique/philosophy really has the shock of the new, we should see the results greeted with those five little words:

Denial: This isn't music! Anger: I'm insulted that this music is being inflicted on me. Bargaining: Perhaps other people might accept this as music, but please don't let it happen while I'm around. Depression: If this is what passes for music these days, we're in a sorry state indeed. Acceptance: Hey, maybe this stuff isn't so bad after all.

Note that the Kübler-Ross stages don't have to happen in any particular order (although acceptance usually comes last). And some of these could be combined: denial and anger, for example (I'm insulted that you would try and make me think this is music).

So what do the stages look like in the field? Let's try everybody's favorite bugaboo, Arnold Schoenberg.

Denial: Arnold Schoenberg's famous, or notorious, Five Pieces for Orchestra are worse than the reputation that preceded them.... There is not the slightest reason to believe that their squeaks, groans and caterwaulings represent in any way the musical idiom of today or tomorrow or of any future time. (Richard Aldrich, New York Times, November 30, 1921) Anger: The performance of a new string quartet by Arnold Schoenberg must also be mentioned.... [I]n the middle of the last movement people shouted at the top of their voices: 'Stop! Enough! We will not be treated like fools!' And I must confess to my sorrow that I, too, let myself be driven to similar outbursts. (Ludwig Karpath, Signale [Berlin], January 6, 1909) Bargaining: I fear and dislike the music of Arnold Schoenberg... If such music-making is ever to become accepted, then I long for Death the Releaser. (James Huneker, New York Times, January 19, 1913) Depression: How miserable would our descendants be, if this joyless gloomy Schoenberg would ever become the mode of expression of their time! (Hugo Leichtentritt, Signale [Berlin], February 7, 1912) Acceptance: One likes to think that just as the Five Pieces paved the way for Pierrot Lunaire so the Variations are paving the way for a second masterpiece of a similar calibre. Even if this be not the case, the Variations remain among the most outstanding works written since the war and are undoubtedly the most important music Schönberg has written for twenty years. For whereas the post-war piano suites might have been written by any of Schönberg's followers, the Variations could only have been written by the master himself. (Constant Lambert, Music Ho!, 1935)

(The first four from, where else? Nicolas Slonimsky's Lexicon of Musical Invective.) In a similarly teutonic spirit, what about one of Schoenberg's favorites, Brahms?

Denial: What is then nowadays music, harmony, melody, rhythm, meaning, form, when this rigmarole seriously pretends to be regarded as music? If Herr Dr. Johannes Brahms intends to mystify his admirers with this newest work, if he wants to make fun of their brainless veneration, then it is of course something else, and we marvel at Herr Brahms as the greatest bluffer of this century and of all future millenia. (Hugo Wolf, Salonblatt [Vienna], December 5, 1886) Anger: I played over the music of that scoundrel Brahms. What a giftless bastard! It annoys me that this self-inflated mediocrity is hailed as a genius. (Tchaikowsky's diary, October 9, 1886)

...and so forth. I would guess that a scrapbook of Philip Glass reviews would yield five pertinent examples without too much trouble, and a survey of "respectable" reactions to the coming of jazz in the early 1900's would make a fine case study, as well.

I find it hard to believe that I'm the first person to think of this, but a quick web search didn't turn up anything similar. (I did find this article that analyzes Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra as a series of Kübler-Ross stages.) Anyone know if somebody out there has taken this beyond a mere blog post?

The Kübler-Ross model is usually associated with death and the surrounding grief, but Kübler-Ross herself intended it as a representation of how people deal with any catastrophic information. So if an avant-garde vocabulary/technique/philosophy really has the shock of the new, we should see the results greeted with those five little words:

Note that the Kübler-Ross stages don't have to happen in any particular order (although acceptance usually comes last). And some of these could be combined: denial and anger, for example (I'm insulted that you would try and make me think this is music).

So what do the stages look like in the field? Let's try everybody's favorite bugaboo, Arnold Schoenberg.

(The first four from, where else? Nicolas Slonimsky's Lexicon of Musical Invective.) In a similarly teutonic spirit, what about one of Schoenberg's favorites, Brahms?

...and so forth. I would guess that a scrapbook of Philip Glass reviews would yield five pertinent examples without too much trouble, and a survey of "respectable" reactions to the coming of jazz in the early 1900's would make a fine case study, as well.

I find it hard to believe that I'm the first person to think of this, but a quick web search didn't turn up anything similar. (I did find this article that analyzes Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra as a series of Kübler-Ross stages.) Anyone know if somebody out there has taken this beyond a mere blog post?

February 06, 2007

Learning the blues

Over at "Dial M" last week, Phil issued his iPod challenge, while Jonathan offered some career advice. Jonathan said that popular music, in his opinion, wasn't necessarily the best musicological wall to toss your prospectively employed cap over, but of course, popular music was what turned up in spades on the hard drives of those to took up Phil's dare. (This led to its own Brundlefly-like combination meme.)

In the spirit of things, here's a little souvenir of the initial incursion of pop into the ivory tower. The first jazz theory class, ever, wasn't offered in the United States—it was at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, Germany, taught by a young Hungarian composer named Mátyás Seiber. Seiber started the class in 1928, and by 1931, had achieved enough notoriety that he and the Hoch Conservatory jazz band were invited to perform for German radio—and you can listen to their performance of Peter Packay's "Oh My" courtesy of the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv. (Real Player only, which is a mild annoyance.) How do they do? Not bad at all—except for a few ragged syncopations, they could easily pass for an American or British "hot" band of the period.

The Nazis, pretty predictably, didn't take kindly to Seiber's class, and, upon its cancellation in 1933, Seiber emigrated to London, where he kept busy as a teacher and composer, appropriately working in a wide variety of styles and genres, from avant-garde to pop. (His cantata on Joyce's Ulysses, which I remember perusing the score of, is an unjustly neglected gem.) He died in a car crash in 1960; Ligeti dedicated the score of Atmosphères to his memory, which gives you some indication of the breadth of his career and influence.

In the spirit of things, here's a little souvenir of the initial incursion of pop into the ivory tower. The first jazz theory class, ever, wasn't offered in the United States—it was at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, Germany, taught by a young Hungarian composer named Mátyás Seiber. Seiber started the class in 1928, and by 1931, had achieved enough notoriety that he and the Hoch Conservatory jazz band were invited to perform for German radio—and you can listen to their performance of Peter Packay's "Oh My" courtesy of the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv. (Real Player only, which is a mild annoyance.) How do they do? Not bad at all—except for a few ragged syncopations, they could easily pass for an American or British "hot" band of the period.

The Nazis, pretty predictably, didn't take kindly to Seiber's class, and, upon its cancellation in 1933, Seiber emigrated to London, where he kept busy as a teacher and composer, appropriately working in a wide variety of styles and genres, from avant-garde to pop. (His cantata on Joyce's Ulysses, which I remember perusing the score of, is an unjustly neglected gem.) He died in a car crash in 1960; Ligeti dedicated the score of Atmosphères to his memory, which gives you some indication of the breadth of his career and influence.

February 05, 2007

Reading Session